The movie opens with the flat, confiding voice of Tommy Lee Jones. He describes a teenage killer he once sent to the chair. The boy had killed his 14-year-old girlfriend. The papers described it as a crime of passion, “but he tolt me there weren’t nothin’ passionate about it. Said he’d been fixin’ to kill someone for as long as he could remember. Said if I let him out of there, he’d kill somebody again. Said he was goin’ to hell. Reckoned he’d be there in about 15 minutes.”

These words sounded verbatim to me from No Country for Old Men, the novel by Cormac McCarthy, but I find they are not quite. And their impact has been improved upon in the delivery. When I get the DVD of this film, I will listen to that stretch of narration several times; Jones delivers it with a vocal precision and contained emotion that is extraordinary, and it sets up the entire film, which regards a completely evil man with wonderment, as if astonished that that such a merciless creature could exist.

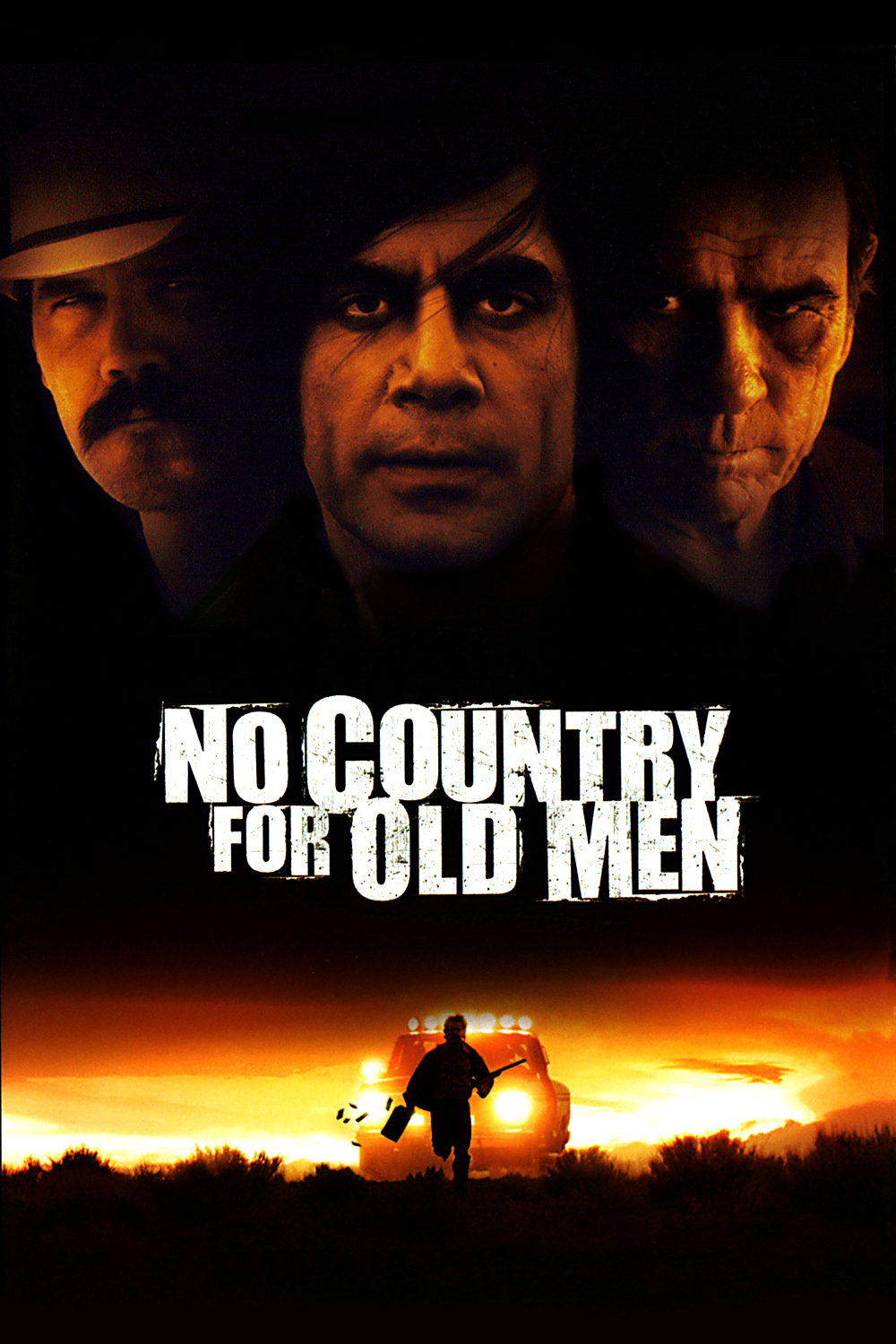

The man is named Anton Chigurh. No, I don’t know how his last name is pronounced. Like many of the words McCarthy uses, particularly in his masterpiece Suttree, I think it is employed like an architectural detail: The point is not how it sounds or what it means, but the brushstroke it adds to the sentence. Chigurh (Javier Bardem) is a tall, slouching man with lank, black hair and a terrifying smile, who travels through Texas carrying a tank of compressed air and killing people with a cattle stungun. It propels a cylinder into their heads and whips it back again.

Chigurh is one strand in the twisted plot. Ed Tom Bell, the sheriff played by Jones, is another. The third major player is Llewelyn Moss (Josh Brolin), a poor man who lives with his wife in a house trailer, and one day, while hunting, comes across a drug deal gone wrong in the desert. Vehicles range in a circle like an old wagon train. Almost everyone on the scene is dead. They even shot the dog. In the back of one pickup are neatly stacked bags of drugs. Llewelyn realizes one thing is missing: the money. He finds it in a briefcase next to a man who made it as far as a shade tree before dying.

The plot will involve Moss attempting to make this $2 million his own, Chigurh trying to take it away from him and Sheriff Bell trying to interrupt Chigurh’s ruthless murder trail. We will also meet Moss’ childlike wife, Carla Jean (Kelly MacDonald); a cocky bounty hunter named Carson Wells (Woody Harrelson); the businessman (Stephen Root) who hires Carson to track the money after investing in the drug deal, and a series of hotel and store clerks who are unlucky enough to meet Chigurh.

