Here is a Civil War movie that Trent Lott might enjoy. Less enlightened than “Gone With the Wind,” obsessed with military strategy, impartial between South and North, religiously devout, it waits 70 minutes before introducing the first of its two speaking roles for African Americans; “Stonewall” Jackson assures his black cook that the South will free him, and the cook looks cautiously optimistic. If World War II were handled this way, there’d be hell to pay.

The movie is essentially about brave men on both sides who fought and died so that … well, so that they could fight and die. They are led by generals of blinding brilliance and nobility, although one Northern general makes a stupid error and the movie shows hundreds of his men being slaughtered at great length as the result of it.

The Northerners, one Southerner explains, are mostly Republican profiteers who can go home to their businesses and families if they’re voted out of office after the conflict, while the Southerners are fighting for their homes. Slavery is not the issue, in this view, because it would have withered away anyway, although a liberal professor from Maine (Jeff Daniels) makes a speech explaining it is wrong. So we get that cleared up right there, or for sure at Strom Thurmond’s birthday party.

The conflict is handled with solemnity worthy of a memorial service. The music, when it is not funereal, sounds like the band playing during the commencement exercises at a sad university. Countless extras line up, march forward and shoot at each other. They die like flies. That part is accurate, although the stench, the blood and the cries of pain are tastefully held to the PG-13 standard. What we know about the war from the photographs of Mathew Brady, the poems of Walt Whitman and the documentaries of Ken Burns is not duplicated here.

Oh, it is a competently made film. Civil War buffs may love it. Every group of fighting men is identified by subtitles, to such a degree that I wondered, fleetingly, if they were being played by Civil War Re-enactment hobbyists who would want to nudge their friends when their group appeared on the screen. Much is made of the film’s total and obsessive historical accuracy; the costumes, flags, battle plans and ordnance are all doubtless flawless, although there could have been no Sgt. “Buster” Kilrain in the 20th Maine, for the unavoidable reason that “Buster” was never used as a name until Buster Keaton used it.

The actors do what they can, although you can sense them winding up to deliver pithy quotations. Robert Duvall, playing Gen. Robert E. Lee, learns of Jackson’s battlefield amputation and reflects sadly, “He has lost his left arm, and I have lost my right.” His eyes almost twinkle as he envisions that one ending up in Bartlett’s. Stephen Lang, playing Jackson, has a deathbed scene so wordy, as he issues commands to imaginary subordinates and then prepares himself to cross over the river, that he seems to be stalling. Except for Lee, a nonbeliever, both sides trust in God, just like at the Super Bowl.

Donzaleigh Abernathy plays the other African-American speaking role, that of a maid named Martha who attempts to jump the gun on Reconstruction by staying behind when her white employers evacuate and telling the arriving Union troops it is her own house. Later, when they commandeer it as a hospital, she looks a little resentful. This episode, like many others, is kept so resolutely at the cameo level that we realize material of such scope and breadth can be shoehorned into 3-1/2 hours only by sacrificing depth.

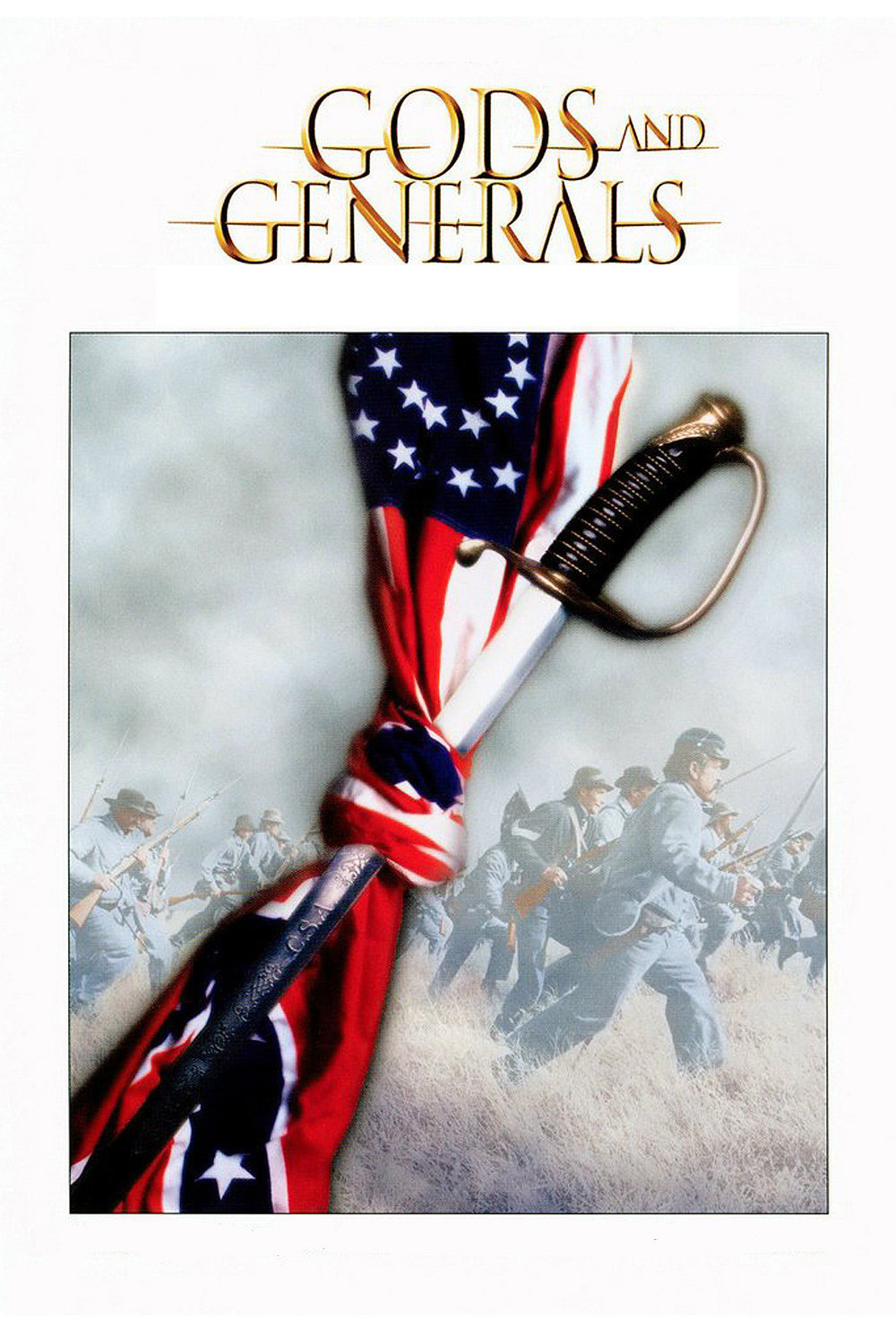

“Gods and Generals” is the kind of movie beloved by people who never go to the movies, because they are primarily interested in something else–the Civil War, for example–and think historical accuracy is a virtue instead of an attribute. The film plays like a special issue of American Heritage. Ted Turner is one of its prime movers and gives himself an instantly recognizable cameo appearance. Since sneak previews must already have informed him that his sudden appearance draws a laugh, apparently he can live with that.

Note: The same director, Ron Maxwell, made the much superior “Gettysburg” (1993), and at the end informs us that the third title in the trilogy will be “The Last Full Measure.” Another line from the same source may serve as a warning: “The world will little note, nor long remember, what we say here.”