Florida is the ideal state for film noir. Not the Florida of retirement villas and golf condos, but the Florida of the movies, filled with Spanish moss and decaying mansions, sweaty trophy wives and dog-race gamblers, chain-smoking assistant DAs and alcoholic newspaper reporters. John D. Macdonald is its Raymond Chandler and Carl Hiaasen would be its Elmore Leonard, if Leonard hadn’t gotten there first.

Noir is founded on atmosphere, and Florida has it: tacky theme bars on the beach, humid nights, ceiling fans, losers dazed by greed, the sense of dead bodies rotting out back in the Everglades. (Louisiana has even more atmosphere, but noir needs a society where people are surprised by depravity; Louisiana takes it for granted.) ”Palmetto” is the latest exercise in Florida Noir, joining ”Key Largo,” ”Body Heat,” ”A Flash of Green,” ”Cape Fear,” ”Striptease,” and ”Blood & Wine.” The movie has elements of the genre and lacks only pacing and plausibility. You wait through scenes that unfold with maddening deliberation, hoping for a payoff–and when it comes, you feel cheated. Watching it, I was more than ever convinced that Bob Rafelson’s ”Blood & Wine” was the movie that got away in 1997–a vastly superior Florida Noir (with a Jack Nicholson performance that humbles his work in ”As Good As It Gets”).

Both films depend on our sense of rich, eccentric people living in big houses that draw the attention of poor people. Both involve deception and hidden identities. Both heroes are once-respectable outsiders, driven to amateurish crime by desperation. Both involve older men blinded to danger by younger women with beckoning cleavage. ”Blood & Wine” is the film that works. ”Palmetto” is more like a first draft.

