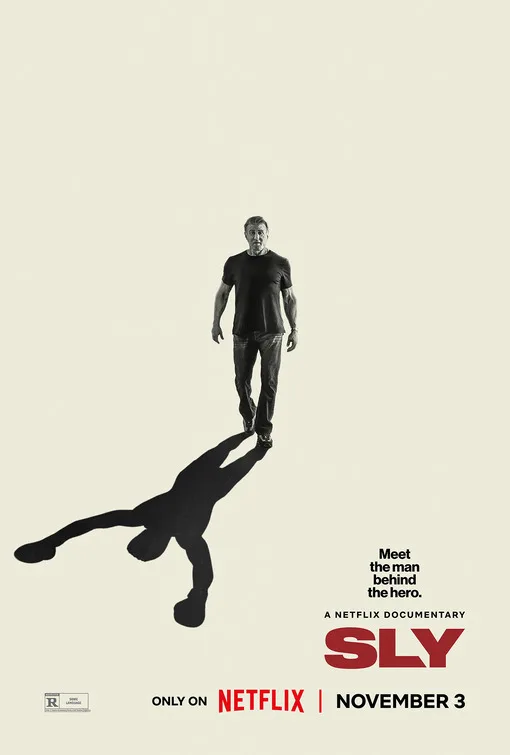

Sylvester Stallone has always been known for his physicality, but Thom Zimny’s documentary “Sly” confirms that it was his voice that made him a star.

Actually, as the movie makes clear, there are two voices, intertwined. One is the New York-accented baritone croak that Stallone speaks with, slurred by an accident during delivery that paralyzed parts of his face. The other voice is the one that comes off the pages of the scripts that Stallone writes (and, in many cases, rewrites—sometimes on the spot). Stallone has only been nominated for one major writing award, Best Original Screenplay for the first “Rocky,” which seems as much of a reward for creating his own Cinderella story in Hollywood as for the work itself. But as “Sly” demonstrates, every project Stallone touches becomes a Stallone film, even if it wasn’t intended as such. The words and stories and themes come from a personal place, whether he’s inhabiting human-scaled characters like the boxer Rocky Balboa and the meek sheriff Freddy Heflin in “Copland,” or playing jacked-up killers like super-soldier John Rambo, the snarling heroes of “Cobra” and “Demolition Man” and “Judge Dredd,” and mercenary Barney Ross in the “Expendables” series.

Everything he works on ends up sounding like him, because Stallone made it sound like him or because younger writers who grew up watching his movies knew how to write for him. For better or worse, there was never any mistaking his work for anybody else’s. And after an astounding fourteen-year stretch that contained the first five “Rocky” movies and three “Rambo films,” he kept reinventing himself, alternating red meat action flicks with attempts at farce (“Oscar,” “Stop! Or My Mom Will Shoot“) and romance (“Rhinestone“). Even Arnold Schwarzenegger—his only plausible rival for the 1980s and ’90s he-man cinema crown—tells “Sly” that he was in awe of Stallone’s ability to stay a half-step ahead of him even at the peak of his ambition and fame, and to have enough focus and drive to simultaneously wear four hats (actor, writer, director, producer) on signature projects.

“Sly” gives Stallone his due as a pop culture force. Director Zimny is best known for his documentary and music video work for Bruce Springsteen. He brings a Springsteen-y working-class-hero framing to Stallone, having him revisit his tough childhood in Hell’s Kitchen, New York City; setting his legend in opposition to the nepotism and trust-fund babies who dominate the entertainment industry; and threading his painful relationship with his father Francesco “Frankie” Stallone, Jr. through much of the story. Stallone’s younger brother, actor/musician Frank Stallone, joins Sly in speaking frankly about their father’s seemingly unrelenting meanness.

Stallone’s father took young Sly to Maryland after splitting from the boys’ mother, wrestling promoter Jackie Stallone, bought some cheap horses, and took up polo. Jackie, meanwhile, brought Sly’s kid brother with her to Philadelphia, the setting for most of the “Rocky” series. The movie is powerful when it focuses on Stallone recounting the countless disappointments of his relationship with his father, usually in wry, understated language that only amplifies how awful it must have been. When the brothers became adults, their father shifted from verbal and physical abuse to jealousy, pettiness, and public displays of knife-twisting cruelty; it all seemed driven by the pain of watching his children exceed him, a sight that would fulfill a dream for most parents. Stallone never stopped trying to win his father’s love, often by purchasing it with extravagant gifts.

