On August 21, 2015, three Americans traveling through Europe subdued a terrorist who tried to kill passengers on the Thalys train #9364 bound for Paris. The men were Airman First Class Spencer Stone, Oregon National Guardsman Alek Skarlatos, and college student Anthony Sadler. They’d been friends since childhood. The gunman, a Morrocan named Ayoub El Khazzani, exited a washroom strapped with weapons, wrestled with a couple of would-be heroes, and shot one of them in the neck with a pistol. Stone tackled Khazzani and locked him in a choke hold while being repeatedly sliced with a knife. Stone’s two friends plus Chris Norman, a 62-year-old British businessman living in France, hit Khazzani with their fists and with the butts of firearms that he’d dropped into the struggle until he finally lost consciousness. Then they kept the shooting victim alive until the train was able to stop and let police and emergency medical technicians onboard. For their bravery, Norman, Sadler, Skarlatos, and Stone were made Knights of the Legion of Honour by French president François Hollande, and given awards, parades, and talk show appearances back home.

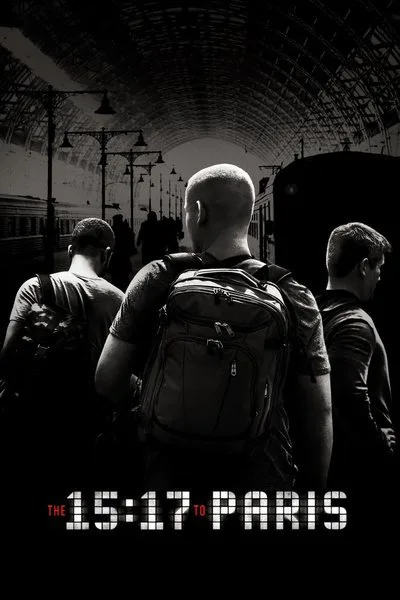

As Hollywood film fodder, this is—or should have been—a slam dunk, even for a director who insisted on having the three Americans play themselves, which is the case here. To call Clint Eastwood‘s “The 15:17 to Paris” a mixed bag would be generous. It packs all the wild action you came to see into a 20-minute stretch near the end, and elsewhere gives us something like a platonic buddy version of Richard Linklater’s “Before” trilogy. This is an audacious choice regardless of whether you’re into it.

Too bad seeing this trio re-enact their European vacation is as absorbing as watching a friend’s video footage of a trip you didn’t go on. As cinematographer Tom Stern’s camera hangs close-but-not-too-close, Sadler, Stone and Skarlatos retrace their steps, traveling from Rome and Venice to Berlin and Amsterdam, cracking jokes about old buildings and sculptures, flirting with attractive women, getting liquored up in a nightclub. You feel like you’re right there alongside them. This is an eerie and astonishing feeling when they’re re-enacting the train incident, but not when they’re ordering food or taking selfies.

There’s a long tradition of real people starring in films about their lives, from Pancho Villa and Jackie Robinson to Muhammad Ali and Howard Stern, and some film cultures, particularly Italy’s Neorealism and Iran’s post-1980s docudramas, have a proud history of extraordinary nonprofessional performances. World War II Medal of Honor winner Audie Murphy went straight into acting with help from a famous admirer, James Cagney, played himself in 1955’s “To Hell and Back,” based on his same-titled memoir, and died 21 years later with 50 screen credits. There haven’t been too many instances where audiences looked at these performances and thought, “Wow, what an incredible actor—a professional wouldn’t have added anything.” But if the nonprofessional seems relatively comfortable onscreen and lets a bit of personality come through, the film can work. And the performance might be likable. Or at least not painful.

I’m relieved to report that not only are these three less than terrible in their big screen debuts, they’re kind of charming, once you decide to make peace with the fact that Eastwood has traded the depth and nuance that a professional can bring for the unpredictable freshness you can only get from casting newcomers. Stone is an unexpectedly striking screen presence: a towering, broad-shouldered, lethal goofball with a comic book henchman’s jawline and a bubbly, impatient manner of speaking. There are moments when his rat-a-tat delivery, practically tripping over his own words, suggests an unholy fusion of Drew Carey and young Gary Busey. I wouldn’t be surprised to see him wind up on a sitcom opposite Tim Allen or Kevin James. The other two seem to have been granted screen time in proportion to their not-terribleness. We get a lot of Stone with Sadler, who’s not a particularly deep actor, to put it mildly, but is disarmingly natural and has a great rapport with his pal. Skarlatos, a handsome but wooden nice guy, is kept mostly offscreen until he joins the others.

But no matter what you think of these men as thespians, their performances are the least of the film’s problems. A good 70% of “The 15:17 to Paris” is inert, its affable nothingness redeemed only by the laid-back charisma of three men who once again find themselves in extraordinary circumstances and have no choice but to rise to the occasion.