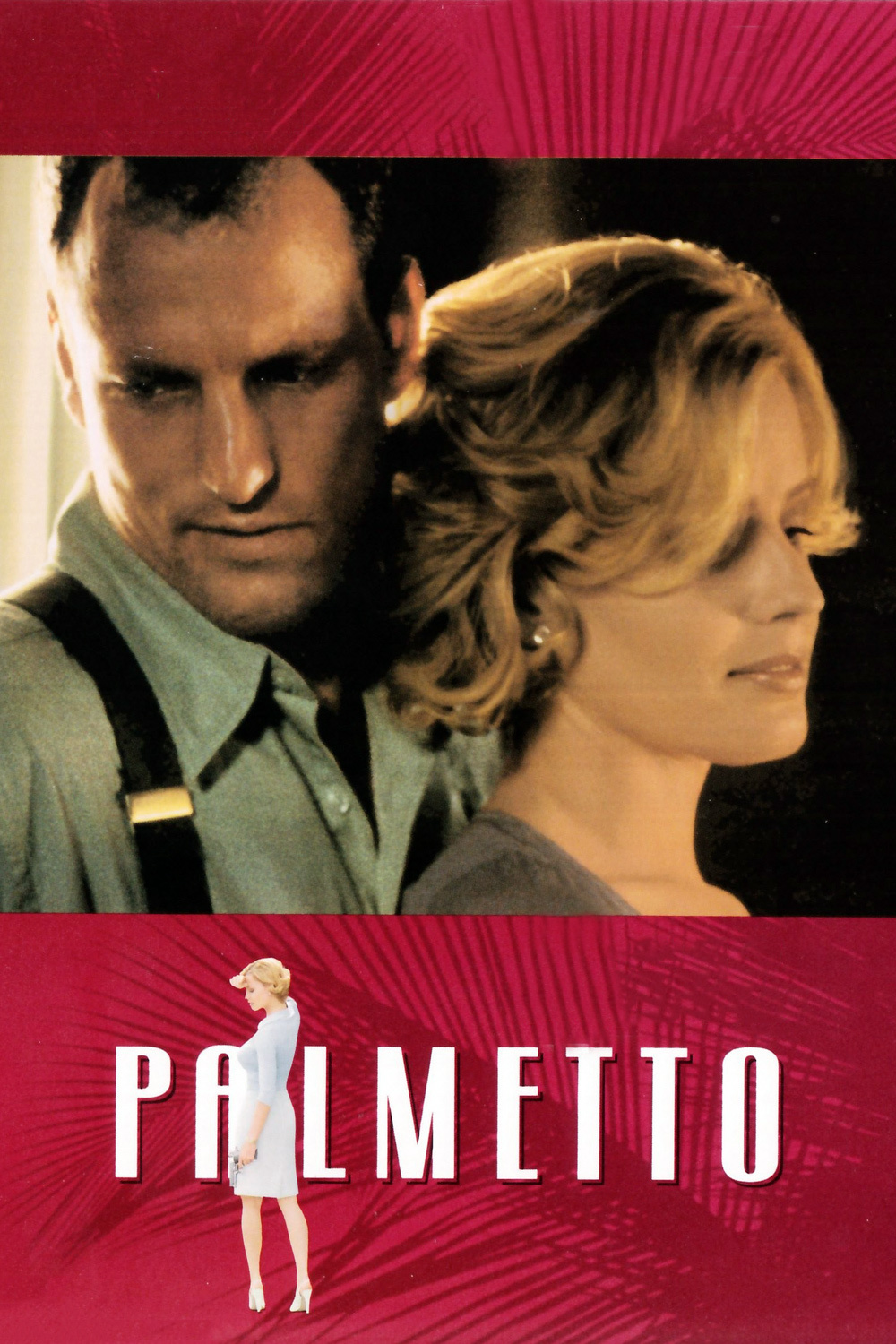

Woody Harrelson stars as Harry Barber, a newspaper reporter who tried to expose corruption in the town of Palmetto and was framed and sent to prison. After two years his conviction is overturned, and he’s released–by a judge who renders the verdict over closed-circuit TV. When Harry starts screaming that he wants his two years back, the judge dismisses him by clicking the channel-changer.

Harry wants to start over, anywhere but in Palmetto. But he’s drawn back by his ex-girlfriend, Nina, an artist played by Gina Gershon. He looks for work, can’t find it and amuses himself by hanging around days in bars, ordering bourbon and not drinking it (this is not recommended for ex-drinkers). One day a blond named Rhea (Elisabeth Shue) undulates into the bar, makes a call and outdulates without her handbag. Harry finds it in the phone booth, she reundulates for it, and they fall into a conversation during which Harry does not drink bourbon and Rhea holds, but does not light, a cigarette (”I don’t smoke”).

The sense that Harry and Rhea are holding their addictions at bay does not extend to sex, which Rhea uses to enlist Harry in a mad scheme. She’s married to a rich old coot named Felix (Rolf Hoppe) who is dying of cancer, but may linger inconveniently; meanwhile, her stepdaughter Odette (Chloe Sevigny, from ”Kids”) is threatening to run away rather than be parked in a Swiss boarding school. Rhea’s proposal: Harry fakes Odette’s kidnapping, Felix pays $500,000 in ransom, Harry keeps 10 percent for his troubles, Odette has her freedom with the rest. Lurking in the background: Michael Rapaport, as Felix’s stern houseboy.

Well, what mother wouldn’t do as much for a child? Harry’s misgivings are silenced by Rhea’s seductive charms, while Nina observes in concern (her role reminded me of Barbara Bel Geddes in ”Vertigo”–the good girl with the paint brush, looking up from her easel each time the bad boy slinks in after indulging his twisted libido).

Harry is, of course, spectacularly bad as a kidnapper (I liked the scene where he types a ransom note on his typewriter and flings it from a bridge, only to see that he has misjudged the water depth and it has landed in plain sight on the mud). While he leaves fingerprints and cigarette butts (”DNA? They can test for that?”) about, there’s a neat twist: The assistant D.A. in charge of the kidnapping case (Tom Wright) hires him as a press liaison. So the kidnapper becomes the official police spokesman.

All of the pieces are here for a twisty film noir, and Harry’s dual role–as criminal and police mouthpiece–is Hitchcockian in the way it hides the perp in plain sight. But it doesn’t crackle.

The director, Volker Schlondorff (”The Tin Drum”) doesn’t dance stylishly through the genre, but plods in almost docudrama style. And screenwriter E. Max Frye, working from James Hadley Chase’s novel Just Another Sucker, hasn’t found the right tone for an ending where victims dangle above acid baths. The ending could be handled in many ways, from the satirical to the gruesome, but the movie adopts a curiously flat tone. Sure, we have questions about the plot twists, but a better movie would sweep them aside with its energy; this one has us squinting at the screen in disbelief and resentment.

The casting is another problem. Gina Gershon and Elisabeth Shue are the wrong way around. Gershon is superb as a lustful, calculating femme fatale (she shimmers with temptation in ”Bound” and ”This World, Then the Fireworks”). Shue is best at heartfelt roles. Imagine Barbara Stanwyck waiting faithfully behind the easel while Doris Day seduces the hero, and you’ll see the problem. Woody Harrelson does his best, but the role serves the plot, so he sometimes does things only because the screenwriter needs for him to. ”Palmetto” knows the words, but not the music.