There are all kinds of arguments about book-to-film adaptations, including complaints that commentary on the source material has no place in a film review. Putting aside the anti-intellectual strain in much of the discourse, the film differs from the book and must be judged on its own terms. Changes to the original story will infuriate purists, but “faithful” adaptations can be so “respectful” they die onscreen. However, when it comes to critiquing a film adaptation, one thing is pretty clear from years of doing this: when the film doesn’t work, the problem often lies in the choices made when adapting the source material.

Enter “The Thing with Feathers,” the new film based on Max Porter’s celebrated 2015 debut novel Grief is the Thing with Feathers. Directed by Dylan Southern, it stars Benedict Cumberbatch as a widower, drowning in grief, attempting to parent two young sons alone, all while a giant crow stalks the family. The book is an unnerving evocation of grief. The crow infiltrates the house, hangs out with the boys, and whispers provoking things to the dad. Is the crow there to heal the family? Father, sons, and crow split the narration. Porter said in an interview, “The experience of the boys in the novel is based on my dad dying when I was six.” (The book’s title is taken from Emily Dickinson’s famous poem “‘Hope is the thing with feathers”.)

In 2019, the book was adapted into a play, directed and adapted by Enda Walsh, starring Cillian Murphy in its premiere production in London. Walsh is a gifted adapter, as evidenced by his screenplays for both “Small Things Like These” and “Die My Love”. Southern didn’t use Walsh’s adaptation for the film. He adapted the book himself, making a couple of key changes and choosing to approach the material through a horror-genre lens. Southern wields the tropes in a stylistically over-determined way–jump-scares and all–which cheapens the delicate and poetic narrative.

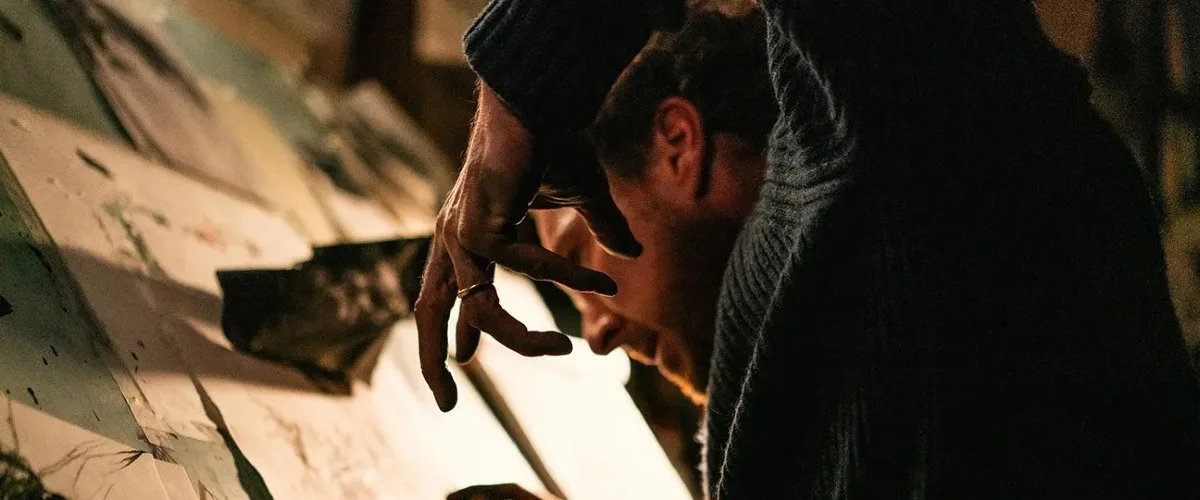

Cumberbatch and the two children playing the sons, siblings Richard and Henry Boxall, all give authentic, touching performances. Dad is a graphic novelist (though he doesn’t like that term), and his new manuscript is due soon. It’s hard to settle down to creative work, though, when a gigantic crow looms over your shoulder, hissing comments (the crow is voiced by David Thewlis). Dad falls apart, becoming more and more crow-like. The kids try to avoid the catastrophe befalling their surviving parent.

Cinematographer Ben Fordesman uses pitch-black shadows so dark they become voids on the screen. When the human-sized crow appears, it’s hard to tell where the shadow ends and the crow begins. (Fordesman shot the excellent “Saint Maud,” as well as “Love Lies Bleeding” and this year’s “Anemone”.)

The crow (designed by Nicola Hicks) has a long, curved neck and an almost comical silhouette. Its claws stick out like spikes, reminiscent of the Babadook, a perhaps deliberate but unfortunate comparison. The two films share much in common, but “The Babadook” succeeds where “The Thing with Feathers” does not. “The Babadook” was a terrifying film in its surface details while also being a brilliant metaphor for living with mental illness. Why the Babadook arrived at the house and why it won’t leave adds to the film’s symbolic weight. In “The Thing with Feathers,” it’s not clear why a crow chooses to haunt the family. Why not a cat/dog/moose? Why, specifically, a crow? The dad’s book isn’t about crows. The crow, then, is random.

Here is where I need to talk about the source material. The “why” of the crow is not only explained in Porter’s book but is the book’s whole organizing principle. In the book, the father is not a graphic novelist, but a scholar working on a book about Ted Hughes’ 1970 poetry collection Crow: From the Life and Songs of the Crow. Even if you don’t know the significance of this collection (and it was hugely significant), Porter’s book makes you curious. In 1962 Ted Hughes and his wife, American poet Sylvia Plath, separated (he left her for another woman, a poet named Assia Wevill). Plath committed suicide the following year (the two babies she and Hughes had together were asleep upstairs). The poems in Crow were all written in the mid-60s, a time of grief and renewal for Hughes. (Horrifically, in 1969, Wevill committed suicide, via the same method Plath used, and killed the daughter she had with Hughes.) The following year, Hughes released Crow.

This is essential context for a film about a man with two children grieving his dead wife, yes? A huge crow then stalks a man spending all of his time reading Hughes’ crow poems. Removing this connection obliterates not just the story’s structure but the story’s deeper meaning. Without it, the crow is a random oddity waddling through the house, looking vaguely like the Babadook. Making the father a graphic novelist was perhaps a way to add some visual interest. It’s undeniably challenging to make an academic scholar interesting to audiences (although Cillian Murphy managed to do it in the stage production).

In the book, the crow explains himself (and quotes Ted Hughes, his creator, in the process):

“I was friend, excuse, deus ex machina, joke, symptom, figment, spectre, crutch, toy, phantom, gag, analyst and babysitter. I was, after all, ‘the central bird … at every extreme’.”

Removing the Ted Hughes connection from “the central bird” cuts off the wellspring from its source.