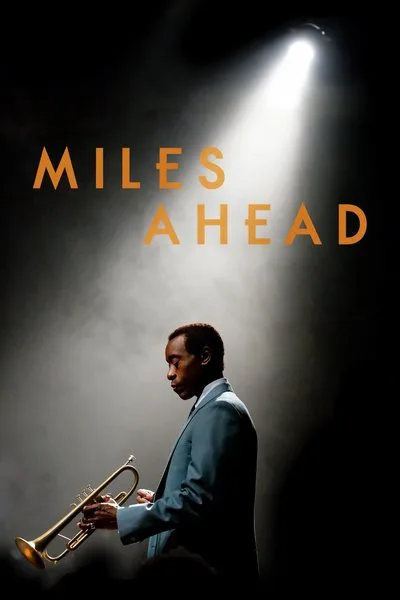

“Miles Ahead” is a film of ugly, bold bravado. Images move in and out of focus, at times without reason. The camera often sits in unexpected places—down an alley near the dumpster, languidly careening from one person’s mouth to another during a conversation, holding onto the corner of a face. There are so many textures and sounds and colors to the film—sheened afros, silk the color of ocean water and crimson, supple dark brown skin, glimmering diamonds, blood marring the collar of a crisp tan shirt, unhinged laughter—it veers toward sensory overload. It’s this impressionistic flavor that gives the film its crackling, memorable energy. But the moment that got under my skin is perhaps the quietest one in the film. It’s the aftermath of a fight between Miles Davis (Don Cheadle) and his wife/muse, Frances Taylor (Emayatzy Corinealdi). She wakes up in bed to find a pile of gifts lying next to her—fine furs, dresses, and glimmering jewels. Miles can’t (or won’t) see it when he comes behind her to place the diamond and ruby necklace around her neck but her face looks like a seam about to split. The jewels seem less beautiful when you realize they’re in memory of wounds Miles has inflicted. The look of pained yearning across Frances’ face communicates their marriage is doomed more than any moment prior.

“Miles Ahead” could have easily become a piece of treacly hagiography, more caught up in black cool rather than the suffering that underscores it. It’s to Don Cheadle’s credit—who not only stars as Miles but directed, produced, and co-wrote the film—that he doesn’t fall into the trap that far too many biopics do where the actor is so caught up worshiping the legend they’re playing that they can’t see them for the complicated, at times even vile, human beings they really are.

Cheadle chooses to eschew many expectations by zeroing in on Miles’ fallow period in the late 1970s and providing surprising flashbacks that jolt us through his past. When we meet Miles, he’s a ragged sketch of a man. He’s falling apart even though his bravado could fool you otherwise, at least for a moment. The framing device involves Miles interviewed by Dave (Ewan McGregor), a Rolling Stone reporter eager to find out what Miles has been up to during the years of his absence. Dave quickly gets swept up in the chaotic world of his subject, who just as quickly turns his discerning gaze on him as he does himself. The main plot involves a mysterious session tape that Miles’ record company is eager to get their hands on. The tape entices a slimy manager, Harper Hamilton (Michael Stuhlbarg), entwined in the proceedings, who tries to use it to boost the career of his incredibly talented, junkie client, Junior (Keith Stanfield). This plotline and Dave’s entire existence is pure fiction. None of this should work, but the mix of unexpected humor, genuine pathos, and bristling energy is enough to forgive the 1970s plot thread for its faults. Biopics work best when not focusing on the minutiae of fidelity but on the emotional truths of their subjects.

Cheadle’s performance is pure elegant vulgarity. He curses as if he is speaking poetry. He carries himself like a man who has lived a thousand lives. He cares less about Miles’ cool than he does about the tragedies he’s inflicted upon himself and others. The way he cares for the man is evident in his performance by the honesty that comes with each moment, whether it be Miles whipping out a gun in Columbia Records or asking Frances to marry him as two naked women lie in his bed in the next room. The performance echoes his work as Mouse in the neo-noir “Devil in a Blue Dress” but there’s more pathos and craft here. Cheadle keenly understands the darkness of Miles but doesn’t condescend. Instead he presents all his contradictions and guises—the addict, the sharply dressed genius, the madman, the lover, the unfaithful yet loving husband.

