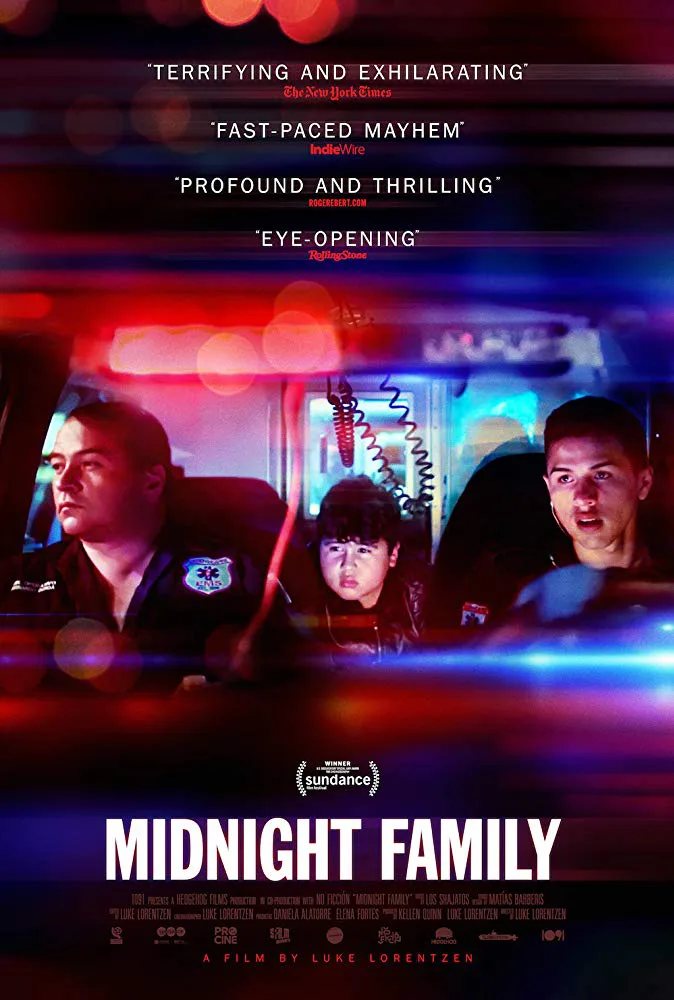

The night comes alive in “Midnight Family,” Luke Lorentzen’s film about a private ambulance service in Mexico City. This is one of the great contemporary films about the look and feel of a big city after dark, luxuriating in the vastness of almost-empty avenues lit by buzzing streetlamps. It’s a real-life answer to fiction movies like “Taxi Driver,” “Bringing Out the Dead,” “Collateral,” “Nightcrawler” and “The Sweet Smell of Success.”

And yet, despite the film’s careful attention to images and sounds—which is somewhat unusual in nonfiction, a mode that too often relies on verbal summaries, infographics, and talking heads—Lorentzen never allows “Midnight Family” to become an empty stylistic exercise. He stays tightly focused on his main characters, the Ochoa family, as they scramble to survive in a brutal, unregulated economy.

The Ochoas live and work in a city with nine million people but only 45 government-operated ambulances. Their ambulance is nominally run by a father, Fer, who has health problems and seems profoundly depressed (some of the film’s most haunting images are silent closeups of his face lost in thought). But the real boss is Fer’s 17-year old son Juan, who usually takes the lead in treating patients, dealing with finances and official regulations, and arguing with cops who hassle them in hopes of shaking loose a bribe. Juan also acts as an adjunct father to his little brother Josué, who gets frustrated at their hard existence (there’s an argument over how many cans of tuna they can afford to buy) but would rather be on the job with his family than attend school.

It’s a rough life. The Ochoas seem to live in the ambulance more so than in their small, cluttered apartment. A lot of the Ochoas’ patients can’t or won’t pay them for their labor. They must compete with other ambulance services to get to a scene first, even street-racing a rival in a sequence that’s reminiscent of the moment in “Gangs of New York” where the crews of two private fire trucks brawl in front of a burning house. Every month is a financial crap shoot.

The filmmaker, who shot and edited the movie in addition to directing and producing it, seems to have taken his cues from an earlier era of documentary cinema, represented by directors like the Maysles Brothers (“Salesman,” “Gimme Shelter“) and D.A. Pennebaker (“Don't Look Back“). The movie captures moments of astonishing intimacy, not just with the Ochoas but with their patients, the police, and the citizens they interact with from moment to moment. The camera looks at people and places and lets us think and feel things, rather than constantly and clumsily trying to manage our reactions.

There’s implicit criticism of government ineptitude and corruption and the viciousness of profit-driven life, particularly when it comes to healthcare, but these concerns emerge organically from the situations the director shows us. The tone is empathetic but clear-eyed, presenting the world’s indifference to struggle and suffering as a hard fact, as immutable as the winter draft that chills the interior of the ambulance until Juan asks his dad to shut the doors.

There’s no music. The movie doesn’t need it. It has traffic sounds, barking dogs, roaring auto engines and squealing tires, and the screams of injured people nearly drowning out the reassurances of paramedics trying to stop the bleeding. The sense of place is nearly overwhelming, and the editing finds little ways to re-emphasize it, such as holding on an empty room or ambulance interior for a beat or two after people have exited the frame. All the world’s a stage, we’re mere extras upon it, and there’s no way to know if anyone’s watching the play.