If smart dumb comedies hold a place in your heart, you’ll like “Masterminds.” The main characters are masterminds only in their own heads, and the thoughts that tumble out of their mouths are as nonsensical as they are sincere. The stupider the thought, the harder the joke lands. “The Jerk,” “Napoleon Dynamite,” “Dumb and Dumber,” “Anchorman” and other films all worked this vein. There’s a whole glorious wing of smart-dumb that sends up crime pictures; the subgenre’s peak practitioners are probably Joel and Ethan Coen, whose filmography is packed with dunderheaded crooks who can barely tie their shoes, yet fancy themselves geniuses.

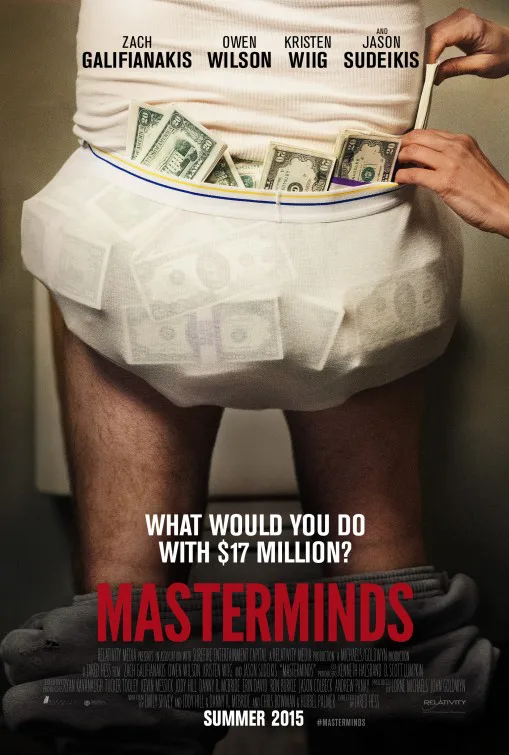

The Coens’ early masterpiece “Raizing Arizona”—the first of many botched kidnapping flicks by the Coens—looms over “Masterminds,” a polished bit of silliness about a band of small-time South Carolina crooks who somehow pulled off the biggest cash heist in American history: the inside-job robbery of an armored car filled with $17 million in Loomis Fargo money. I didn’t know any of the details of the actual case going in and was startled to learn that aside from the film’s goofy finale—which I won’t describe in detail because it’s terrific—a lot of the events that you’d assume were invented are drawn straight from life.

Of course all of those real details have been exaggerated and made grotesque or ludicrous, in manner of most “Saturday Night Live”-style, semi-improvised comedies; and many more incidents have been invented or embellished, the better to enable costars Zach Galifianakis, Kristen Wiig, Kate McKinnon, Jason Sudeikis, Owen Wilson and Leslie Jones to don wigs and facial appliances and trot out accents. In the end this is a film about dopes falling down, running into things, walking or running strangely, making sincere or “menacing” speeches that come out as word salad, and indulging in tender, even heartfelt exchanges that could have just as easily popped out of the mouths of Stan Laurel and Oliver Hardy.

The film’s crackpot-innocent sensibility is encapsulated by a scene where Wiig’s character Kelly Campbell, a former security company employee who was fired for incompetence, tries to convince an ex-coworker, Galfianakis’ David Scott Ghantt, that she’ll join him in Rio if he uses his keys to open a vault and steal cash from the company. David sheepishly replies that not only has he never traveled outside the country, he’s only been to the airport a few times. “It’s a magical place,” Kelly says, referring to Rio. “Yeah,” David says, “all those planes landin’ and takin’ off and such.”

David is sweet on Kelly, so he lets her entice him into meeting with the alleged mastermind of the heist, her friend Steve Chambers (Wilson), a pea-brain who dubs himself Geppetto because he’s “the guy pulling the strings.” David sheepishly corrects him: he’s thinking of another character from “Pinocchio,” Stromboli; Geppetto is actually the guy who built Pinocchio. You can tell by the way Steve tenses the back of his shoulders and neck that he hates being corrected. You can’t see his face, though, because they’re in a diner, and Steve is sitting one booth away with his back turned so David can’t identify him.

“Masterminds” was written by Chris Bowman, Hubbell Palmer and Emily Spivey and directed by “Napoleon Dynamite” and “Gentlemen Broncos” filmmaker Jared Hess, American cinema’s second most distinguished practitioner of smart-stupid comedy after the Coens. This film is much bigger, broader and lighter than his usual and lacks his characteristic molasses-slow buildups and a certain spiritual quality; but visually and tonally it’s in his wheelhouse. Most of the time in these kinds of films the notes of sweetness, naivete and regret feel forced, or else they don’t mesh with the sorts of whopping sight gags that Hess stages here, including a mercifully brief explosion of diarrhea, a Buster Keaton-styled car chase through a Mexican town, and an extended scene of David loading the armored car with purloined money, making a series of stupid mistakes that jeopardize the operation.

Here, though, you believe the sweetness, because Hess and his cast sell it with poker faces. Kelly is a femme fatale of sorts, but because she doesn’t grasp the full extent of the damage she’s inflicted on David’s life, you don’t hate her; you just wait for the inevitable moment when she feels bad and tries to set things right. David, likewise, can’t stay a schlub forever, even though he never realizes that his bangs, mustache and beard make him look like a Muppet. (He thinks everyone else looks ridiculous, at one point describing Steve as “Ric Flair’s little boy.”) You know he’ll stand up and fight back at some point, and that when it does, it feels like an earned redemption rather than a plot obligation. Sudeikis’ character, a hitman hired to kill David to stop him from spilling the beans to Jones’ FBI agent, has an even stranger, bizarrely moving arc, one that I wouldn’t dream of revealing here.

The film is probably too long and sometimes too pleased with itself, and the structure and pacing are frustrating; not bad, just frustrating, because they prevent “Masterminds” from becoming truly excellent instead of consistently amusing and occasionally inspired. And it needed a lot more of McKinnon, whose scene-stealing turn as David’s jilted fiance captures a particular type of mirthless optimist with spooky accuracy. (She’s always announcing deep feelings through a set jaw, dead doll eyes flashing.)

Still, there’s something inspiring about so many talented physical comics throwing themselves into roles that have moments of true emotion as well as countless opportunities to yammer, pratfall, bellow in rage, and thrash each other with whatever objects are in reach. Throughout, the movie keeps serving up grace notes that make the whole experience richer: Kelly soothing David on the phone by singing him tuneless vocal runs; a slow-motion shot of David strutting in a caballero outfit while clutching an elephant pinata; Sudeikis’ assassin leaving a pile of cash for a friend and placing a tiny black sombrero on top of it like a paperweight. Another of David’s blithering declarations of love for Kelly should’ve been the movie’s tagline: “Bonnie needs his Clyde.”