Philip Thompson’s “Living Reality” takes viewers on a strange journey through a terrible TV sitcom, where characters recite lines that hack writers think TV characters should say, and a video collage of real moments that contrasts with everything else. When you step back and think about it, what the main character experiences is not dissimilar to the imagined conversations we feel we could be having if we could only be witty and quick-thinking in the moment, and the awkward, inarticulate conversations we have in real life.

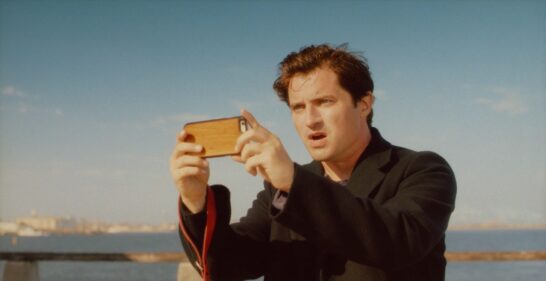

There’s more to the film than that, but “Living Reality” starts us off in a cringey place where four cookie-cutter single, white friends joke about the dates they’re going on while plotting insipid hijinks in hopes of bedding twins. The one person in the room who isn’t saying anything is Theo (director Thompson). Theo tries to talk for real, but his speech and mannerisms seem alien to the other four stars of the show, who only know how to speak the language of a single-season sitcom. Theo has no choice but to excuse himself and go home.

We leave the confines of the sitcom and go with him to his dilapidated studio apartment, where no laughter is heard. He turns on his TV and falls asleep while watching a seemingly random collection of home videos, featuring people in more intimate and genuine moments of their lives. Theo doesn’t exist within any of these videos, but he probably yearns to be, instead of being trapped in a canned laugh track-fueled, purgatorial existence.

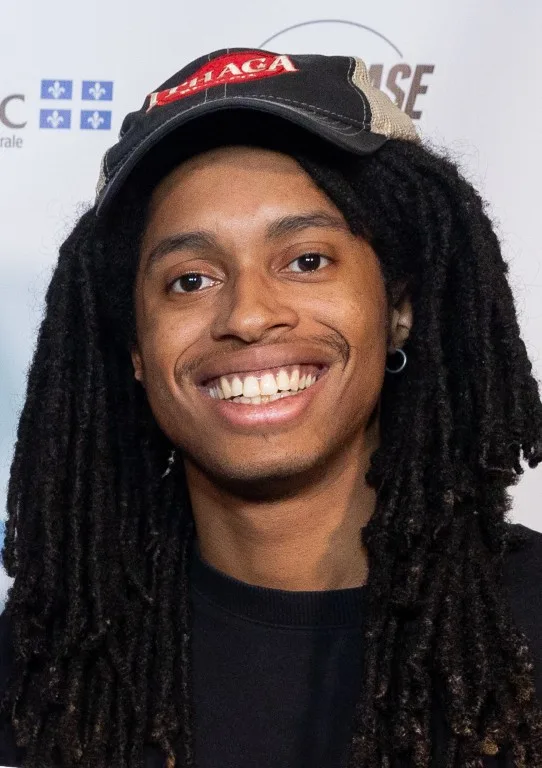

Many will read a lot of racial overtones in the piece, since Theo is the only person of color in the sitcom. There are many ways to look at that, but Thompson never goes out of his way to underline that aspect of the piece or to call attention to it. Even the final line in the film has multiple meanings, but Thompson is smart to let the style—all the styles, actually—speak for itself. We come away from the film wanting to watch it again, rather than feeling like we’ve just been given an obvious message spoon-fed to us.

“Living Reality” turned out to be a much more popular film than I imagined it would be when I programmed it at the Chicago Critics Film Festival last spring. It did not win the Audience Award, but it received many votes as an audience favorite, primarily from viewers in their twenties. The film has a lot to say about the isolating feeling of being constantly bombarded with different types of media that try to dictate people’s behavior. We’ve all grown up with that to some degree, but Thompson’s film mirrors a contemporary landscape that will feel different for every viewer who watches it.

You can watch “Living Reality” here on NoBudge.

Q&A with director and star Philip Thompson

How did this idea come about?

I’m always fascinated by the way movies and TV have such an influence on our society, often in ways we aren’t always aware of. The original conceit came from this image I had of television characters watching us on TV and being directly influenced by our real world, and my mind started racing about how that would reflect back into their fictionalized TV world in strange and sad ways. From there, I started building more personal layers into the idea, drawing from my own life as a black twentysomething in New York. I was interested in the disconnect between the idealized version of life we see on TV and the reality I live in, something I feel is much more depressingly monotonous and uncertain.

I’ve always loved diptych storytelling because it forces audiences to engage critically with the subjects they’re observing, allowing them to compare and contrast two opposing stories and arrive at their own conclusions. So the idea of juxtaposing a familiar sitcom format with something more raw and unscripted felt really exciting, both stylistically and emotionally. I’m drawn to the clash of tones and aesthetics, especially since my main visual inspirations range from classic sitcoms to early 2010s Mumblecore and the Dogme 95 movement. It felt like a chance to combine everything I love into one film, and once that all clicked, we decided to just go for it.