The film starts with a flashback to the trio’s childhood, with Jenna Fischer and Judy Greer as Skarlatos and Stone’s mothers, that promises an American Fighting Man Epic in the vein of “Sergeant York” or “Hacksaw Ridge.” But these scenes fall almost entirely flat, with character traits being more described than dramatized. The scene where the moms argue with a snotty administrator who tries to diagnose Stone with ADHD while dissing both women for being single mothers might be the worst five minutes Eastwood has put onscreen, but it has lots of competition here. How Eastwood managed to get worse performances out of the professional actors playing the young heroes than the adults who’d never acted is a mystery that only another director can properly unravel. Ace character actors Tony Hale and Thomas Lennon are wasted as, respectively, the school’s principal and gym coach. Jaleel White is given just one scene to convince us that he’s a great teacher who inspired the boys’ interest in history; it lasts about 60 seconds and ends with him handing them a manila folder full of maps. The moms mention God occasionally, but usually in a stilted way, and their families’ spiritual lives aren’t examined in any detail (though there are a couple of prayers in the film, which is rare for a Hollywood movie).

The screenplay, adapted by Dorothy Blyskal from a book co-written by the trio plus Jeffrey E. Stern, is often painfully awkward and obvious. Earnest discussions of fate and destiny are shoehorned into shallow but generally likeable (and seemingly improvised) scenes of the guys talking to each other, and to people they meet during their journey. A couple of the latter are so odd that they verge on sublime, like the bit when an old man at a bar talks them into going to Amsterdam by recounting the illicit good time he just had there.

But for the most part, “The 15:17 to Paris” is a study in misplaced priorities. While the re-enactment of the incident on the train is superb—Eastwood has always had a flair for staging unfussy yet shockingly brutal screen violence—I’d have happily traded the lead-up hour of marshmallow fluffery for scenes that showed what happened to the guys once they got back to their home country and were treated like gods on earth (though, in fairness, Eastwood might’ve figured he told that story already in “Flags of Our Fathers”). And there are some groaner choices, like Eastwood’s refusal to age Fischer and Greer for their scenes opposite their now-grownup sons, which makes it seem as if they had them when they were 12; the near-omission of Sadler’s parents from the narrative, which inadvertently turns a co-equal lead character into The Black Friend; and the way Eastwood keeps the terrorist literally faceless during his first few flashback appearances, by focusing on his hands, his feet, his knapsack and wheeled suitcase, and the back of his neck.

I’ve read that Eastwood asked the French government if he could get Khazzani to play himself, too, but was refused. Is this why he portrayed him as a non-person—just another Bad Thing happening to Good People? I wanted to know how Khazzani ended up on that train as well—not because he deserves any sympathy (he doesn’t) but because his is also a tale of social conditioning and sheer willpower, and might have reflected off the main trio’s story in illuminating ways. For an example of how to do this in a thoughtful, responsible manner, see Anurag Kashyap’s 2007 film “Black Friday,” which retold the same bombing from the point-of-view of the terrorists and the police, in two different halves. Eastwood did something similar with “Flags of Our Fathers” and “Letters from Iwo Jima.” But for the most part, he has become increasingly uninterested in that kind of complexity, despite having devoted the first 20-plus years of his directing career to letting us see the evil in good people, and the good in the evil.

While there’s something innately inspiring about Eastwood continuing to crank out films 48 years into his directing career, there’s a downside: his batting average has never been terrific, and his game has slipped a lot since the Iwo Jima films. There are intriguing aspects to nearly all of his films, but he’s only made maybe six or seven that are excellent from start to finish—even the mostly good ones have bad scenes and sections—and in the last 20 years, even his good work has included a lot of ill-considered, amateurish, or flat-out baffling elements, like the screechingly caricatured parents in “Million Dollar Baby,” and Chris Kyle doting on an obviously fake infant in “American Sniper.” Eastwood is famous for working fast and bringing his movies in on time and under budget, and “The 15:17 to Paris” is another example of that legendary efficiency: supposedly he decided to tell the trio’s story after giving them a Spike TV Guys’ Choice Award just 19 months ago. But breeziness is not, in itself, an unassailable virtue. There hasn’t been a single Eastwood film since “Unforgiven” that couldn’t have benefited from script rewrites, plus a few trusted advisors with the nerve to tell him that a particular choice was ill-advised. (I know, I know—who wants to tell Clint Eastwood he’s wrong? Nobody who’s seen him use a hickory stick in “Pale Rider,” for starters.)

The movie’s greatest virtue, which might be enough to make it a critic-proof hit no matter what, is its poker faced sincerity. This extends to faithfully reproducing a Red State worldview that was also showcased in “American Sniper” and “Sully.” A lot of U.S. moviegoers are going to feel seen by this film, and that’s a net gain for American cinema, which is supposed to be a populist art form representing the body politic as it is, not merely as the industry wishes it could be. If only someone could’ve heroically intervened to save this movie.