“No Country for Old Men” is as good a film as the Coen brothers, Joel and Ethan, have ever made, and they made “Fargo.” It involves elements of the thriller and the chase but is essentially a character study, an examination of how its people meet and deal with a man so bad, cruel and unfeeling that there is simply no comprehending him. Chigurh is so evil, he is almost funny sometimes. “He has his principles,” says the bounty hunter, who has knowledge of him.

Consider another scene in which the dialogue is as good as any you will hear this year. Chigurh enters a rundown gas station in the middle of wilderness and begins to play a word game with the old man (Gene Jones) behind the cash register, who becomes very nervous. It is clear they are talking about whether Chigurh will kill him. Chigurh has by no means made up his mind. Without explaining why, he asks the man to call the flip of a coin. Listen to what they say, how they say it, how they imply the stakes. Listen to their timing. You want to applaud the writing, which comes from the Coen brothers, out of McCarthy.

The $2 million turns out to be easier to obtain than to keep. Moss tries hiding in obscure hotels. Scenes are meticulously constructed in which each man knows the other is nearby. Moss can run but he can’t hide. Chigurh always tracks him down. He shadows him like his doom, never hurrying, always moving at the same measured pace, like a pursuer in a nightmare.

This movie is a masterful evocation of time, place, character, moral choices, immoral certainties, human nature and fate. It is also, in the photography by Roger Deakins, the editing by the Coens and the music by Carter Burwell, startlingly beautiful, stark and lonely. As McCarthy does with the Judge, the hairless exterminator in his “Blood Meridian” (Ridley Scott’s next film), and as in his “Suttree,” especially in the scene where the riverbank caves in, the movie demonstrates how pitiful ordinary human feelings are in the face of implacable injustice. The movie also loves some of its characters, and pities them, and has an ear for dialog not as it is spoken but as it is dreamed.

Many of the scenes in “No Country for Old Men” are so flawlessly constructed that you want them to simply continue, and yet they create an emotional suction drawing you to the next scene. Another movie that made me feel that way was “Fargo.” To make one such film is a miracle. Here is another.

* * * * Read more and contribute to the discussion at Scanners, here:

http://tinyurl.com/2zjc7l