Alfonso Cuaron’s “Roma” opens with a close-up shot of a stone-paved driveway. We see soapy water cascade over the rock, as someone off-camera is cleaning it. In the reflection of the water, we can see the sky, although even that reflection undulates and changes as the water moves. A plane then moves across the field of view within the reflection. It sounds so simple but there is so much in this sequence of images that is reflected in the film to follow: a natural flow of life—water, stone, air—while also presenting us with the concept of the micro within the macro, like a plane against the sky. So much of “Roma” repeats that concept of the personal story against a backdrop of a larger one—the face in the crowd, the human story in the context of a societal one. Cuaron has made his most personal film to date, and the blend of the humane and the artistic within nearly every scene is breathtaking. It’s a masterful achievement in filmmaking as an empathy machine, a way for us to spend time in a place, in an era, and with characters we never would otherwise.

The woman cleaning that driveway is Cleo (Yalitza Aparicio), a servant for a wealthy family in Mexico City in the ‘70s. Cleo is no mere maid, often feeling like she is a part of the family she serves more than an employee—although she is often reminded of the latter fact as well. She may go on trips with them and truly love the children, but she also gets admonished for leaving her light on too late at night as it wastes electricity. Cleo is a quiet young woman, eager to do a good job, and able to stay out of the way when controversy arrives within the family, especially with the distant, often-absent patriarch.

Everything changes for Cleo after an affair with a cousin of her friend’s boyfriend results in a pregnancy. Cleo’s employers offer to help their favorite servant with the pregnancy, taking her to the doctor and supporting her with whatever she needs, but the child’s father disappears, and Cleo looks worried about what her future holds. “Roma” spends roughly a year in the life of Cleo as she plans for motherhood, tries to support a family that is coming apart, and simply moves through a loud, changing world.

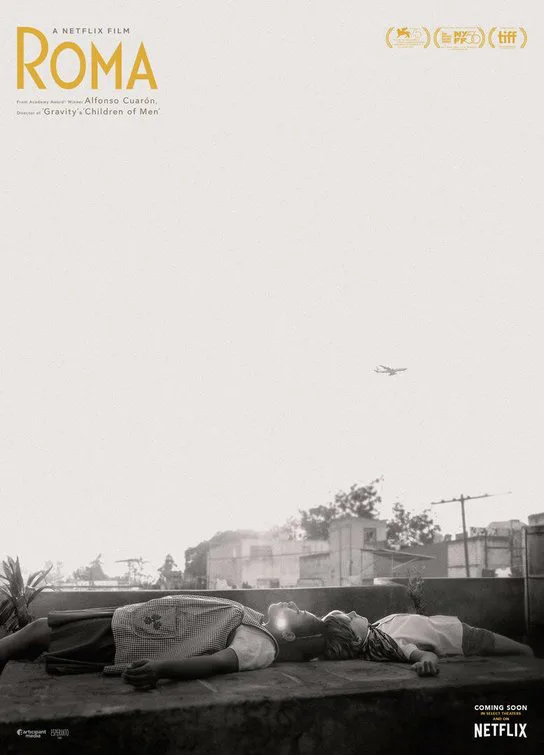

Cuaron, who shot the film in gorgeous black-and-white himself (and clearly learned a thing or two from regular collaborator Emmanuel Lubezki), adopts a fascinating visual style for “Roma” in that he rarely uses close-ups, keeping us at a distance from Cleo and his other characters, and allowing the details of the world around them to come to life. Without over-using the trick, which would have resulted in a cluttered film, Cuaron often places Cleo in a tableau that could be called chaotic, whether it’s a market teeming with people behind her or even just the home in which she spends so much of her time, full of noisy children, relatives, and servants. Cleo’s existence is a crowded one, and it almost feels like it gets more so as the film goes along, mirroring her increasing concern at the impending birth of her child. With some of the most striking imagery of the year, “Roma” often blends the surreal and the relatable into one memorable image.

Throughout “Roma,” Cuaron uses his mastery of visual language to convey mood and character in ways his mostly-silent protagonist cannot. There is no score, and yet “Roma” feels aurally alive, largely because of the veracity of Cuaron’s attention to detail. There’s a tendency for filmmakers who attempt to make something that could be called “poetic” to get loose with detail. The idea is that poetic cinema can’t be realistic cinema. What’s so stunning about “Roma” is how much Cuaron finds the poetry in the detail (this is also true of Barry Jenkins’ “If Beale Street Could Talk,” one of the other great movies of 2018). The film is remarkably episodic—so much so that its lack of driving narrative may disappoint people when they watch it on Netflix—but it’s designed to immerse you, to transport you, and those who go with it will find themselves rewarded. Cuaron’s film climaxes in a couple of emotional scenes that will shake to the core those who care about these characters.

Cuaron has said that this film is a tribute to the women in his life and “the elements that forged me.” With that obviously personal angle driving the production, “Roma” often plays out like a memory, but not in a gauzy, dreamlike way we so often see from bad filmmaking. Every choice has been carefully considered—that wide-angle approach allows for so much background detail—and yet “Roma” is never sterile or overly precious with its choices. It’s that balance of truth and art that is so breathtaking, making Cuaron’s personal story a piece of work that ultimately registers as personal to us, too. And you walk out transformed, feeling like you just experienced something more than merely watching a film. That kind of movie is incredibly rare—we’re lucky if get one a year. “Roma” is that special.

I don’t often get as personal as some critics do in reviews, but how strongly I feel about this film seems to warrant one more closing thought. By virtue of being blessed to work here, I’m often asked what I think Roger Ebert would have thought about some of the films that have been released since he passed. It’s emotionally overwhelming to consider what he might have written about “Moonlight” or “Selma” and so I try not to go down that mental rabbit hole, but I felt that absence perhaps most greatly while watching “Roma.” When it ended, I thought more than ever about how he would have written about it. I think that’s because it so completely embodies what he considered the role of great cinema as an empathy machine. We should be thankful there are films like “Roma” keeping that machine humming.

This review was originally filed from the Toronto International Film Festival on September 11th.