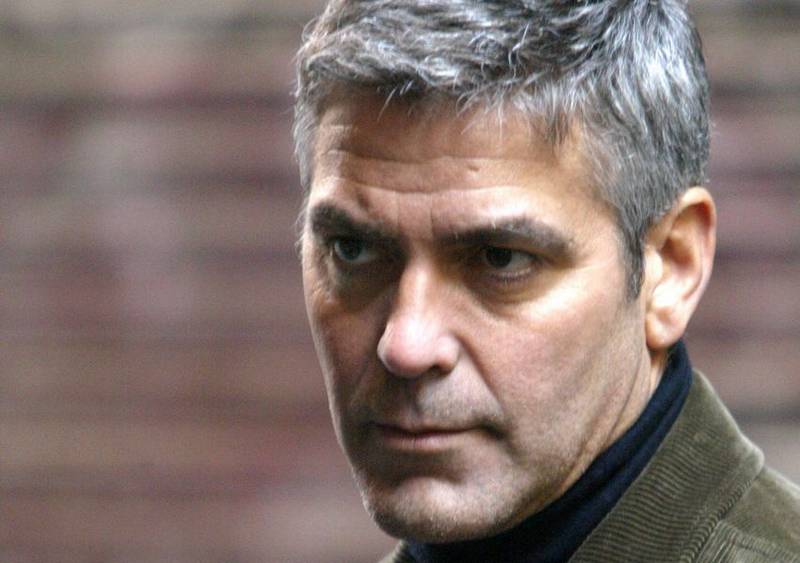

George Clooney brings a slick, ruthless force to the title role of “Michael Clayton,” playing a fixer for a powerful law firm. He works in the shadows, cleaning up messes, and he is a realist. He tells clients what they don’t want to hear. He shoots down their fantasies of “options.” One client complains bitterly that he was told Clayton was a miracle worker. “I’m not a miracle worker,” Clayton replies. “I’m a janitor.”

Clooney looks as if he stepped into the role from the cover of GQ. It’s the right look. Conservative suit, tasteful tie, clean shaven, every hair in place (except when things are going wrong, which is often). Drives a leased Mercedes. Divorced, drives his son to school, has him on Saturdays. Has a hidden side to his life. Looks prosperous, but lost his shirt on a failed restaurant and needs $75,000 or bad things might happen. Would certainly have $75,000 if he didn’t frequent a high-stakes poker game in a back room in Chinatown. Not much of a personal life.

Clayton works directly with Marty Bach (Sydney Pollack), the head of the law firm; it’s one of those Pollack performances that embodies authority, masculinity, intelligence and knowing the score. But one of Bach’s top partners has just gone berserk, stripping naked in Milwaukee during a deposition hearing and running through a parking lot in the snow. This is Arthur Edens (Tom Wilkinson), who opens the film with a desperate voiceover justifying himself to Michael.

The video of the deposition is not a pretty sight. One of the people watching it in horror is Karen Crowder, the chief legal executive for one of Marty Bach’s most important clients, a corporation being sued for poisonous pollution. Crowder is played by Tilda Swinton, who has been working a lot lately because of her sheer excellence; she has the same sleek grooming as Clayton, the power wardrobe, every hair in place. Thinking of Clooney, Pollack, Wilkinson and Swinton, you realize how much this film benefits from its casting. Switch out those four, and the energy and tension might evaporate.

The central reality of the story is that the corporation is guilty, it is being sued for billions, the law firm knows it is guilty, it is being paid millions to run the defense, and now Arthur Edens holds the smoking gun and it’s not quite all he’s holding when he runs naked through the parking lot.

Enough of the plot. Naming the film after Michael Clayton is an indication that the story centers on his life, his loyalties, his being just about fed up. Arthur Edens is a treasured friend of his, a bipolar victim who has stopped taking his pills and now glows with reckless zeal and conviction. We meet Clayton’s family, we get a sense of the corporate culture he inhabits, we sense how controlling the risks of other people sends him to the poker tables to create and confront his own risks as sort of an antidote.

The legal/business thriller genre has matured in the last 20 years, led by authors like John Grisham and actors like Michael Douglas. It involves high stakes, hidden guilt, desperation to contain information and mighty executives blindsided by gotcha! moments. We’re invited to be seduced by the designer offices, the clubs, the cars, the clothes, the drinks, the perfect corporate worlds in which sometimes only the rest room provides a safe haven.

I don’t know what vast significance “Michael Clayton” has (it involves deadly pollution but isn’t a message movie). But I know it is just about perfect as an exercise in the genre. I’ve seen it twice, and the second time, knowing everything that would happen, I found it just as fascinating because of how well it was all shown happening. It’s not about the destination but the journey, and when the stakes become so high that lives and corporations are on the table, it’s spellbinding to watch the Clooney and Swinton characters eye to eye, raising each other, both convinced that the other is bluffing.

The movie was written and directed by Tony Gilroy, son of the playwright Frank D. Gilroy (“The Subject Was Roses“). It’s a directing debut for Gilroy, who is a star screenwriter (all three Bourne pictures, “Extreme Measures” “Devil's Advocate” and “Proof Of Life“). As a first-time director, his taste runs toward the classical style and not toward the Bourne shaky-cam.

Working with the great cinematographer Robert Elswit (“Syriana,” “Good Night, and Good Luck,” “Magnolia“), he uses stable, brooding establishing shots, measured editing that underlines the tension in conversations, and lighting that separates the fluorescent sterility of Clayton’s business world from the warmth of family homes and the eerie quiet of a field at dawn. When he shows us Arthur Edens’ loft, it has the same sort of chain-link enclosure that Gene Hackman’s character had in “The Conversation,” and they are the same kinds of characters: paranoid, in possession of damaging evidence, not as well protected as they think.

The thing about Michael Clayton is he’s better at knowing how well protected they are, and what they think.