Guy Ritchie is that fun friend whose texts you don’t always return because his energy level is always cranked up to 10, and even when you’re in the mood for him, he still wears you out. His best entertainments are 1990s lad mag confections, chock full of funny, well-dressed, hardboiled men (and a couple of women) who bust each other’s chops when they aren’t joining forces to steal something. They’re the kinds of films you forget exist until you stumble across them and end up watching the whole thing again because the tone is just right—edgy but lighthearted—and never for a moment does the movie pretend that watching it is going to make you a better person. “Lock, Stock and Two Smoking Barrels,” his two Sherlock Holmes films, “Snatch,” the bizarre self-help action film “Revolver” and 2015’s unexpectedly marvelous “The Man from U.N.C.L.E.” are assortments of savory treats presented in the most stylish boxes Ritchie can devise.

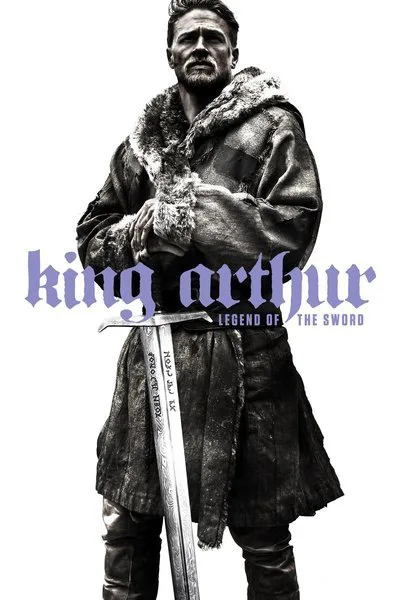

But there are times when Ritchie makes his own style the star of the film, crowding out the actors and the story because neither is terribly interesting. The result is an oxymoron: a frenetic slog. That’s unfortunately what happens to “King Arthur: Legend of the Sword,” a knowingly anachronistic riff on the legend starring Charlie Hunnam. This version envisions Arthur as a working-class hero with entirely contemporary sensibilities. He was raised in a brothel after his father and mother were murdered by his uncle Vortigern (Jude Law). Vortigern is an unworthy King of England and a pampered sadist who owes a supernatural debt to the Lady of the Lake, envisioned here as a mass of CGI tentacles enfolding three women, one plump and the others slender and curvy.

Ritchie and his cowriters, Lionel Wigram and Joby Harold, aren’t interested in historical fidelity because the historical Arthur was a mystery anyway and they’re mainly having fun here. They take Arthur’s childhood trauma seriously (he keeps re-experiencing it in nightmare form, like Bruce Wayne remembering his own parents’ murder by a mugger) but ultimately treat it mainly as the centerpiece for a standard-issue “hero’s journey,” one that owes quite a bit to the “Star Wars,” “The Matrix” and “Lord of the Rings” films. When he pulls the sword from the stone, he, we and the baddies all know that he is truly The One; when he grips it with both hands and then swings, the earth trembles and the camera starts whirling in circles around and around CGI Charlie Hunnam and his adversaries, in the manner of a video game with 3-D graphics.

This Arthur wears what looks like a brown leather bomber jacket, sports a 2016 movie star haircut, calls everybody “mate,” and makes a big show of not wanting to get involved in politics, much less embrace his destiny. That is, until circumstances require him to round up a crew of hyper-competent misfit outsiders and depose the kind heist-movie style, treating every skirmish and siege as if it were another vault that the “Snatch” guys were hoping to empty. The future Knights of the Round Table are just as contemporary. They’re a multicultural crew: this film’s Sir George is nicknamed Kung Fu George, tutors Arthur in martial arts, and is played by Hong Kong-born actor Tom Wu; Sir Bedivere is a Moor played by Beninese movie star Djimon Hounsou. And the Anglo actors’ characters get a dusting of Dickensian chimney soot to enhance their rough-and-ready bona fides. The future Sir William (Aiden Gillen), master of the longbow, goes by Goosefat Bill Wilson.

I love all this stuff in theory—it’s not far from what Martin Scorsese did in “The Last Temptation of Christ,” populating ancient Jerusalem with New Yorkers, Midwesterners and Brits who spoke in their native accents and used modern slang, slicing and dicing the action into music video beats, and scoring the whole thing with Peter Gabriel’s chants and synth beats. The Ritchie sense of style suits a revisionist approach. He’s as slick and easygoing as a rock and roller showman can be, and because the totality of the film is so knowingly absurd—in addition to the slow-motion, acrobatic swordfights, there are gigantic CGI snakes, rats, wolves, and Godzilla-sized Indian elephants—the whole thing feels like a lark even when the characters are being beaten, tortured and executed. There are even moments when Hunnam, not an actor exactly known for his scalawag charm, evokes Errol Flynn’s devil-may-care jerk incarnation of Robin Hood. Astrid Bergès-Frisbey’s version of Guinevere, a witch whose eyes go black when she summons dark forces, is a fresh variation on the character, though it would’ve been nice if Ritchie had allowed her to crack a few jokes like the boys.

No, the real problem is that the movie is unmodulated from start to finish. It never lets up in the exact way that a cocaine addict who wants to tell you his life story before closing time never lets up. Michael Bay has often been accused of turning in feature length motion pictures so over-edited that they feel like trailers for themselves, but I don’t think Bay has ever made a movie as frantically, pointlessly, tediously busy as “King Arthur: Legend of the Sword.” Not content to do that time-tested Guy Ritchie story-about-a-story thing in every other scene of the picture—you know, the bit where a character tells an audience, “And then I sez to him,” and the movie cuts to the same character five days earlier saying, “Put down the money, mate!”—the film does it constantly for two hours, dicing dialogue, performances and story points into microscopic narrative particles that disintegrate in the mind.

On one level, you have to admire the skill necessary to tell a story in this manner. You can’t just make a six-hour film and then cut it down to two. You have to think about how every piece, no matter how small or large, will fit with every other piece when the whole narrative is stitched together. But the downside of this strategy is that it doesn’t allow room for any single moment to truly live and breathe, and it’s in such moments that we really get to know a character and care about what happens to them. The emotional heavy lifting that might be done by acting, writing and careful direction is done here in shortcut form by whooshing, tilting, diving camerawork, ominous “whoosh” and “boom” noises on the soundtrack, and other signifiers of awesomeness.

There’s so much narrative and visual motion, such fast cutting, such loud music, and so many rapid shifts of time and place that on those rare occasions when the movie slows down and lets two characters speak to each other, in relative quiet and at length, it feels as if something’s gone wrong with the projection. Ritchie keeps rushing us along for two hours, as if to make absolutely certain that we never have time to absorb any character or moment, much less revel in the glorious, cheeky ridiculousness of the whole thing. The entire movie is an information delivery device with top-dollar production values, forever mistaking getting to the point for the point itself. It’s the legend of King Arthur as told by an auctioneer. I’m not sold.