Some of the best biopics are the ones that focus on a pivotal point in a major figure’s life and use that period as a prism through which to understand what makes that person tick, what makes that person matter. Che Guevara’s road trip in “The Motorcycle Diaries” and Steve Jobs’ product launches in “Steve Jobs” immediately come to mind. They don’t try to give a celebrity the complete cradle-to-grave treatment, but rather provide a more intimate, specific look.

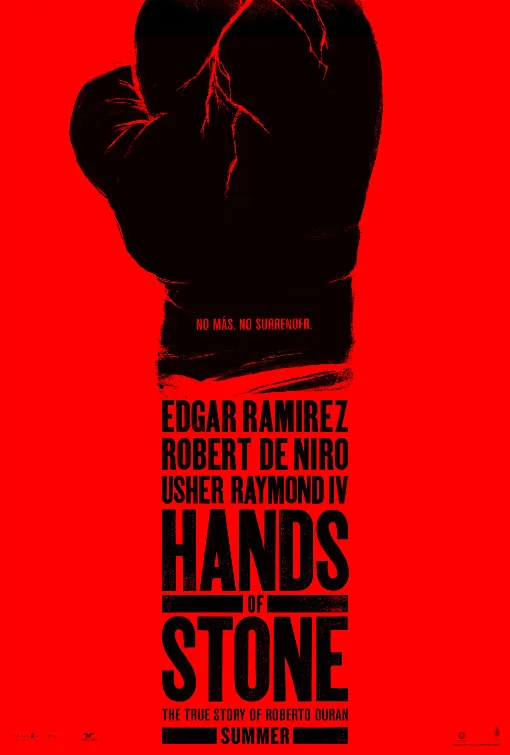

“Hands of Stone,” about the legendary boxer Roberto Durán, could have used such an approach. It’s clearly there in his rivalry with American “Sugar” Ray Leonard. Their back-and-forth in and out of the ring is just tantalizing—the most compelling part of the whole movie. And Edgar Ramírez and Usher Raymond bring these very different fighters vividly to life.

Instead, writer/director Jonathan Jakubowicz depicts Durán from his impoverished youth as a scrappy kid on the streets of Panama through his rise in the sport, his thrilling capturing of the welterweight title against Leonard in 1980, his fall in the famous “No Mas” rematch and his subsequent, triumphant return as light middleweight champion at Madison Square Garden.

That’s a lot of ground to cover. Jakubowicz also skips around in time to cram in Durán’s family life with his wife and five kids, the turmoil that rocked Panama during Durán’s early years, the swelling sense of national pride as the Panama Canal returned to the country’s ownership and the resentment Durán carried as an adult over the American father who abandoned him as a child. He also tells the whole tale from the perspective of Durán’s trainer, Ray Arcel, a legend in his own right with his own backstory and baggage.

Robert De Niro, whose deeply Method-y portrayal of boxer Jake LaMotta in “Raging Bull” gave us one of cinema’s most indelible performances, plays Arcel, which theoretically should be exciting in itself. De Niro dials it down here and does some of the most honest and understated work of his late career. But he’s stuck over-explaining everything in voiceover—about Durán, about Arcel’s decades-old mob troubles, about this historical period, about boxing in general—which only contributes to the sensation that we’re watching yet another paint-by-numbers biopic. In trying to encompass way too much, “Hands of Stone” ends up feeling superficial and unsatisfying.

The performances are really strong, though. That’s what’s so frustrating; you just know there’s a better movie in here waiting to burst free. Ramírez may look distractingly too mature at first to be playing a 20-year-old Durán in 1971, but his swagger is electrifying, from his flirtation with the woman who would become his wife (Ana de Armas) when she was just a teenage schoolgirl to the way he trash-talks Leonard in Montreal leading up to their big showdown. But Ramírez also has the depth to depict Durán’s darker moments: his pent-up anger, hunger and self-indulgent tendencies once he becomes rich and famous. It’s enough to make you wish it were all in the service of a better script. De Armas, meanwhile—who recently appeared in a similarly underwritten supporting role as Miles Teller’s fiancée in “War Dogs”—has a hugely charismatic presence. But except for a couple of showy moments, she gets little to do besides function as the dutiful wife in a sexy array of disco-tastic costumes.

Durán’s more influential relationship is with Arcel, who functions not only as his trainer but also as a father figure, even though he promised the mob (represented in a couple of scenes by the always-welcome John Turturro) that he’d walk away from the sport. That organized-crime element of the story never feels like a real threat; similarly, the introduction of Arcel’s daughter about halfway through the movie comes out of nowhere and never gets developed. The two other men who were major early forces in Durán’s life—a Fagan-like figure who taught him how to survive on the streets and his first trainer—barely get fleshed out, either.

The real missed opportunity, though, was in choosing not to make the Durán-Leonard rivalry the center of “Hands of Stone.” The actors playing them present such an intriguing clash of styles—Ramirez is all bravado and machismo, Raymond is all coy, cool charm. The boxing scenes themselves are shot and edited in a rather standard (if somewhat choppy) manner, but it’s the way the relationship between these two men developed outside the ring that gives “Hands of Stone” any sort of real punch.