When the latest British Film Institute greatest-films-of-all-time poll came out a few years ago, it wasn’t terribly surprising that an Alfred Hitchcock film had displaced “Citizen Kane,” which had occupied the top spot for several decades. But why “Vertigo”? If the importance of Orson Welles’ classic had stemmed from the common view that it launched sound-era auteur cinema (especially in its influence on the young critics who would become the auteurs of the French New Wave), surely the Hitchcock film that had a similar game-changing impact was “Psycho.”

That thought may well cross the minds of viewers of “78/52,” which, in providing a detailed analysis of the shower scene in Hitchcock’s horror milestone, makes a persuasive case for “Psycho” as the film that jump-started modern cinema, not just in its startling fusion of sex and violence (which anticipated much about the ‘60s, off-screen as well as on) but also in a revolutionary use of film technique that would galvanize audiences and inspire filmmakers for decades to come.

While Alexandre O. Philippe’s film is essentially a big geek-out for cine-obsessives, it’s one that makes you realize that “Psycho” is not the property of a coterie. That shower scene may be the best-known movie sequence in modern cinema. Endlessly imitated and parodied (and even remade shot-by-shot by Gus Van Sant), it’s familiar material even to many casual movie fans as well as filmgoers generations removed from its shocking advent.

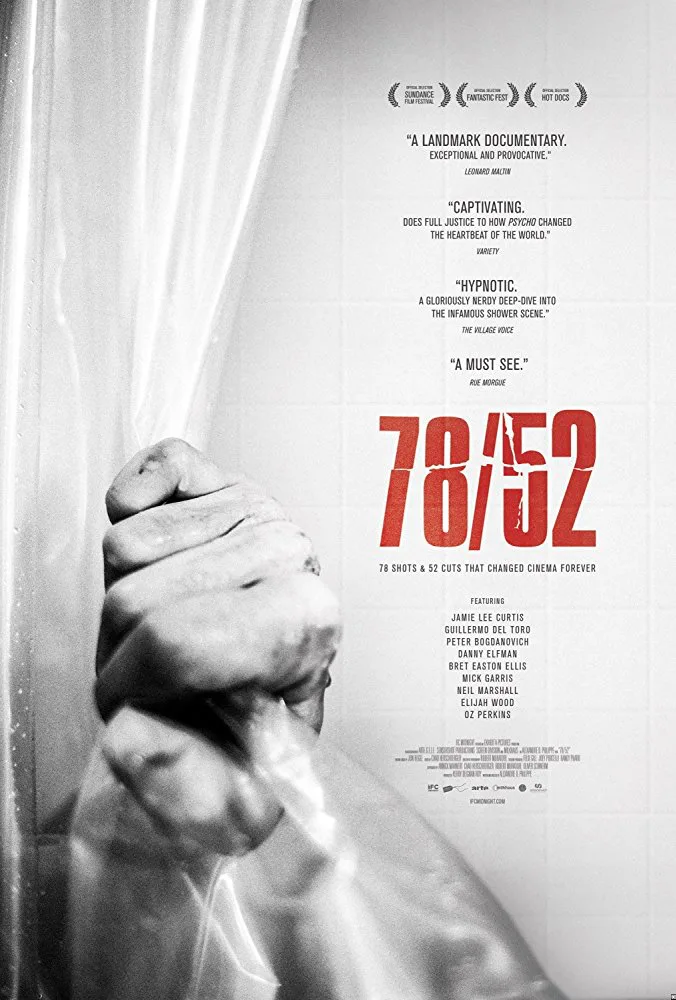

That familiarity means that many viewers of “78/52” (the title refers to the three-minute scene’s 78 camera set-ups and 52 cuts) will begin the film realizing they already know a lot about what’s being discussed. The virtue of Philippe’s approach is that it organizes an intelligent, analytic discussion that expands and deepens our knowledge by drawing upon commentary from the likes of Walter Murch, Peter Bogdanovich, Bret Easton Ellis, Eli Roth, Danny Elfman, Jamie Lee Curtis, Guillermo del Toro and others, plus vintage TV clips of Hitchcock interviews.

Some of the most fascinating testimony comes from Marli Renfro, a model (and sometime Playboy Bunny) who served as Janet Leigh’s body double in the shower scene. She recalls the scene’s lengthy shooting, in which she was topless and offered to remove the “crotch patch” she wore; Hitchcock declined.

Starting out, the film makes the point that the low-budget, black-and-white “Psycho” was a deliberate antithesis to the big, glossy, Technicolor star vehicles (such as “North by Northwest,” “Vertigo” and “Rear Window”) that made the 1950s Hitchcock’s most successful decade so far. For this viewer, though, one of the most thought-provoking bits of contextualizing here comes in connecting the movie’s theme of invaded spaces and unexpected attacks to the warnings that Hitchcock provided in films like “Foreign Correspondent” and “Lifeboat” of what he saw as the U.K. and U.S.’ lack of preparedness for World War II.

Although Philippe gives surprisingly little attention to how Hitchcock’s popular TV show influenced “Psycho,” he does note that when the movie was done, Hitchcock considered it such a flop that he considered editing it down to an hour and using it on TV. Composer Bernard Hermann convinced him to do otherwise, and gave him the legendary score that helped the shower scene elicits screams from coast to coast. Peter Bogdanovich recalls emerging from the movie’s first showing in New York feeling that he’d been “raped.”

Shot in black and white and generous in its use of clips from “Psycho” and other movies, “78/52” looks at virtually every aspect of the shower scene—including the staging, the production design, the music and sound effects, the camera work, Saul Bass’ storyboards, etc.—and marvels at how brilliantly integrated they were. The word “genius” is heard more than once, and the more the film shows us, the less even hardened skeptics will be likely to demur.

Some of the most fascinating bits concern details in “Psycho,” showing how even minor design elements in the movie contribute to its overall tapestry of meaning and emotion. There’s a discussion of the floral wallpaper in the Bates Motel, and a detailed analysis of why the Dutch painting of “Susannah and the Elders” that covers Norman Bates’ peephole was the perfect rendition to connect the Biblical theme to Norman’s state of mind.

Philippe’s interviewees also pay ample tribute to the subtle modulations in Anthony Perkins’ brilliant and haunting performance as Norman. No one, though, wonders if his casting might have had something to do his status as a closeted gay man whose biography contained a dead father and domineering mother (similar casting questions of course could be asked of other Hitchcock films including “Rope” and “Strangers on a Train”).

Perhaps unsurprisingly, there are no interviewees here who question the value of “Psycho” or its impact on the culture. That’s because it’s basically a fan’s film, of course. But it’s also testament to the power and mastery of a movie that, nearly 60 years on, still feels as modern, complex and cutting-edge as any film released in 2017.