The film finds a sense of balance through a few great supporting performances. McGregor brings an engaging levity to the proceedings and creates a comfortable rapport with Cheadle. The push and pull between them is the stuff of legendary buddy/cop dynamics. As Junior, who feels like a curious mirror to Miles, Stanfield has some standout moments that deliver on the promise he presented in “Short Term 12.” But if the Miles/Dave dynamic was all there was to the film. it would be a fun, occasionally astute, creative piece of work but it wouldn’t be wholly memorable beyond the performances. The film finds its true emotional epicenter when it pivots back to the past, focusing on the courtship (then troubled marriage) between Miles and Frances.

Frances doesn’t appear in any of present day scenes except when fantasy and reality crash into one another and he sees an image of her which shouldn’t be in his home or hears her voice as if she is coming around the corner. She’s the wound of his past he can not stitch; a ghost appearing when he least expects it. Muses aren’t wholly people or at least they’re rarely allowed to be. So often in the biopics of artists, their muse figures feel less like wholly realized women and more like myths. When two artists get into a relationship, particularly a heterosexual one, only one tends to remain the creative. The other becomes caretaker, lover, muse, a tabula rasa to be reflected on, a source of energy to be drained. When Miles meets Frances she’s a dancer of incredible grace. We don’t get their marriage chronologically instead we chart the downfall of their love affair as if moving through memory. The past and present bleed onto each other. A word or sound causes Miles’ reverie to pivot to his wedding day or the night he’s so delirious after surgery he imagines that Frances is cheating on him and grows unhinged in his abuse.

Frances is a role that could easily be a shrill punchline, an empty emblem to show Miles’ issues. But Corinealdi is too assured an actress with too strong a presence to be sidelined. Cheadle’s performance, which is perhaps the best of his career, or at least the most inventive, could easily subsume hers. Miles is like the sun pulling everyone into his orbit, or, more aptly, a black hole few escape. But Corinealdi emboldens Frances with an intelligence and steeliness that is hard to ignore. She easily holds her own against Cheadle even stealing a few scenes from him in the process. I want to revisit the film again and again to study the way she uses her body, voice, and gaze to create such a beautifully realized performance. With just the slow drag of a cigarette or downcast eye, she communicates an entire history.

In the scenes of their courtship, there are moments of startling beauty seeing these two dark-skinned actors beautifully lit, creating and inspiring each other; falling in love. Part of the beauty is in how rare such an image is of two dark-skinned black artists given humanity. But the Eden they create for each other is short-lived. As their relationship grows more intense, he doesn’t change his ways but expects her to. After being beaten by white cops and spending a few hours in jail, the couple is back to the comfort of their own home. She tenderly bathes him. It’s then he asks her to give up dancing for good, as if he role as his wife is enough to feed her soul. Frances reels back in disgust and anger. But she eventually agrees. It’s a decision she comes to regret.

It’s also a mistake I’ve seen many women make. Eventually the weight of Miles’ faults become too heavy for even Frances’ love to bear. The story of their love and the artist/muse dynamic that underscores it could be a film on its own, perhaps even a better one than what we got.

As a director, Cheadle is able to deftly shift between time periods, moods, music and tones. The lush cinematography, inventive editing, which is more interested in capturing emotion than outright clarity, and crackling energy makes this film less a biopic and more a poem in motion about one of the most important American artists of the last one hundred years. It does justice to Miles Davis by turning a light into the darkest corners of his soul while still giving him added complexity with dashes of lurid humor and the flashbacks that show him at better times.

Still, “Miles Ahead” unravels at the end under the weight of the frankly ridiculous main narrative about the session tape. There’s one too many fired guns, car chases, overcooked moments overloaded with machismo, and bloodied fist for it to stay grounded emotionally. But there is a quiet brilliance to the film that left me electrified, inspired, challenged like all great films should. It doesn’t wholly work, but when it does it sings.