In recent years, Paul Schrader has been crafting idiosyncratic films about men who keep tabs on themselves — journal writers, all, in the tradition of Robert Bresson’s “Diary of a Country Priest,” one of the touchstone films in Schrader’s philosophy. Bresson’s work is one he wrote about at length in his thesis-turned-book, Transcendental Style in Cinema: Ozu, Bresson, and Dreyer and one that profoundly influenced his own work as both a screenwriter and writer-director. You can find direct quotes from Bresson in his and Martin Scorsese’s “Taxi Driver,” in Schrader’s third solo picture as writer-director “American Gigolo,” and more.

Bresson’s films depict characters striving toward grace; it’s arguable as to whether they find it. (Check out Bresson’s late film “The Devil, Probably” for a particularly troubling treatment of the struggle.) In Schrader’s late work, grace comes in the form of earthly love, the kernel of optimism that caps last year’s “Master Gardener.” Like his two films before “Gardener” (“First Reformed” and “The Card Counter“), that 2023 picture opens with a man sitting at a desk, writing in a journal, a decidedly Bressonian image. “Gardener” completed something Schrader called, perhaps not entirely seriously, his “Man in a Room” trilogy. He explained to journalist and critic Esther Zuckerman, “It’s about the evolution of the soul of these people who are locked off in their rooms and can’t reach out and touch anyone.”

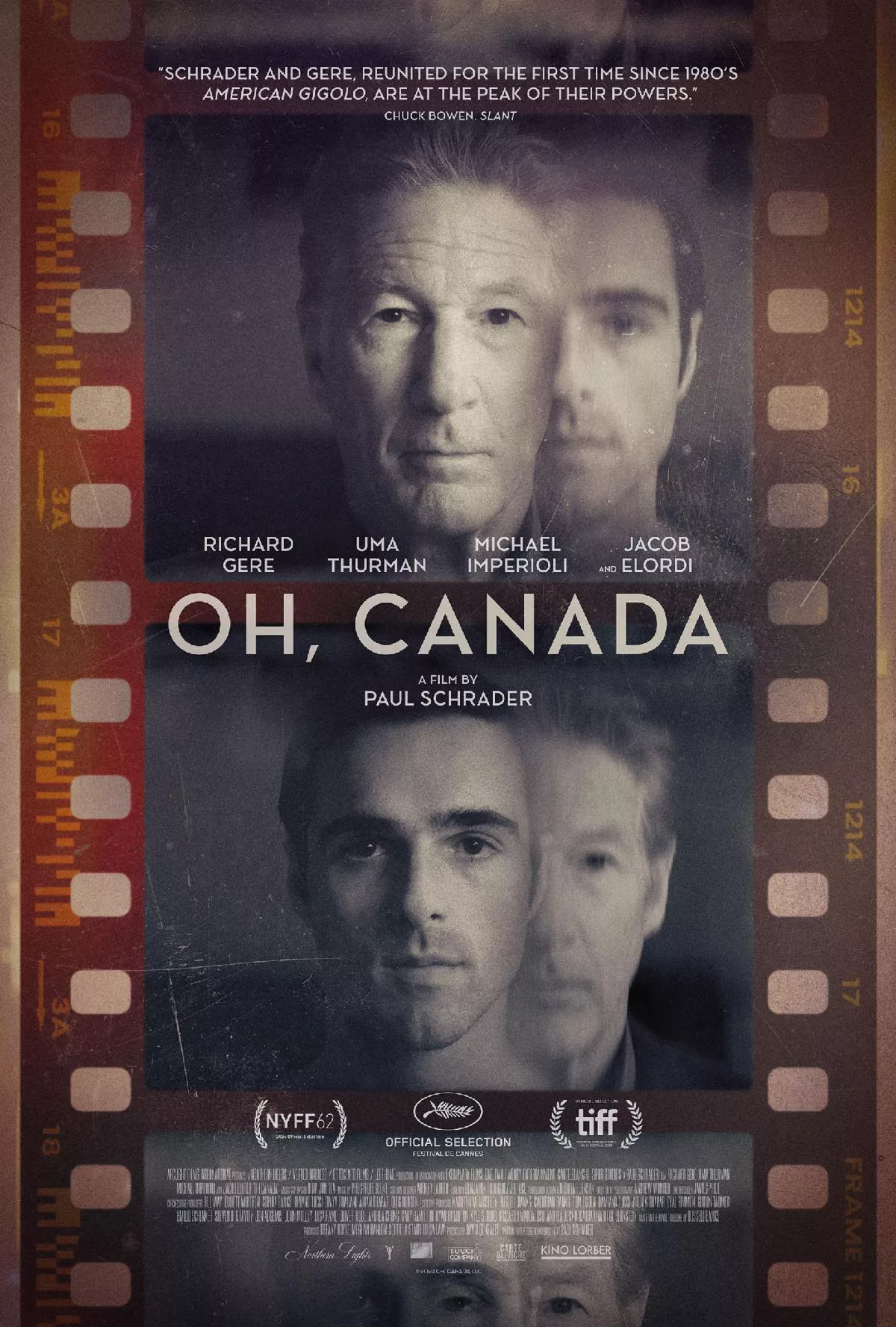

In “Oh, Canada,” adapted by Schrader from the Russell Banks novel Foregone (apparently the title Schrader uses was the one Banks preferred), the man is at a room but not sitting at a desk and writing. Leonard Fife, played with searing conviction by Richard Gere, is lying in a bed, dying of cancer. Fife is a writer and filmmaker whose documentaries, often provocative exposés, insisted on rigorous, sometimes painful honesty. As he faces down death, Fife is attended by a younger documentarian, Malcolm (Michael Imperioli) who in a sense is giving Fife a taste of his own medicine.

Fife’s interrogation of his own past centers on how he became, well, a Canadian filmmaker. The younger Fife, played in flashbacks by Jacob Elordi, is a college-bound U.S. citizen, an idealist who may well be swept up by military conscription—the “draft” that was to be “dodged” by many by a defection to the great white North — but has to reconcile all that he may leave behind, materially, emotionally, and spiritually, before he makes his step across the border.

The astute critic Jonathan Romney noted that the dying Fife’s self-contradictory accounts of his life, set down as cinematic fact in Schrader’s depictions, bring to mind the muddled memories at play in “Providence,” the 1977 collaboration between time-obsessed director Alain Resnais and British dramatist David Mercer. But the Resnais film had a playfulness that resulted in a trenchant tragicomedy (and in fact even included an appearance from a werewolf of sort); while “Oh, Canada” has moments of mordant humor, its ultimate mode is the elegiac.

It is, however, as much a film about filmmaking as it is about death. Schrader is nearly unique among working filmmakers as he comes from a religious upbringing that took the Mosaic commandment against the making of graven images very seriously. Fife’s ultimate reckoning is both with death and with what he thought was the truth. In a playful but pointed exchange, Fife is revealed to have invented a camera modification very much like Errol Morris’ much-vaunted “Interrotron,” which allows an interview subject to look directly into the camera and see the person asking the questions in a monitor attached above the lens. Schrader puts across a skepticism as to whether such a device is better at getting “the truth” than any other method of inquiry. Godard famously called cinema “truth 24 frames-per-second,” as film history proceeds, that idea seems almost quaint. Schrader acknowledges it, plays with it, and subverts it here with masterly innovation (it took Schrader a couple of tries before he became a full-fledged “camera director,” and what he does with color and cutting here proves he’s reached the status of virtuoso), and yes, a form of grace that is hard-earned.