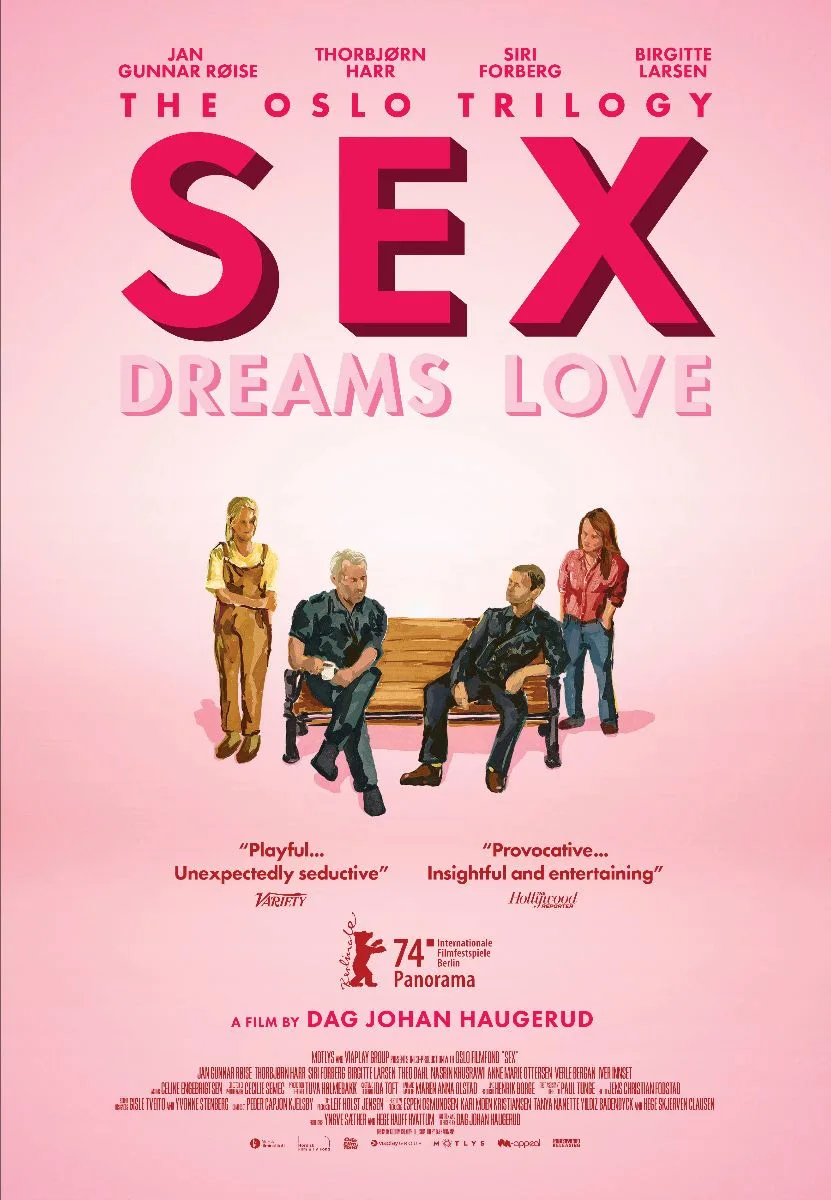

“Sex,” part of a trilogy by Norwegian author turned writer/director Dag Johan Haugerud, sometimes feels like a dramatized sermon. Divided into two storylines, “Sex” concerns a turning point in the lives of two questioning Oslo chimney sweeps, neither of whom is named in the movie. One man (Jan Gunnar Røise) confesses to his boss (Thorbjørn Harr) that he recently had a meaningless sexual encounter with a client, which is mainly noteworthy since the client (not in the movie) is a man. His boss counters by recalling a persistent dream where David Bowie approaches and looks at him as if he were a woman, whatever that means.

Most of “Sex” follows its two co-leads as they try to understand what, if anything, has changed for them. Dialogue does most of the heavy-lifting here, just like in “Love”, the first and most recently released entry of Haugerud’s thematically related series. Haugerud’s knack for visual storytelling also makes a difference, specifically in how he presents the city of Oslo and its features as an enriching backdrop. His eye for unflashy, humanizing details makes the best parts of “Sex” feel like a collection of mini-portraits. Unfortunately, “Sex” concludes without resolving its immediate conflicts. Instead, Haugerud’s protagonists and their loved ones preach to each other about how they think we, I mean we, should treat others. And then there’s a campy and unconvincing song-and-interpretive-dance number to sum everything up?

The didactic and allegorical nature of “Sex” is plain enough. However, the movie’s irresolute finale is still disappointing, as Haugerud essentially lets his two male leads drift away without considering the implications of their newfound queer thoughts. Harr’s character doesn’t seem to care if his dreams might be a sign that he might not be a man after all. Instead, Haugerud kicks that conversation down the road, along with the one that was started when Røise’s curious prole tells his wife (Siri Forberg) that he had a one-time fling with a stranger. Never mind if these self-fashioned straight men are or aren’t gay—that question exemplifies the sort of confining judgment that Haugerud asks viewers to abandon. It’s a noble sentiment, but not one that his tense, but unsatisfying drama can meaningfully sustain.

It may help to know that the Bowie-dreaming chimney sweep identifies as a Christian, and in more than one scene. One Night Stand thanks his colleague for being open enough to share his religious background. And Bowie Boss’s teenage son (Theo Dahl) notes that dad conveniently omits the religious parts of a choral hymn when he sings for a vocal coach (Nasrin Khusrawi) during a routine consultation. It seems that Dad worries he won’t be accepted if he shares his Christian background with others. This creates a convenient and largely unexamined parallel with his co-worker, who spends most of the movie trying to soothe and regain the confidence of Forberg’s shaken and sadly blinkered partner. It also places a rather heavy implication on the repeated suggestion, from his unaware wife (Brigitte Larsen), that the person in his dream sounds more like God than David Bowie.

A few dialogue-intensive scenes ostensibly set up an ending that we might not be ready for. But even these contextualizing scenes, including a detailed and intriguing story about a loving couple and a shoulder tattoo, are sadly light on conflict and incidental details. The people in Haugerud’s humanist drama are ultimately more like cyphers than flesh-and-blood people.

The best scenes in “Sex” are both emotionally complex and provocative, especially Røise and Forberg’s awkward, naturalistic, and very believable conversations about trust and desire. Her frank questions for him run the emotional gamut from sympathetic to absurd, like when she asks her partner, “Surely you can tell me if your *** was sore afterwards?” Some over-reaching dramatic moments can also be charming, like when Khusrawi paraphrases Hannah Arendt in a speech that effectively spells out the movie’s Utopian values.

That said, it’s hard to understand how a romantic drama about tolerance could be so tone-deaf and ungenerous once Haugerud inevitably ties together both stories. He conveys so much frustrated longing in a dialogue-free scene where Røise watches Forberg and two companions laugh and chat heedlessly at a city café. Haugerud also has one male lead console the other by mysteriously observing that, “You remember being penetrated. You can keep that to yourself. Treasure it in your heart, like the Virgin Mary.” Come again?

That line, along with the movie’s strained concluding musical performance, asks too much of viewers, no matter how sympathetic its underlying logic may be. You may still find “Sex” to be a good conversation-starter, if only as an excuse to ask your partner what they think about anal sex and the Virgin Mary.