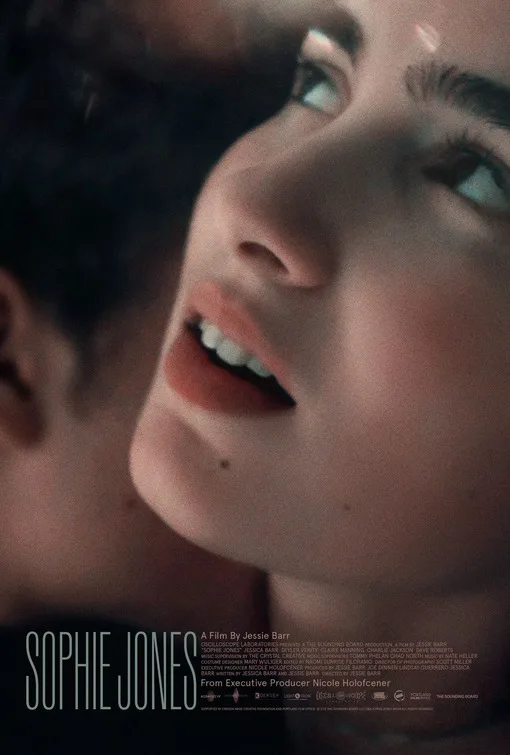

Is there ever a point at which grief gets easier? 16-year-old Sophie Jones (Jessica Barr) is going through it. Her mother has recently died. She feels tangible distance from her younger sister Lucy (Charlie Jackson) and their father Aaron (Dave Roberts). Every day feels like a struggle that just bleeds into another, and another, and another. Nothing feels right—and that unease, when coupled with Sophie’s adolescent sexual awakening, makes for a complicated mix that “Sophie Jones” tracks with rawness, poignancy, and slightly too much vaguery.

The film is a family affair, directed by Jessie Barr and written by Jessie and her cousin Jessica, who also stars in “Sophie Jones” as its titular teenager. The Barrs drew from their own personal experiences as adolescents who each lost a parent to cancer, and the result is that “Sophie Jones” feels deeply authentic in its understanding of grief. There are no grand blowouts here, no massively emoting moments. Instead, “Sophie Jones” rejects linear storytelling to operate more as a series of vignettes, spread out over two or so years, which follow Sophie as she struggles to mourn her mother, develop her own personality, and explore her sexual identity. We jump forward sometimes days, sometimes weeks, sometimes months, but the focus is always two-pronged: the inner sadness Sophie carries that she rarely shares with anyone else, and the outer sexual confidence—tiptoeing into aggression—that she displays as she jumps from guy to guy.

On the one hand, this centers Jessica Barr’s organic, naturalistic performance, allowing the actress space to work out the myriad oppositional complexities related to mourning and desire. When we meet Sophie, she’s opening the bag of her mother’s ashes, sifting through them with her fingers, and putting some in her mouth (a tic she’ll use as a defensive mechanism throughout the film, also with blood). Is it macabre that in the next scene, she’s swiping on some lipgloss and sucking on a lollipop while proposing a hookup arrangement with classmate Kevin (Skyler Verity)? Maybe! But this sort of vacillation is Sophie’s new normal. She hasn’t been doing drugs, drinking, or engaging in self-harm, she tells a therapist—but what she doesn’t share is that her sexual experimentation is gaining her a certain reputation.

No interaction is exactly the same. There’s Kevin, who clearly has feelings for Sophie that go further than just their hookups; she shuts him down. There’s a senior who tells a friend of a friend that he thinks Sophie is cute; suddenly she’s planning to lose her virginity to him. There’s Sophie’s closest guy friend, who has been by her side for years and who has never made a move—but whom Sophie tries to forcibly kiss in her car. Sophie’s grief and her sexual choices are probably interlinked, as Sophie’s worried best friend Claire (Claire Manning) suggests, but Sophie doesn’t care about being looked down upon by her classmates. So what if other girls laugh at her? So what if a random acquaintance pulls her aside to tell her she’s embarrassing herself? Could any of that really be worse than losing her mother? “Sophie Jones” doesn’t shy away from the reactions Sophie receives, but it refuses to judge her, either.

That’s an admirable, arguably essential, quality for coming-of-age stories; think of how other recent films in this subgenre, like “Lady Bird,” “Skate Kitchen,” and “Hala,” also treat their female characters with the respect that previous generations of films about young women often lacked. “Sophie Jones” equates being inside its character’s headspace with being close to her physically: tight shots of her profile as she drives around, a floating camera in her bedroom as she somberly thinks about her mother, and well-edited hookup scenes that capture her gleeful abandon or painful regret. But on the other hand, “Sophie Jones” sometimes stumbles in this narrowness. The film’s alignment with Sophie is so thorough that there are no scenes without her, which makes some of these time jumps disorienting. If we’ve been with Sophie this whole time, how did weeks just pass? When did the relationship she suddenly has with one of these guys occur? What happened in the time between, say, New Year’s, and when Sophie is suddenly getting ready to leave for college? The narrative connections are sometimes so hazy that Sophie’s behaviors read more as erratic than as spontaneous, and additional plot details in the Barrs’ script might have better contextualized some of her personality shifts.

Nevertheless, this approach favors Jessica Barr’s inhabiting of the character she helped write, and that is undoubtedly the greatest strength of “Sophie Jones.” Watching it, I was reminded of Margaret Atwood’s quote from the novel Alias Grace: “When you are in the middle of a story it isn’t a story at all, but only a confusion.” Nearly every scene in “Sophie Jones” is either meditative or combative in some way, and Barr nails the flickering, shifting, visceral emotions of adolescence. The deadpan way she says of oral sex, “I could just bite his dick off if I wanted to,” and then her little laugh afterward; her utterly unimpressed delivery of, “This is sex? This is it?”; the way her face shifts from tense rapture to barely veiled perturbation when a guy asks her, “You’re on birth control, right?”; how she lets her sentences trail off when she’s tired of a conversation. Even when the script relies too much on her affect, the actress remains impressively self-possessed, and the film’s framing of her is evocative. “Sophie Jones” is a promising effort from both Barr women.

Available on VOD today.