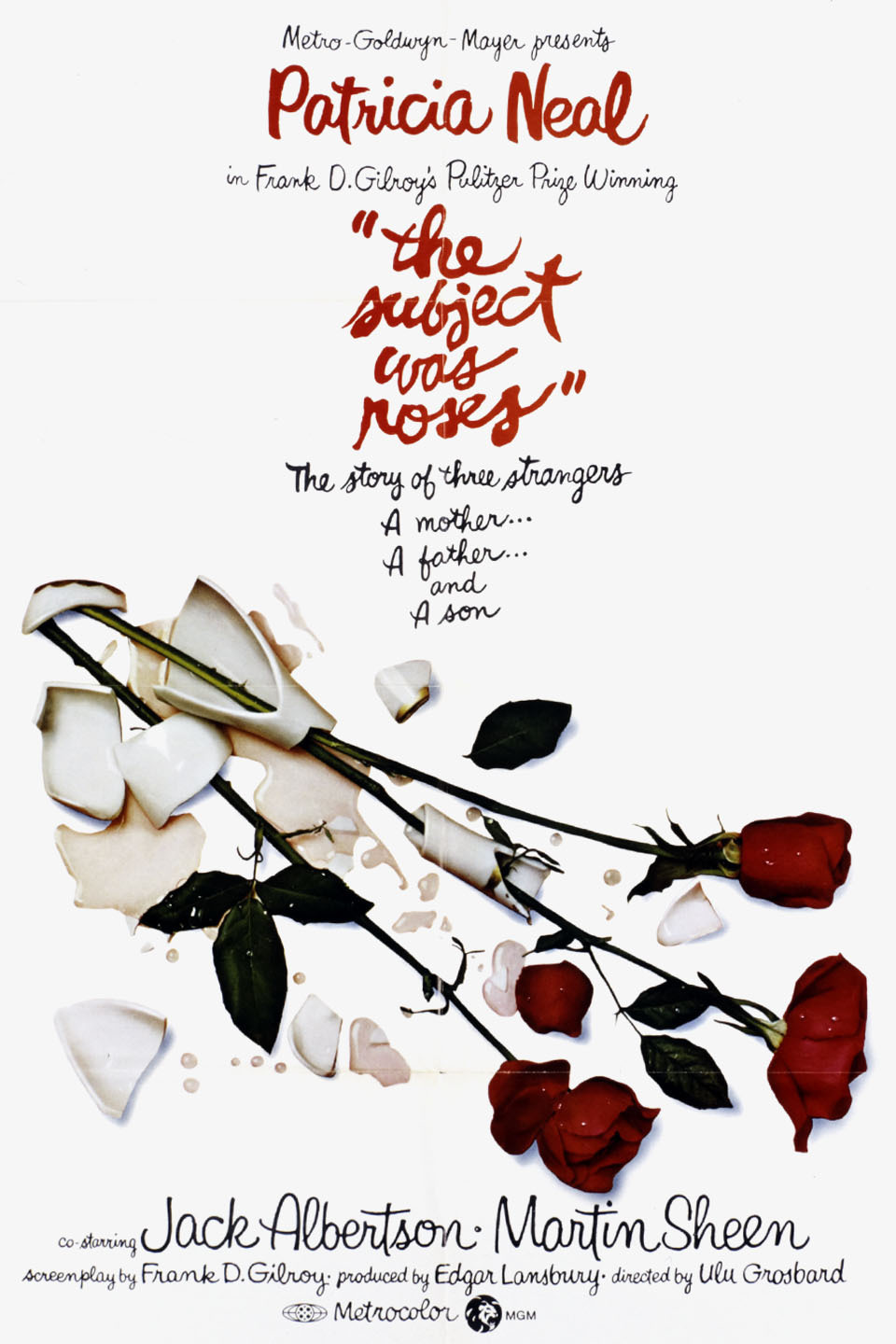

Frank Gilroy’s “The Subject Was Roses” was an extraordinary play, and it has been filmed with the greatest care, but it fails as a movie. It is hard to say exactly why. There’s nothing obviously wrong, but when you walk out you don’t feel as if you’ve been there. Something was missing.

The story has to do with a young man who comes home from the Army after World War II and finds himself caught in a crossfire between his parents. Their marriage has been in trouble for a long time, but now it arrives at a crisis because their son will no longer back down on the things he believes in.

The parents are wonderfully drawn portraits in Gilroy’s original play. We sense that sexual incompatibility is at the bottom of their quarrel, but they have branched out into a variety of battlefields: how to raise their son, money, the church, her family, suspected adultery and mutual persecution complexes. The typical American marriage, in other words.

All of these long-standing grievances come into the open when the son returns home and refuses to play the game. The three people are caged together in a lower-middle-class flat, and their struggle rages back and forth between the kitchen and the living room with occasional awkward sorties into the bedroom and the john. This material was suited to the limitations of the stage; the actors, like the characters, were trapped there and couldn’t do what they needed to most: bust loose.

Gilroy’s screenplay follows his original drama pretty much; the play is opened up to include a trip to a lakefront cottage by father and son, a night on the town by the whole family, and a Sunday when the mother unaccountably disappears and spends the day having lunch by herself and walking along the seashore. These openings allow director Ulu Grosbard to recreate effectively the feel of 1946: the cars, the fashions, the life-style.

But the heart of the film still remains in the apartment, and there it doesn’t quite work. Part of the problem is with the actors, I think. Jack Albertson, as the father, and Martin Sheen, as the son, are repeating roles they played on Broadway. Patricia Neal, as the mother, was cast directly for the movie. Albertson and Sheen are theatrical. They talk loudly, their movements are too obvious, they are trying to project. But in the movies the camera does the projecting and all the actor has to do is be there.

Miss Neal, who knows the movies, is better suited to the medium. She holds back, she suggests more than she reveals, and when all three actors are on camera her performance makes the other two look embarrassingly theatrical. And there is where the movie fails.

Because the story is about three people in the performerce TOGETHER — not separately as accomplished actors in their own right. And we do not; we cannot quite believe in scenes where the actors operate at different emotional levels. This may not seem like a very important objection, but remember the brilliant ensemble acting of Ralph Richardson, Jason Robards Jr., Katharine Hepburn and Dean Stockwell in “Long Day’s Journey into Night.”