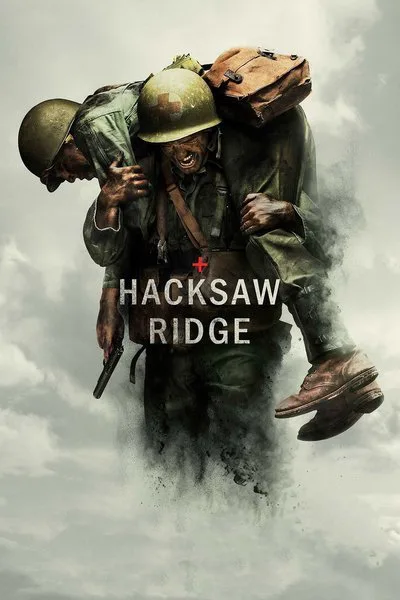

“Hacksaw Ridge,” about a pacifist who won the Medal of Honor without firing a shot, is a mess. It makes hash of its plainly stated moral code by reveling in the same blood-lust it condemns. But it’s also one of the few original action movies released in the last decade, and one of the only studio releases this year that could sincerely be described as a religious picture. Of course, it’s directed by Mel Gibson, who rose to international stardom in R-rated action flicks and went on to become the true heir to Sam Peckinpah, directing a series of astoundingly violent films with cores of spirituality: “Braveheart,” “The Passion of the Christ” and “Apocalypto.” True to form, “Hacksaw Ridge” draws equally on Gibson’s bottomless thirst for mayhem and his sincerely held religious beliefs—or some of them, anyway. It’s a movie at war with itself.

The first half lays out the childhood and adolescence of its hero, Desmond T. Doss (Andrew Garfield), a Seventh-day Adventist turned U.S. Army corporal. Set in Virginia hill country in the ’20s and ’30s, it’s shot in the creamy hues of a Norman Rockwell painting, and filled with earnest, Old Hollywood-styled exchanges about violence and pacifism. The second half is set during the Battle of Okinawa, where Doss, who described himself as a “conscientious collaborator” rather than objector, rescued 75 fellow infantrymen injured by the Japanese; it feels like an attempt to one-up the D-Day sequence in “Saving Private Ryan,” and if sheer bloody explosive nastiness were the only measure, you’d have to declare “Hacksaw Ridge” the winner. The combat pays nearly as much attention to the rending, burning and perforating of flesh as it does to the hero’s anguish and ingenuity. Gibson shows soldiers using mortar shells as homemade grenades (as in the climax of “Saving Private Ryan”), shifts into glorious slow-motion to showcase a soldier kicking an enemy’s lobbed grenade away, and treats us to the surreal and inappropriately comic sight of Doss towing a paraplegic infantryman on a homemade sled while the man cuts down bushels of Japanese soldiers with a sub-machine gun.

This stuff feels like a violation of the spirit of Doss’ moral code, if not its letter. But the first half, which channels the majestic squareness of a John Ford family drama, is weird, too. It’s myth-making with a dash of self-help and Scripture, but Gibson keeps trying to jazz things up with violence or the threat of violence, even when the scenes don’t seem to call for it. Familiar movie situations, such as Doss taking his future wife Dorothy Schutte (Teresa Palmer) out on a date or getting to know his bunk-mates, are interrupted by horror movie-style jump scares or fused to bits of black comic suspense (we know somebody’s going to get maimed by the knife that a soldier is brandishing when Doss enters the barracks; the only questions are which one and when). This is the directorial equivalent of Gibson the actor working Three Stooges shtick into otherwise straightforward dialogue scenes—either a nervous tic or a compulsion. The wide shots of corpses piled up, the shots of Doss posed like Christ or lit by heavenly sunlight streaming through windows, and the moments when Doss treats enemy soldiers with compassion, are a lot more on-message.

All that said, “Hacksaw Ridge” seems aware of its inability to present the horrors of war in a consistently non-thrilling, non-cool way. There are even moments where the film seems ashamed that it can’t live up to Doss’ example—particularly when other characters question Doss’ belief that violence is never justified and that there is no real distinction between killing and murder. What you see on other characters’ faces in these scenes is not contempt but incredulity, followed by petulance and finally denial. They can feel the truth of what Doss is saying. But they can’t imagine the world being anything other than what it is, a place ruled by brute force and cruelty. The rifles that Doss refuses to pick up are described as girls, women, mates, “perhaps the only thing in life you’ll truly love.” The other soldiers’ crude sexual talk and casual sadism are contrasted with Doss’ sweetness, piety and chastity. Doss’ drill sergeant (Vince Vaughn, effectively typecast as a charismatic bully) and other commanding officers keep pressuring Doss to pick up a rifle. When he refuses, they humiliate him and sign off on his hazing; his own platoon-mates call him “coward” and “pussy.” They don’t want to break or kill Doss, just drive him from their sight, perhaps so they won’t have to second-guess themselves each time they lay eyes on him.

It’s worth pointing out here that Doss is the child of an alcoholic World War I veteran, Tom (Hugo Weaving). The film’s own contradictions are embodied in Doss’ dad. He preaches the virtues of nonviolence, rails against the romanticizing of war, visits the graves of childhood friends killed at the Battle of Belleau Wood, and doesn’t want Doss or his older brother Hal (Nathaniel Buzolic) to enlist after Pearl Harbor. But he’s also self-pitying, quick to anger, and beats his wife Bertha (Rachel Griffiths) and their sons. He wants to change and knows why he should. But he can’t.

Tom Doss’ drinking problem feels like more than just a biographical detail. The script, credited to Andrew Knight and playwright Robert Schenkkan (“All the Way“), keeps returning to Tom. The hero’s pacifism seems as much a rejection of his dad’s angry brokenness and inability to control his temper as a reaction to almost killing his brother in a childhood scuffle. Also of interest: like Sam Peckinpah, Gibson has struggled with alcoholism, he has bipolar disorder and rage issues as well, and as an artist he is addicted to violence. In its more thoughtful moments, the film treats intoxication with violence, both real and fictional, as a species-wide addiction—one that can’t easily be broken. I’d be shocked if a director as attuned to mythic signifiers as Gibson weren’t trying, in his own fumbling way, to explore this idea.

Too bad action-film awesomeness is the intoxicant that “Hacksaw Ridge” can’t quit. You feel the movie fighting to suppress its urge to glorify violence and treat the Japanese as sinister hordes. Even in non-war scenes, it can’t stop reaching for the bottle, and there’s a wave of shame when it falls off the wagon. A lingering close-up of guts and goop is followed by a shot of the hero looking appalled or terrified, as if to rebuke the director’s gifts.

“Hacksaw Ridge” seems to know that its hero is better than anyone around him, perhaps better than the movie that tells his story. This comes through strongly in the relationship between Doss and fellow infantryman Smitty (Luke Bracey), a far more convincing love story than the one between Doss and his gal. Of course Smitty loathes and torments Doss, then comes to respect and even revere him. The way Smitty looks at Doss during the battle of Okinawa recalls the way the disciples gazed upon Jesus in Gibson’s “The Passion of the Christ”—as a promise and a mystery; a person so strikingly different from other people, so fully formed, so serenely and undeniably good, that he seems more angel than man. Garfield’s performance humanizes him. For a long time you think Doss is an idealized figure, free of neuroses and complications. But after a while you see the darkness in him, and you believe it exists because of the thoughtful way Garfield has prepared you.

This film is inept and beautiful, stupid and amazing. It doesn’t have the words or images to express how deep it is. That’s why it’s more interesting to talk about than it is to watch. I wonder what the real Doss, who died in 2006, would have thought of it.