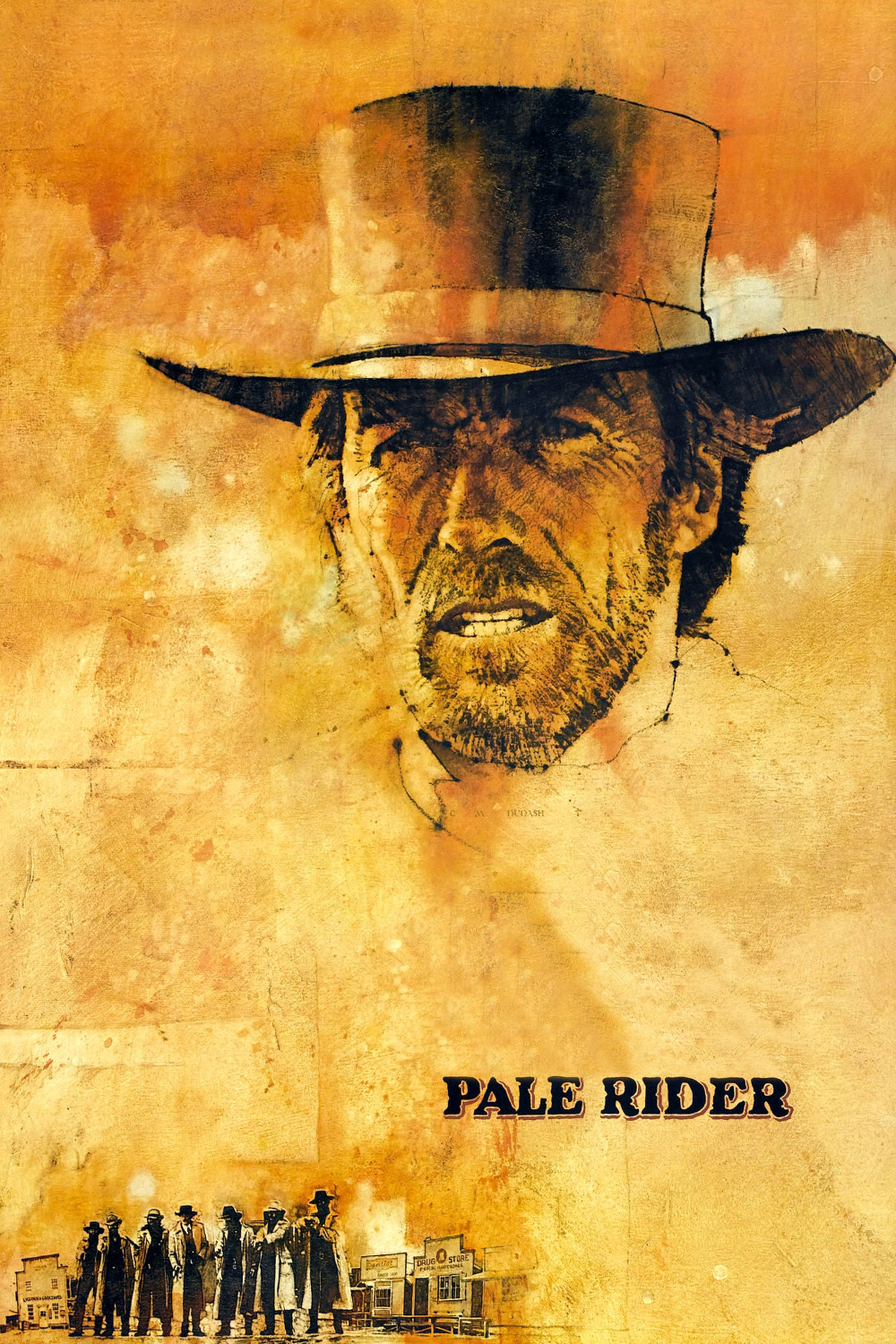

Clint Eastwood has by now become an actor whose moods and silences are so well known that the slightest suggestion will do to convey an emotion. No actor is more aware of his own instruments, and Eastwood demonstrates that in “Pale Rider,” a film he dominates so completely that only later do we realize how little we really saw of him.

Instead of filling each scene with his own image and dialogue, Eastwood uses sleight of hand: We are shown his eyes, or a corner of his mouth, or his face in shadow, or his figure with strong light behind it. He has few words. The other characters in the movie project their emotions upon him. He may indeed be the pale rider suggested in the title, whose name was death, but he may also be an avenging spirit, come back from the grave to confront the man who murdered him. One of the subtlest things in the movie is the way it plays with the possibility that Eastwood’s character may be a ghost, or at least something other than an ordinary mortal.

Other things in the movie are not so subtle. In its broad outlines, “Pale Rider” is a traditional Western, with a story that has been told, in one form or another, a thousand times before. In a small California mining town, some independent miners have staked a claim to a promising lode. The town is ruled by a cabal of evil men, revolving around the local banker and the marshal, who is his hired gun. The banker would like to buy out the little miners, but, lacking that, he will use force to drive them off their land and claim it for his company.

Into this hotbed rides the lone figure of Eastwood, wearing a clerical collar and preferring to be called “Preacher.” There are people here he seems to know from before. The marshal, for example, seems to be trying to remember where he has previously encountered this man. Eastwood moves in with the small miners, and becomes close with one group; a miner (Michael Moriarty) who lives with a woman (Carrie Snodgress) and her daughter (Sydney Penny). He urges the miners to take a stand and defend their land, and agrees to help them. That sets the stage for a series of violent confrontation.

As the film’s director, Eastwood has done some interesting things with his vision of the West. Instead of making the miners’ shacks into early American antique exhibits, he shows them as small and sparse. The sources of light are almost all from the outside. Interiors are dark and gloomy, and the sun is blinding in its intensity. The Eastwood character himself is almost always backlit, so we have to strain to see him and this strategy makes him more mysterious and fascinating than any dialogue could have.

There are some moments when the movie’s mythmaking becomes self-conscious. In one scene, for example, the marshal’s gunmen enter a restaurant and empty their guns into the chair where Eastwood had been sitting moments before. He is no longer there; can’t they see that? In the final shootout, the Preacher has a magical ability to dematerialize, confounding the bad guys, and one shot (of a hand with a gun emerging from a water trough) should have been eliminated–it spoils the logic of the scene.

But “Pale Rider” is, over all, a considerble achievement, a classic Western of style and excitement. Many of the greatest Westerns grew out of a director’s profound understanding of the screen presence of his actors; consider, for example, John Ford’s films with John Wayne and Henry Fonda. In “Pale Rider,” Clint Eastwood is the director, and having directed himself in nine previous films, he understands so well how he works on the screen that the movie has a resonance that probably was not even there in the screenplay.