The sitcom elements you came up with seem very real and familiar. Even the VHS style is just right, which is something that’s hard to do well. Was that hard to figure out on a technical level?

Recreating a sitcom certainly came with its own challenges. But also since we had such a clear blueprint, it also made it easy in a lot of ways. Writing the sitcom was straightforward, since the beats and structure are so ingrained from all the shows I grew up obsessing over. We were essentially recreating the thing I’ve loved most since I was a kid. The most difficult part of replicating the sitcom was finding the right laugh track for every joke. One would think it’s as simple as pressing a “laugh” button, but instead you need to find the right laugh to sell every joke. We spent a ridiculous amount of time combing through laugh track libraries and watching the same scenes over and over with different laughs just to get the right one. That’s what slowed down the editing process the most.

As for the VHS look, it was really just a matter of putting the film onto a VHS tape, then re-digitizing it, and making sure it had the right ‘tracking’ level. That gave it the texture and degradation that makes it feel like something you’d find on an old tape upload on YouTube. I guess for me, the whole thing is about trying to imitate very specific memories, capturing that feeling of watching something you loved a long time ago, exactly the way you remember it.

It’s probably pretty obvious, but what actual sitcom(s) inspired the sitcom in your film?

“Friends” and “How I Met Your Mother” were big inspirations, or really just any show that captured that dreamy, idealized version of being a twentysomething in New York City. Those kinds of sitcoms shaped what I thought my adult life was gonna look like. They created this fantasy that I wanted to grow into.

However, in terms of the actual humor, that definitely comes more from the shows I grew up watching as a kid, such as “Drake & Josh” or “Hannah Montana.” I was trying to channel that 90s-2000s sitcom energy, that specific rhythm and tone that made me completely glued to the screen. The goal was to recreate the kind of TV that made me feel like I wasn’t alone, that I had friends, and that I was making a genuine human connection.

When the movie makes that transition to reality, how did you figure out what to explore there? Everything seems spontaneous and/or improvised, and a bit random. How did your approach to directing change for those scenes?

In the original draft of the script, I wanted the “real life” section of the film to mirror something like “How To With John Wilson,” where we just capture the banality of human existence from afar. However, after filming and editing the entirety of the sitcom section, we took a step back and realized that many of the conversations in those early scenes centered on dating, relationships, and navigating one’s twenties in New York City. Because of that, we decided to make the scenes more specifically surrounding people in their 20s in New York, capturing subjects of intimacy, friendships, and the beautiful mundanity of how life feels at that age.

Directing-wise, the shift between the two sections was dramatic. The sitcom portion was highly constructed: we had a built set, a locked script, rigid blocking, and multiple rehearsals. Everything was designed to feel polished and “performed.” But for the “real life” section, we wanted the complete opposite: We wanted it to feel raw, messy, and lived-in.

We cast a lot of non-actors for those scenes, mostly friends of mine who actually live in Brooklyn. I tried to shape the scenes around their real experiences, and whenever I gave them something scripted, it always felt too stiff. It never landed as naturally as when they spoke in their own words, improvised, or just existed on camera. That looseness gave the film an authenticity we couldn’t fake, and it created a really stark, intentional contrast with the constructed world of the sitcom.

Your character resigns himself to this unsatisfying and shallow world of the sitcom. How does that resignation resonate with you? Was that feeling the catalyst for this project in any way?

I think that feeling is how most of us feel about living in the real world. Actually, maybe I won’t speak for everyone. This is how I feel about living in the real world. I don’t always understand its rules or how people behave. What to do and what not to do. But I know I have to comply in order to be seen as a sane member of human society. If you don’t fit in, then they label you as a crazy person. And if you can’t beat ’em, join ’em. So I guess that’s one of the more personal parts about the film, I don’t really know how to fit in or even behave like a regular human being, so I just act like the other people around me. Monkey see, monkey do. It seems to have worked so far.

Originally I ended the film with Theo just stuttering off into a ramble of nothingness. But Theo trying to open up, only to be rejected by his castmates and the artificiality rebelling against the sincerity, made for a more compelling ending. So no, it wasn’t the catalyst. But just a way to end it with a bit more of a period as opposed to an ellipsis.

People also always ask me why the ending feels so unsatisfying, almost as if they expected Theo to go on a rampage and tell everyone off, or kill them all or something. But that’s not how most people behave. Theo will just continue on with his sad life, just trying to fit in with the other people around him, and only finding solace in his television at home when he rots in bed. It’s the most relatable and human way to end it I think. It’s just the way things go. Maybe other people can relate.

What’s next for you?

Right now, I’m focused on making long-form work. I’m currently in pre-production on one feature and writing another that will also be developed. Both projects are thematically in line with Living Reality: They explore television, the power of the images we consume, and how those images shape our understanding of the world. Specifically, they both deal with how race is perceived through the lens of popular American media. So in a way, I’m continuing to unpack the same questions, just on a larger and more layered scale.