Elsewhere, “Sly” is a frustratingly unrealized work, hovering on the edge of insight. It was smart of Zimny to put Stallone front and center and let him guide the audience through his life with the same affable, eloquent, man-of-the-people energy that he brought to so many talk show appearances over the years. But the downside of that access, perhaps, is a film that sands the roughest edges off Stallone and his work.

Stallone was an uncouth palooka punchline for legacy Hollywood and the snarks of journalism. “Sly” barely touches on that, except to let Stallone and other interviewees call him an outsider or underdog without delving into what the words meant in context of an Italian-American New Yorker with a speech impediment suddenly becoming rich and famous without learning to be smooth and classy first. Nor is there much about Stallone’s marriages, save his third, which is treated glancingly, or his children (except for Sage Stallone, who died unexpectedly at 36). When Stallone says he regrets having put his work ahead of his parenting, the moment is so affecting that one wishes the film had probed it more.

You can’t quite call “Sly” a deep dive into the work, either. It spends much of its first half getting to the original “Rocky” and sprints through most of the rest, with pauses for highlights like the “Rambo” films and “Copland.” And it elides some aspects of what Stallone’s career, in a larger sense, meant to 20th-century America. He was a poster boy for certain mindsets. It seems hard to imagine today, with Rocky defined for younger generations as “Unc,” the crusty old mentor of Donnie Creed in the “Creed” series, and jocular action figure Barney Ross in the “Expendables” franchise, but the “Rocky” movies in the ’70s and ’80s were “issues” as well as films, as discussed for their exploitative racial politics as their entertaining qualities. The character of Apollo Creed in the first film was Muhammad Ali the way a white ethnic Nixon-era “hardhat” would have viewed him—as a rich and arrogant braggart; when Apollo was humbled and softened in the third film, it was to position him as a preferable alternative to Clubber Lang, a snarling ghetto gargoyle.

The “Rambo” series, meanwhile, started out as a wilderness survival tale with a traumatized Vietnam vet as its hero and hippie-hating backwoods cops and National Guardsmen as its antagonists, then took a right-wing turn in 1985 with the second entry in the series, a P.O.W. rescue fantasy wherein Rambo killed bushels of Vietnamese and dozens of Russians. The “Rocky” series joined Rambo in Reagan-land that year with “Rocky IV,” which pitted Rocky against a gigantic, scowling, platinum blonde Soviet who seemed to have stepped out of a James Bond flick.

Throughout most of the next 15 years, Stallone became the anti-Springsteen, incarnating white ethnic grievance and reactionary fervor and joining Schwarzenegger, Clint Eastwood, and Bruce Willis in stumping for right-wing politicians. A 1985 Newsweek cover story headlined “Showing the Flag: Rocky, Rambo, and the Return of the American Hero” anointed him as the successor to John Wayne. It would have been fascinating to hear Stallone talk about all this with his customary humor and self-deprecating insight, but “Sly” doesn’t so much downplay politics as duck them, like Rocky avoiding a haymaker. (I’d bet good money that two of Zimny’s key interviewees, New York Times culture writer Wesley Morris and writer/director Quentin Tarantino, had plenty to say on all of these topics, whether or not Zimny asked for their opinions.)

There might be a more challenging movie in the deleted footage. Stallone gives great quote and is willing to go into controversial areas when interviewers encourage him. He was in his mid-seventies when “Sly” was shot and had recently done a feature-length documentary about his artistic process, “The Making of Rocky vs. Drago,” focusing on his belated re-cut of “Rocky IV,” which restored a lot of the character development he’d junked to shorten the film’s running time in 1985. That film will likely be more satisfying for devotees of Stallone the filmmaker and icon, as it goes into the nuts-and-bolts of filmmaking, image-shaping, and psychology, and provides just as much personal insight. And oddly, although it’s very much Stallone’s movie, it feels less guarded, and less like an ad for a self-created brand.

On Netflix now.