Directed by Clint Eastwood in what some may take as alarmingly short order following “Jersey Boys” (which was released only six months ago, for heaven’s sake), “American Sniper” proves the dictum “never count an auteur out” by proving itself as Eastwood’s strongest directorial effort since 2009’s underrated “Invictus” pretty much right out of the starting gate. Opening with a brutally suspenseful moment of decision for its titular character, Chris Kyle, the movie establishes all of the things it’s going to be about—and the things it’s not going to be about—with plain but almost breathtaking assurance.

“Sniper” is based on a true story that got more complicated after Kyle himself told it in the book that gives the film its title. Adapted from that book by actor-turned-screenwriter Jason Dean Hall, the story begins, after its Iraq-set prologue, showing Kyle as first a boy and then a young man. A schoolyard bullying incident compels Kyle’s father (Ben Reed) to give a scary dinner-table fire-and-brimstone speech to Chris and younger brother Jeff about showing would-be tough guys who’s boss (“we protect our own”); the weight of expectation seems to jam the two boys down, and in a flash-forward to the boys as young men, they’re leading the aimless lives of wannabe rodeo stars. That all changes when Chris decides to apply to join the Special Forces (the film depicts him doing so after seeing TV coverage of the 1998 attacks on U.S. embassies in Tanzania and Kenya). As he’s developing a new sense of purpose while training, he also meets future wife Taya (Sienna Miller). Post 9/11, the war in Iraq puts Kyle to work as a sharpshooter, and the film depicts his skills in this area as almost eerie.

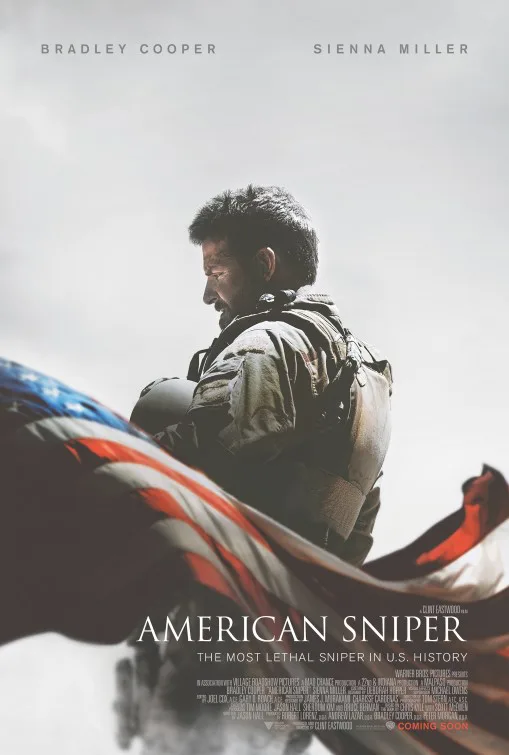

They were so in real life, too, as it happens; Kyle racked up 160 confirmed kills, making him the deadliest such operative in U.S. Navy history. Eastwood’s handling of various battle scenarios, including those in which Kyle is compelled to take down women and children, is typically anti-elaborate for the director. Grim, purposeful, compelling. Violence and its relation to both American history and the American character is one of Eastwood’s great themes as both a filmmaker and a film actor. But he is not a director of an overly analytical or intellectualizing bent, and this turns out to be one of this movie’s great strengths. It has nothing to say about whether the war in Iraq was a good or bad idea. It simply IS, and Kyle is an actor in it, and he’s also a devoted husband and father. But Kyle is more than just an actor in the war: he’s a true believer in what he’s doing, and his intensity in this respect bleeds into his relationships back at home in ways that can’t help but be unsettling. When a fellow soldier is killed in a raid, Kyle returns to the U.S. to attend the funeral.

At the graveside, a relative of the soldier’s reads one of his last letters, expressing doubt and disappointment about the war. On the drive home Chris avers to Taya that what killed his friend was “that letter.” Taya doesn’t know how to respond; the viewer likely doesn’t, either, or at least shouldn’t. The role of Taya (well-played by Sienna Miller; this and her turn in “Foxcatcher” represent a release from Movie Jail for the actress) could have been another stock Complaining Military Wife in other hands. In this film, she’s more complex; she clearly knows that the qualities she admires/loves in Kyle—his rigid loyalty and sharp focus, his determination to see his commitments through—are inextricable from his identity as a military operative. But even a warrior as devoted as Kyle can’t escape being messed with by his mission. As the film continues, and the sniper’s rep grows more fearsome, the nature of his accomplishments gets messier and messier, and by the time the sniper has completed his tour, the viewer has good reason to be a little, or more than a little, frightened by the guy. But Taya is not. This puts the whole story on an oddly suspended note that, as it happens, is resolved by a real-life ending that’s not very Hollywood.

Star Bradley Cooper does some of his best acting ever here. Bulked up to make himself resemble, with respect to body shape, a large-scale nine-volt battery, Cooper suppresses the actorly knowingness he’s brought to most of his prior screen roles and gives his character here a simultaneous credulousness and edge. He feels like a dangerous guy—but not a malicious one. His lack of self-doubt never comes off as alienating in its steadfastness, even at moments when it seems like it’s misplaced, as when Kyle finds out for the last time that he can’t really be his brother’s keeper. Moments such as that one, and they are strewn throughout the movie, are what make “American Sniper” one of the more tough-minded and effective war pictures of post-American-Century American cinema.