“The Motorcycle Diaries” tells the story of an 8,000 mile trip by motorcycle, raft, truck and foot, from Argentina to Peru, undertaken in 1952 by Ernesto Guevara de la Serna and his friend Alberto Granado. If Ernesto had not later become “Che” Guevara and inspired countless T-shirts, there would be no reason to tell this story, which is interesting in the manner of a travelogue but simplistic as a study of Che’s political conversion. It belongs to the dead-end literary genre in which youthful adventures are described, and then “…that young man grew up to be (Benjamin Franklin, Einstein, Rod Stewart, etc).”

Che Guevara makes a convenient folk hero for those who have not looked very closely into his actual philosophy, which was repressive and authoritarian. Like his friend Fidel Castro, he was a right-winger disguised as a communist. He said he loved the people but he did not love their freedom of speech, their freedom to dissent, or their civil liberties. Cuba has turned out more or less as he would have wanted it to.

But all of that is far in the future as Ernesto and Alberto mount their battered old 1939 motorcycle and roar off for a trip around a continent they’ll be seeing for the first time. Guevara is a medical student with one year still to go, and Alberto is a biochemist. Neither has ever been out of Argentina. From the alarming number of times their motorcycle turns over, skids out from under them, careens into a ditch or (in one case) broadsides a cow, it would appear neither has ever been on a motorcycle, either.

First stop, the farm of Ernesto’s girlfriend, whose rich father disapproves of him. Chichina (Mia Maestro) herself loves him, up to a point: “Do you expect me to wait for you? Don’t take forever.” Shy around girls and not much of a dancer, Ernesto is unable to say whether he does or not.

The film, directed by Walter Salles (“Central Station“), follows them past transcendent scenery; we see forests, plains, high chaparral, deserts, lakes, rivers, mountains, spectacular vistas. And along the way the two travelers depend on the kindness of strangers; they’re basically broke, and while Ernesto believes in being honest with people, Alberto gets better results by conning them.

They do meet some good new friends: A doctor in Lima, for example, who gets them an invitation to stay at a leper colony. The staff at the colony, and the lepers. A farmer and his wife, who they meet on the road, and who were forced off their land by evil capitalists. Day laborers and their sadistic foreman. A garage owner’s lonely wife. To get to the leper colony, they take a steamer down a vast lake. Guevara stands in the stern and looks down at a shabby smaller boat that the steamer is towing: This is the boat carrying the poor people, who have no decks, deck-chairs, dining rooms, orchestras and staterooms, but must hang their hammocks where they can.

