The director of this movie, Alexandre Philippe, is obsessed with film and filmmaking AND filmmakers and always takes an interesting angle in his documentary examinations of them. His 2017 “78/52,” for instance, was an intense examination of the shower-murder scene in Alfred Hitchcock’s “Psycho”—90 minutes devoted to three minutes! The title of his 2010 “The People Vs. George Lucas” (in which your humble correspondent is interviewed) is self-explanatory. God knows he could make several sequels to that, but I imagine he regards that prospect with some dread, given how much more addled “Star Wars” fandom has grown in the intervening decade.

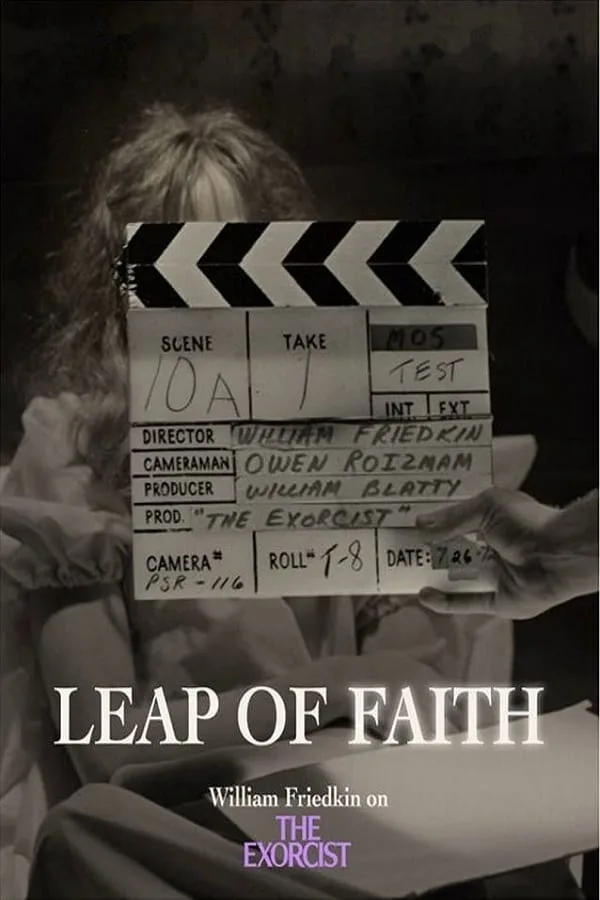

His new movie, “Leap of Faith: William Friedkin on ‘The Exorcist’” is also a simple proposition. As in the 2017 documentary “Friedkin Uncut,” directed by Francesco Zippel, the fulcrum of the piece is the presence of Friedkin himself. While Zippel incorporated outtakes of Friedkin waxing both dyspeptic and comedic to give a sense of the filmmaker’s still somewhat turbulent personality (here’s where Federal law requires that I point out that somebody in the 1970s nicknamed him “Hurricane Billy,” which I reckon had to be the kindest way to describe his volatility), Philippe depicts Friedkin in a way that mostly respects the fourth wall—there’s a moment when he allows footage of Friedkin addressing his director/interviewer directly, and when you see it you’ll understand why he let it stand—and gives the director seemingly free rein to describe all the ideas and art that informed the movie.

If you’ve read the great director’s memoir or seen him introducing his films at rep houses, you know that Friedkin, now 85, is operating in a kind of avuncular mode. An autodidact raised in poverty in Chicago, he is remarkably erudite in conversation, or “conversation,” and from the very beginning the correspondences he makes between the formation of his own aesthetic and the way “fate” conspired to lead him to direct “The Exorcist” are dazzling. After giving a sketch of his early life and how he was seduced by cinema (of course “Citizen Kane” features here), he speaks of film that shows true religious feeling, and brings up Carl Dreyer’s 1955 “Ordet,” a drama of faith redeemed, in a rather startling way. He then walks us through “Kane,” and what he believes is its New-Testament-derived message, “What should it profit a man if he should gain the whole world, and lose his own soul?” It’s thrilling when Friedkin’s words and Philippe’s adroitly placed film clips walk us through movie endings in the tradition of “Kane”: Kubrick’s “The Killing,” Huston’s “The Treasure of the Sierra Madre,” and Friedkin’s own “Sorcerer.”

Meticulously but also expansively, Friedkin goes through every aspect of the movie’s development and creation. His relationship with “Exorcist” author William Peter Blatty is fascinating. Blatty based the tortured Father Karras on himself, and according to Friedkin offered the director his own profit points on the film if Friedkin would allow Blatty to play the role. Friedkin discusses how a screen test by Jason Miller, then an acclaimed playwright but a complete nonentity in movie acting, convinced him to throw over the name actor who’d already been signed to play the role. Friedkin’s philosophy on film music, his approach to editing—“subliminal” cuts that are central to the movie’s shock effects and its thematic resonance—his shooting methods and the way great painting influences his approach to light; all this stuff is incredibly engaging, and buttressed perfectly by Philippe’s use of material from the film itself.

If anything makes one believe in “fate” the way Friedkin has come to, it would be in the story of how the director discovered Mike Oldfield’s “Tubular Bells” while casting around for the movie music. He barely knew what the music even was when he first heard it, but he knew he was looking for something in the line of a variant of Brahm’s “Lullaby.” When this movie shows the shot of Ellen Burstyn walking through Georgetown with Oldfield’s haunting theme accompanying, the absolute perfection of the combination is still breathtaking. And yet it was just something he stumbled upon. (And indeed, while Friedkin doesn’t discuss this, the music’s use in the movie made “Tubular Bells” a huge hit, and gave a real leg up to the entrepreneur on whose record label it was issued—a guy named Richard Branson.)

But the section on music also underscores what could be seen as a weakness in the movie. Friedkin goes over how he and the studio had commissioned a score from Lalo Schifrin, and how he felt the music from the composer wasn’t right. He mentions that he and Schifrin had been friends, and have not spoken since. If you’ve read Peter Biskind’s Easy Riders, Raging Bulls—and I should point out here that many of the people portrayed in that book about ‘70s Hollywood have balked, with extreme prejudice so to speak, at how they are portrayed in the book—you will have the distinct impression that at the time, Friedkin was not just less than diplomatic in conveying his differences to Schifrin, but downright abusive. (It’s not too late, Bill! Schifrin’s still alive, you can make an amends!)

You’ve probably also read or heard of lead actresses Ellen Burstyn and Linda Blair sustaining injuries on the set of that movie that affect them to this day. This documentary does not address any of that. I don’t know if Philippe just chose not to ask, or if there were preconditions set by Friedkin about going near those topics (and I’ve been there, so if that was the case, I get it). But anyway, it’s like the title says: this is Friedkin on the movie. And what he does have to say, after all this time and so many articles and movies touching on “The Exorcist,” is still engaging, fascinating, and entertaining.

Now available on Shudder.