That Stephen Sondheim and George Furth’s musical Merrily We Roll Along has stood the test of time is a sweet irony. Among other things, it’s a meditation on time itself.

The story was pulled from George S. Kaufman and Moss Hart’s 1934 play, which showed multiple friendships and romantic relationships forming and disintegrating as it moved backward in time rather than forward. The main plotline concerned a once-idealistic playwright who sold out his values and alienated those who loved him most. Flipping the chronology transformed what would have been a tragic slog into a bleakly funny autopsy of the characters’ life-altering mistakes. But audiences still rejected it, and it closed after six months.

The musical version fared no better, premiering in Fall 1981, and closing after 60 performances, 44 of which were previews. It was a humiliating failure for Sondheim, whose prior production was Sweeney Todd. Where Kaufman and Hart’s drama was undone mostly by the unwieldy scope of the production (there were 55 characters), the musical was doomed by its inability to make the story comprehensible for audiences whose ideal Broadway experience was A Chorus Line or Annie. Thirteen years later, Merrily mounted a much smaller production Off-Broadway. Every few years, somebody’s had another go at Merrily. Some of the productions had cuts, tweaks, and rewrites approved by Sondheim, even new songs.

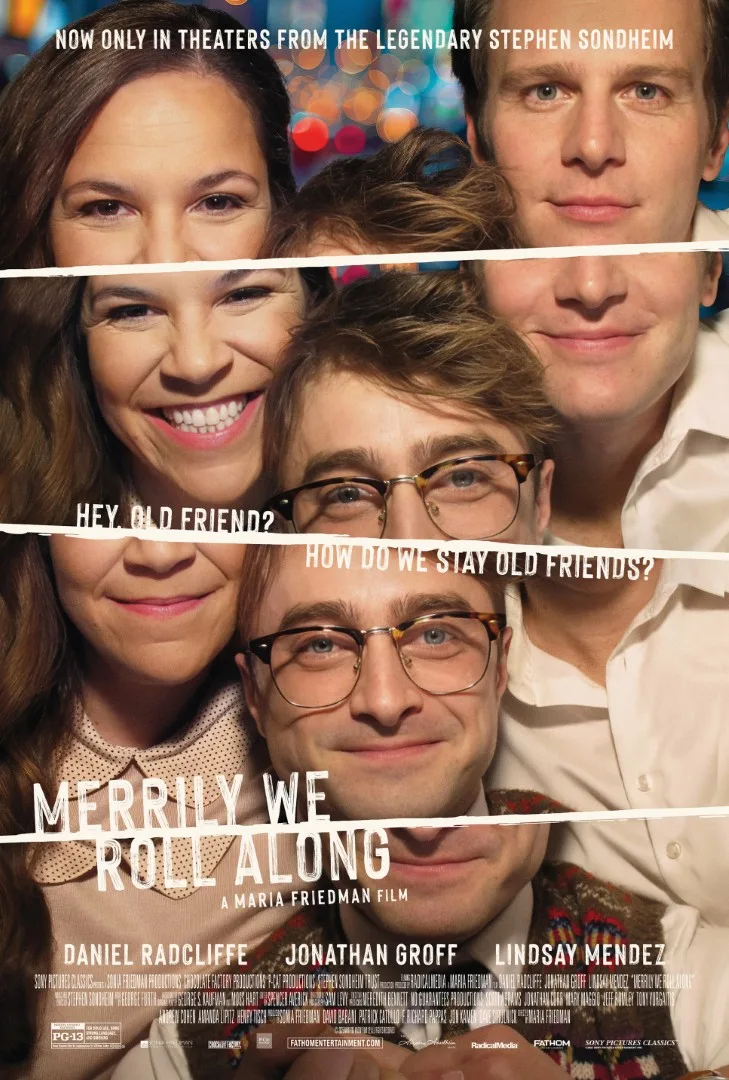

Forty years on, here’s a record of the 2023 Broadway revival directed by Maria Friedman, which many consider “Merrily We Roll Along” in its most evolved form. The production was captured in 2023 by a crew from RadicalMedia, which also did the 2020 “Hamilton” for Disney+. It showcases skillful acting and singing by the original cast and puts Sondheim’s imagination, playfulness, and mastery of composition and lyric writing on glorious display. Jonathan Groff stars as Frank Shepherd, a once-idealistic composer who achieved his biggest success as a producer of Hollywood blockbusters and left music behind. “Merrily” starts at what would usually be the end, celebrating his win at his mansion circa 1977 in the company of showbiz phonies he barely knows. The only exception, Mary, is the sole survivor of Frank’s gradual shedding of old ties, and has become an embittered alcoholic. She gives him a toast that’s really a kiss-off.

Daniel Radcliffe plays Frank’s onetime creative partner and best friend, Charlie Kringas, whose moral core is rock-solid. He’s not at the 1977 party. The next scene, set four years earlier, shows the event that precipitated the breakup. Charlie gradually soured on Frank’s ethical slipperiness and selfish acts, but only cut him loose after a 1973 talk show appearance during which Frank’s lucrative three-picture deal with a movie studio was publicly announced, to Charlie’s complete surprise. Frank not only made a deal that excluded his best buddy and chief collaborator, but also forced Charlie to find out about it on live TV in front of a studio audience.

