Three women, three times, three places. Three suicide attempts, two successful. All linked in a way by a novel. In Sussex in 1941, the novelist Virginia Woolf fills the pockets of her coat with rocks and walks into a river to drown. In Los Angeles in 1951, Laura Brown fills her purse with pills and checks into a hotel to kill herself. In New York in 2001, Clarissa Vaughan watches as the man she was once married to decides whether to let himself fall out of a window, or not.

The novel is Mrs. Dalloway, written by Woolf in 1925. It takes place in a day during which a woman has breakfast, buys flowers and prepares to throw a party. The first story in “The Hours” shows Virginia writing about the woman, the second shows Laura reading the book, the third shows Clarissa buying flowers after having said one of the famous lines of the book. All three stories in “The Hours” begin with breakfast, involve preparations for parties, end in sadness. Two of the characters in the second story appear again in the third, but the stories do not flow one from another. Instead, they all revolve around the fictional character of Mrs. Dalloway, who presents a brave face to the world but is alone, utterly alone, within herself, and locked away from the romance she desires.

“The Hours,” directed by Stephen Daldry and based on the Pulitzer Prize-winning novel by Michael Cunningham, doesn’t try to force these three stories to parallel one another. It’s more like a meditation on separate episodes linked by a certain sensibility–that of Woolf, a great novelist who wrote a little book titled A Room of One’s Own that in some ways initiated modern feminism. Her observation was that throughout history women did not have a room of their own, but were on call throughout a house occupied by their husbands and families. Austen wrote her novels, Woolf observed, in a corner of a room where all the other family activities were also taking place.

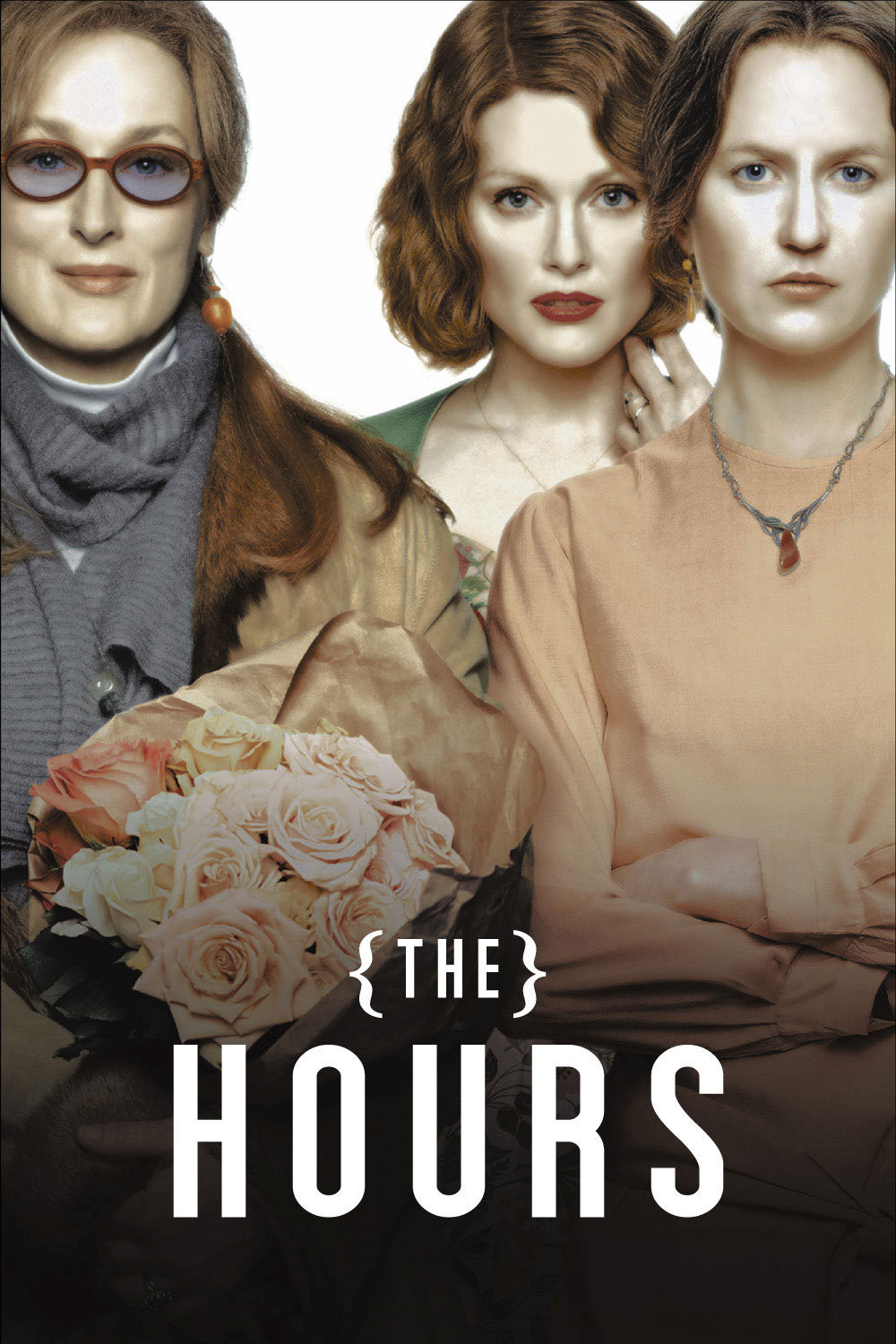

In “The Hours,” Woolf (Nicole Kidman) has a room of her own, and the understanding of her husband, Leonard (Stephen Dillane), a publisher. Laura (Julianne Moore), whom we meet in the 1950s, is a typical suburban housewife with a loving and dependable husband (John C. Reilly) she does not love, and a son who might as well be from outer space. A surprising kiss midway through her story suggests she might have been happier living as a lesbian. Clarissa (Meryl Streep), who we meet in the present, is living as a lesbian; she and her partner (Allison Janney) are raising a daughter (Claire Danes) and caring for their friend Richard (Ed Harris), now dying of AIDs. (We may know, although the movie doesn’t make a point of it, that Virginia Woolf was bisexual.) If this progression of the three stories shows anything, it demonstrates that personal freedom expanded greatly during the decades involved, but human responsibilities and guilts remained the governing facts of life. It also shows that suicides come in different ways for different reasons. Woolf’s suicide comes during a time of clarity and sanity in her struggle with mental illness; she leaves a note for Leonard saying that she feels the madness coming on again, and wants to spare him that, out of her love for him. Laura attempts suicide out of despair; she cannot abide her life, and sees no way out of it, and the love and gratitude of her husband is simply a goad. Richard, the Ed Harris character, is in the last painful stages of dying, and so his suicide takes on still another coloration.

And yet–well, the movie isn’t about three approaches to sexuality, or three approaches to suicide. It may be about three versions of Mrs. Dalloway, who in the Woolf novel is outwardly a perfect hostess, the wife of a politician, but who contains other selves within, and earlier may have had lovers of both sexes. It would be possible to find parallels between Mrs. Dalloway and “The Hours”–the Ed Harris character might be a victim in the same sense as the shell-shocked veteran in the novel–but that kind of list-making belongs in term papers. For a movie audience, “The Hours” doesn’t connect in a neat way, but introduces characters who illuminate mysteries of sex, duty and love.

I mentioned that two of the characters in the second story appear again in the third. I will not reveal how that happens, but the fact that it happens creates an emotional vortex at the end of the film, in which we see that lives without love are devastated. Virginia and Leonard Woolf loved each other, and Clarissa treasures both of her lovers. But for the two in the movie who do not or cannot love, the price is devastating.