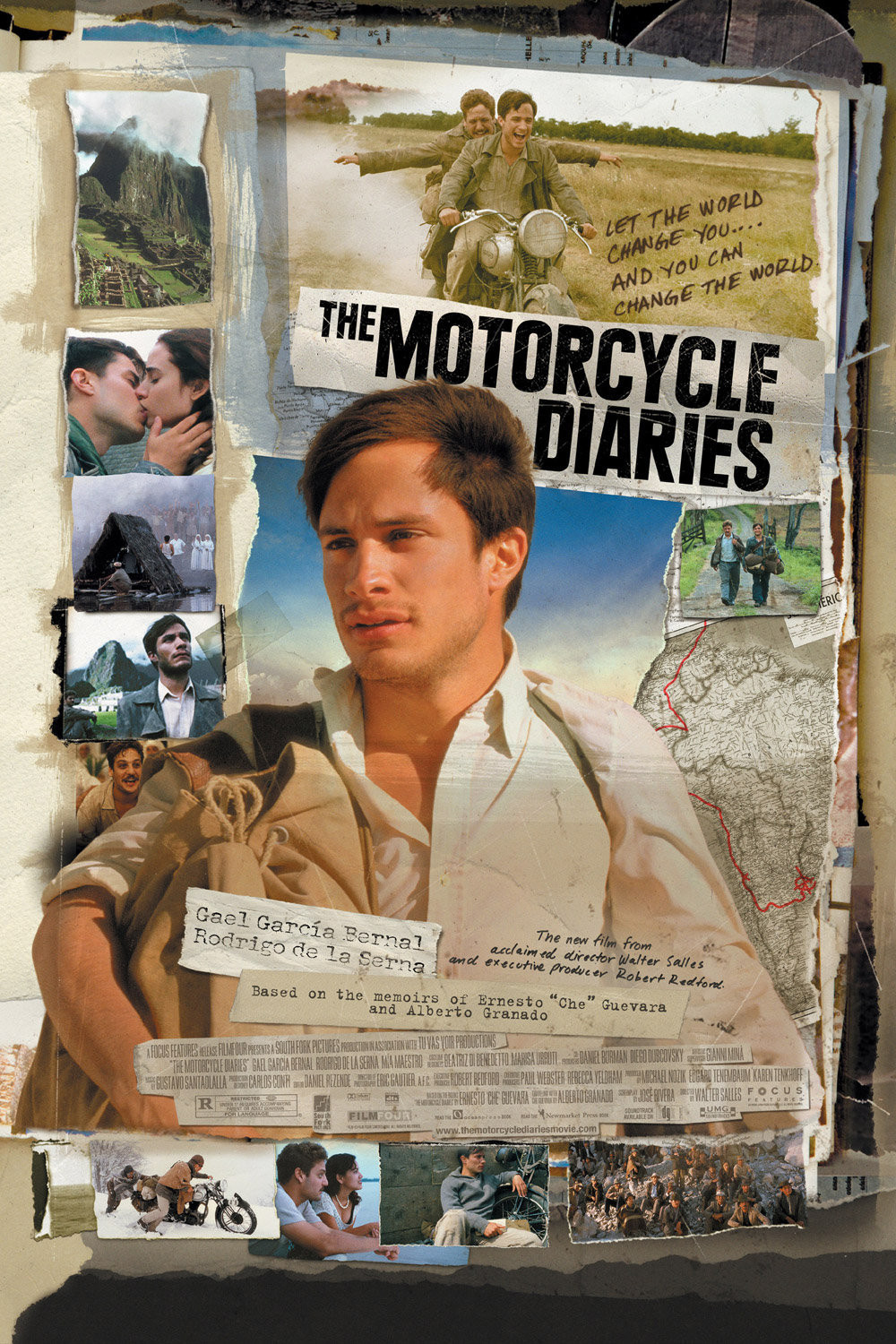

By the end of the journey, Ernesto has undergone a conversion. “I think of things in different ways,” he tells his friend. “Something has changed in me.” The final titles say he would go on to join Castro in the Cuban Revolution, and then fight for his cause in the Congo and Bolivia, where he died. His legend lives on, celebrated largely, I am afraid, by people on the left who have sentimentalized him without looking too closely at his beliefs and methods. He is an awfully nice man in the movie, especially as played by the sweet and engaging Gael Garcia Bernal (from “Y Tu Mama Tambien“). Pity how he turned out.

The movie is receiving devoutly favorable reviews. They are mostly a matter of Political Correctness, I think; it is uncool to be against Che Guevara. But seen simply as a film, “The Motorcycle Diaries” is attenuated and tedious. We understand that Ernesto and Alberto are friends, but that’s about all we find out about them; they develop none of the complexities of other on-the-road couples, like Thelma and Louise, Bonnie and Clyde or Huck and Jim. There isn’t much chemistry. For two radical intellectuals with exciting futures ahead of them, they have limited conversational ability, and everything they say is generated by the plot, the conventions of the situation, or standard pieties and impieties. Nothing is startling or poetic.

Part of the problem may be that the movie takes place before Ernesto became Che, and Alberto (played by Rodrigo de la Serna) became a doctor who opened a medical school and clinic in Cuba (where he still lives). They are still two young students, middle-class, even naive, and although their journey changes them, it ends before the changes take hold. (Note: To be fair, I must report that a Spanish-speaking friend tells me the spoken dialogue is much richer than the English subtitles indicate.)

Salles uses an interesting device to suggest how their experiences might have been burned into their consciousness so that lessons could be learned. He has poor workers, farmers, miners, peasants, beggars, who pose for the camera, not in still photos, but standing as still as they can, and he uses black and white for these tableaux, so that we understand they represent memory. It’s an effective technique, and we are meant to draw the conclusion that the adult Che would help these people, although it is a good possibility he did more harm to them.

As a child I faithfully read all of the titles in a book series named Childhoods of Famous Americans. George Washington chopped down a cherry tree, Benjamin Franklin got a job at a print shop, Luther Burbank looked at a peanut and got thoughtful. The books always ended without really dealing with the adults those children became. But, yes, in retrospect, we can see how crucial the cherry tree, print shop, peanut and Che’s motorcycle were, because Those Young Men Grew Up, etc. It’s a convenient formula, because it saves you the trouble of dealing with who they became.