Lindsay Mendez rounds out the central trio as Mary Flynn, a magazine writer. The three met on a New York City rooftop in 1957 while watching Sputnik’s orbit. The seeds of the trio’s great successes and painful failures originated on that rooftop, along with Charlie and Frank’s creative teamwork and Mary’s secret, unrequited love for Frank. Mary fell for Frank the instant after telling him she considered the ability to write music “the gift of gifts,” when Frank glanced at Charlie and deadpanned, “I’ve just met the girl I’m gonna marry,” a sentence that should not be uttered lightly. One of Frank’s unappealing qualities is his tendency to say things he doesn’t mean. Another is the way he walks over loved ones to get to the next milestone, then cranks up his charisma to repair the damage.

The main characters’ love lives are all disastrous, and patterned in ways that don’t repeat, exactly, but definitely rhyme. In 1977, Frank married singer-actress Gussie Carnegie (not her birth name, clearly), who flirted her way into a lead role in one of his productions. Krystal Joy Brown plays her as a young Eartha Kitt-style swanky kitten. Gussie used to be married to Frank and Charlie’s first and most important producer, Joe Josephson (Reg Rogers, who swaggers and stumbles and has an odd, wonderful gargle in his voice). Gussie left Joe for Frank, displacing Frank’s first wife, singer-actress Beth Shepherd (Katie Rose Clark), who used to be part of a trio with Frank and Charlie. Gussie storms the 1977 party and raises hell after learning Frank has taken a younger performer, Meg Kincaid (Talie Robinson), as his mistress. The order of Frank’s romantic partners is revealed as the film moves backward in time. By the time we get to Beth, we’re chuckling each time some new talented woman enters his field of vision, neither of them realizing what they’re in for.

You might’ve noticed that the verb tenses in this review are all over the place. That’s because it’s tricky to describe the architecture of a film that runs in the opposite direction from most, when American culture considers linear narrative “normal” and labels everything else pretentious. But it’s worth engaging anyway, because “abnormal” storytelling is mind-expanding. When Gussie throws iodine in Meg’s face at the 1977 party, it “foreshadows” Gussie spilling Chardonnay on Beth at a party in 1964, even though the 1964 drink-toss happened 13 years before the iodine attack.

When Charlie performs the song “Franklin Shepherd, Inc.” to lash out at Frank on the talk show, he’s one person re-enacting a more complex version of the number that we’ll see later, “Opening Doors.” Both numbers draw connections between instrumental and vocal music, spoken language, and ordinary sounds. And they treat typewriter keystrokes and piano notes, ringing telephones and carriage return bells, singing and humming, as instruments. Charlie has to do it all himself in “Franklin Shepherd, Inc.,” which takes place 18 years after “Opening Doors.”

Furth and Sondheim packed the book and music with tasty little bits that would be considered “foreshadowing” if the story didn’t run in reverse. In a standard chronology, low points that change the trajectory of characters’ lives would ideally produce surprise, and hopefully a burst of outrage or empathy. Here, they’re data that’s being added to a formal inquiry into how these people wandered so far from their youthful dreams. We smile at their misperceptions of which aspects of an era are fleeting and which are lasting, as when Mary tells Beth’s parents on Beth and Frank’s wedding day that she works for Look Magazine, a popular photo-driven publication that folded a few years later, and the mom replies, “Now there’s a steady, secure job!”

It’s also fun to realize that some scenes hit more or less the way they would have if the story had moved forward through time. In 1960, Frank, Charlie, and Beth wow customers in a beatnik cafe with their musical comedy revue about the Kennedy family. There’s an undertone of dread and sadness because we know what will become of Jack and Bobby, but we’d also feel that if we’d been moving in the opposite direction.

This is filmed theater in the purest sense. The direction and camerawork (by director of photography Sam Levy) start rough and scrambled, sometimes barely adequate, in the vein of a concert video you’d see on PBS during pledge drives, where the main goal is to show musicians making music and not miss any critical moments. Visually, things get tighter and more elegant as the story moves from the 1970s into the ‘60s and ‘50s. The narrative focus tightens as the number of significant characters shrinks, allowing the crew to devote more time and thought to each image. The fewer bodies onstage, the sharper the filmmaking becomes.

This was probably inevitable, considering that the production was trying to capture an actual event that happened in an actual theater, not break the story apart and rebuild it into a fully cinematic musical. The filmmakers were trapped between the proscenium and the fourth wall, so there were things they couldn’t do without losing the audience and tearing apart the sets. What’s onscreen represents a compromise between imagination and reality that evokes the “Opening Doors” number, where Joe pushes Frank and Charlie to make a show that’s more fun than demanding. “Give me a melody!” he cries. “Oh sure, I know/It’s not that kind of show/But can’t you have a score/That’s sort of in-between?”

Despite constraints, movie magic happens anyway. Minimalism is the crew’s best friend. The overture and first song, “Merrily We Roll Along”—which will recur in various arrangements—are built around tight closeups of Groff’s face, which manages to seem both haunted and oddly hopeful. Other characters’ lines are sung from beyond the frame line, or by performers who briefly pass through the background or remain out of focus. This makes us feel that we’re inside Frank’s head as he thinks about how he got here. The second-to-last and last numbers are the best. Both have just four characters. The shots are simple and uncluttered but forceful. The cutting from one shot to the next has a percussive effect that complements Sondheim’s lyrics, which dance as fast as they can.

The sum total is Frank’s philosophy of song, represented with moving pictures: “Writing music is not about words. Writing music is about sounds and feelings.”