“Tatami” feels both new and old. It’s a sports drama shot in black and white that tells more or less the same story as one of those old Hollywood thrillers about gangsters pressuring a boxer to throw a fight. Here, though, the boxer is the most talented judoka on the Iranian women’s national judo team, and the gangsters are the Iranian government, who won’t let their athletes compete against Israelis because to do so would contradict Iran’s position that Israel is not a state. The result is a superb example of pop cultural translation that freshens up the clichés of the sports corruption thriller and gives the actors and filmmakers a chance to flex their considerable skills. Along the way, “Tatami” serves to chastise governments that use sports as a continuation of politics by other means.

“Tatami” begins with a shot of the team on a bus, headed for Tbilisi, Georgia, where Iran’s women’s judo team is set to compete in a match against other national teams in hopes of bringing home a gold medal. The top judoka is Leila (Arienne Mandi), a driven, stubborn, brilliant athlete whose main competition for the gold medal is an Israeli. Back home in Tehran, Leila has a loving and supportive husband, Nadeh (Ash Goldeh), and two children. Every time she competes, the extended family gathers to watch the matches on TV. Leila’s coach and close friend is Maryam (Zar Amir Ebrahimi), a former judoka whom Leila idolized as a child. Leila arrives in Tbilisi with every intention of steamrolling the competition and proving herself the best in the world. But life has other plans.

The story takes place almost exclusively in the sports complex in Tbilisi and Tehran, where the judo association is under increasing pressure from the Supreme Leader’s office to convince Leila and Maryam to fake an injury as a cover story for avoiding a face-off with the Israelis. The pressure is conveyed through a series of increasingly belligerent phone calls to Maryam, who is expected to persuade Leila to prioritize her country’s political interests over her desire for personal recognition.

The film’s title works on multiple levels. Tatami are the mattresses that cover the floor of the dojos where fighters compete. This is a movie about the different types of arenas in which battles are fought. In addition to the one where Leila and her opponents grapple, there’s a geopolitical arena in which athletes are treated as proxy soldiers in an ideological war. There’s another arena, too: the ones inside the main characters’ heads, which ideally should be filled with nothing but the pure drive to excel. Running beneath the plot is a quiet lament for the impossibility of sports existing on their own terms, for their own sake.

The movie’s very existence is a repudiation of the notion that national identities should interfere with athletes’ pure motivation to win. Fittingly, the filmmakers are a duo that wouldn’t be allowed to face each other as athletes: Guy Nattiv, an Israeli, and Ebrahimi, an acclaimed French Iranian actress and filmmaker who produced the movie in addition to costarring in it, and who left Iran almost twenty years ago. The script is by Nattiv and actor-writer Elham Erfani, who is also French-Iranian. The movie was not shot in Iran because movies that directly criticize the Iranian government tend to land the filmmakers in jail.

“Tatami” is not an artistically immaculate work. Once it gets past the halfway point, the alternation of judo and behind-the-scenes political maneuvering becomes repetitive (there may be one too many matches en route to the finale). There are also some flashbacks to Leila’s home life that don’t appear until the nerve-wracking final section of the movie, which feels like the wrong place for them, if indeed they were necessary. I’m not convinced that they were. “Tatami” is at its best when it’s showing us the actions of the heroine, her coach, and the various supporting characters (including International Judo Federation administrators on-site who get wind of what’s happening to Leila and discuss if and how to get involved).

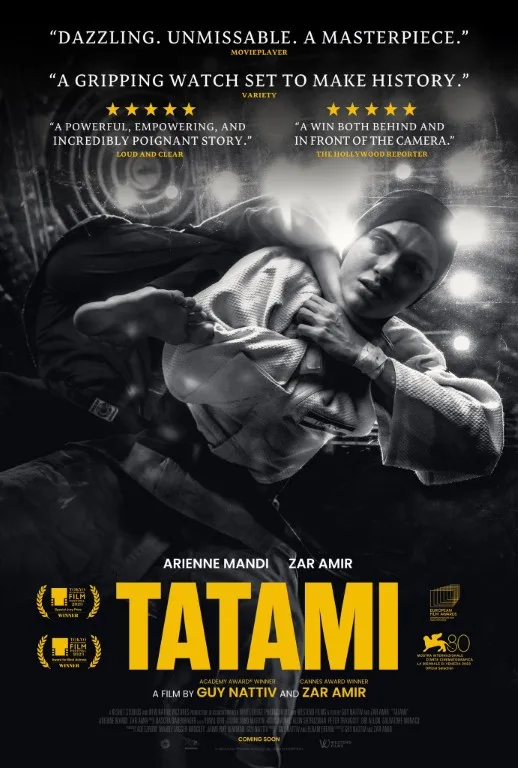

But these are minor misgivings about an otherwise engrossing and propulsive movie. The black-and-white imagery, by cinematographer Todd Martin, is a striking modern reintegration of the visual language of sports dramas from an earlier time, specifically the subcategory known as “boxing noir,” where monochrome meets big shadows and exaggerated perspectives. “The Set-Up,” “The Harder They Fall,” “Killer’s Kiss,” and “Body and Soul” all operate in this zone. So do self-conscious and film history-aware movies like “Raging Bull,” which was more about moral and spiritual corruption than boxing per se. “Raging Bull” is probably the major touchstone here. It’s fascinating to see a source that (like nearly all Scorsese films) is so unabashedly fascinated by concepts of masculinity being channeled into a movie about women whose already precarious identities in sports, which is still mainly thought of man’s world, are rattled by the bullying of a patriarchal society rooted in fundamentalist theology. (The flashback that comes closest to pulling its narrative weight is one where Leila and her husband are in bed being intimate the night before the team leaves for Georgia, and a WJF official calls to make sure she has her husband’s permission to travel.)

This isn’t the kind of story that movies usually tell. Still, it’s one that should be told more often, considering the intellectual and emotional payoffs that accrue when the artists are all on the same page and are as accomplished at moviemaking as Leila is at judo. The premise is innately powerful and offers a lot of room to bring the world beyond the arena into the arena, expanding the horizon of the sports picture. There isn’t anyone anywhere who can’t relate to “Tatami” on some level, even if they’ve never competed in sports. The individual vs. the state is the ultimate one-sided contest.