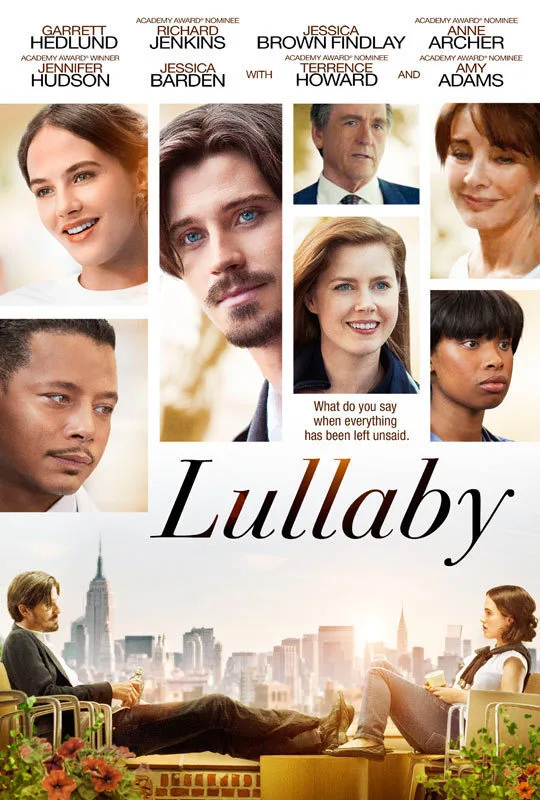

Garrett Hedlund slogs through what feels like the most eventful day in the history of cinema in the mawkish family drama “Lullaby.”

Hedlund leads a strong cast that mostly goes to waste in artist-turned-writer-director Andrew Levitas’ film about a wealthy clan coming together to witness the patriarch’s wish to die after a 12-year battle with cancer. Levitas’ tale is earnest and clearly very personal, inspired as it was by events within his own family. The subject of assisted suicide is certainly a polarizing one, and—in theory—a film like “Lullaby” should both enlighten and inspire debate. Instead, it feels simultaneously superficial and overbearing, albeit with a few moments that do indeed resonate.

At the film’s start, Hedlund’s character, the scruffily handsome Jonathan, is sneaking a cigarette in an airplane bathroom. He’s clearly a mess both physically and emotionally, but has retained enough traces of his charismatic former self that he successfully sweet-talks a flight attendant out of reporting his violation. This early scene actually does more to define his character than his actions throughout the rest of the film.

Like so many of Levitas’ characters, Jonathan is a cliché: a trust fund kid turned failed rock star turned aimless and cynical twentysomething. As he returns home to New York on a red eye from Los Angeles, he must reflect on his vague estrangement from his father, an esteemed financial wheeler-dealer played in flashbacks by a toupeed Richard Jenkins. In the present day, Jenkins’ efforts as the dying Robert Lowenstein represent the majority of the film’s emotional weight.

Being an actor of great nuance and versatility, Jenkins manages to convey a lot while in a tough spot. He’s lying in a hospital bed most of the time he’s on screen, but still finds the sly humor in his character—along with the remorse and the healing power of reconciliation—with just the slightest lift of an eyebrow or modulation of his voice. He definitely elevates the material beyond what’s on the page, and he finds subtlety where it’s mostly lacking.

Also gathered at Robert’s bedside are his loyal and weepy wife, Rachel (Anne Archer, stuck in a one-note role), and the couple’s aspiring-lawyer daughter, Karen (Jessica Brown Findlay), who has filed an injunction to prevent her father from taking himself off life support. Later, Robert will require Karen to present formal arguments against his plan in his sterile but spacious hospital room; this is meant to be a climax of sorts but instead feels distractingly stagey. Findlay (as the younger overachiever) and Hedlund (as the older disappointment) do enjoy one decent, middle-of-the-night bonding scene, but their characters still remain types.

Jonathan also finds time to trade quips with Jennifer Hudson as the obligatory sassy nurse who works day and night without any breaks because she serves as a crucial source of humor and the voice of reason. While Hudson’s character is clearly a device, Terrence Howard is given even less of a personality as Robert’s trusted physician, who’s willing to carry out his wishes. But Jonathan spends the majority of his time away from his father’s bedside, as the clock ticks down with two women who function even more as obvious, screenwriterly ideas than full-fledged people.

One is an ex-girlfriend of his—the one that got away, it seems—who happens to appear magically on any Manhattan street where she’s needed to stare wistfully into his eyes and remind him (and us) that he used to be a good guy. She’s played by a woefully underwritten Amy Adams in a mostly extraneous part. Even an actress of her caliber can only do so much with so little.

The other is even more of a device: a 17-year-old girl named Meredith who’s also dying of cancer in the same hospital. She’s played by Jessica Barden, and she’s even more magical than Adams’ character. She has wisdom beyond her years. She has perspective. She says just the right thing at just the right time to make Jonathan stop feeling sorry for himself. As they meet over surreptitious cigarettes in the hospital stairwell, Jonathan asks Meredith: “Are you even old enough to smoke?” The frail, hairless girl replies matter-of-factly: “Am I old enough to die?” in one of many examples of Levitas’ stilted dialogue.

Jonathan finds time to bond with all these people, plus attend a makeshift Passover Seder for his father, plus serve as Meredith’s date for the private prom that her fellow patients somehow whip up for her. Relationships that should take days if not weeks to form develop within a few hours; granted, the notion of time means something different to these people, but this is just dizzying and implausible.

But Levitas does take a while to wallow in the tear-jerking catharsis. It is lengthy, relentless and unabashed. He also finds a few moments for some obvious symbolism as a couple of characters spend time admiring the newborns at the hospital’s maternity ward.

It’s the circle of life. Someone should write a song about it. And wouldn’t you know? Jonathan does just that in one of the many endings “Lullaby” has to offer.