Perhaps the two biggest problems with “Fur: An Imaginary Portrait of Diane Arbus” are the last two words of the title. This through-the-looking-glass “Beauty and the Beast” fable has little to do with Diane Arbus, the famous photographer, or with her work, which is not seen in the film. As a Lewis Carroll title card explains, this “is not a historical biography” but instead “reaches beyond reality to express what might have been Arbus’ inner experience on her extraordinary path” to becoming an artist. Sure. All that’s missing is a sense of who Arbus was, and how the fictional journey depicted in the film is reflected in (or, rather, distilled from) her art.

What we’re left with is a gorgeously mounted, impeccably framed fantasy that exhibits the sensuous aesthetic of an ad in Vanity Fair but provides no particular insight into Arbus’ psychological or artistic sensibility.

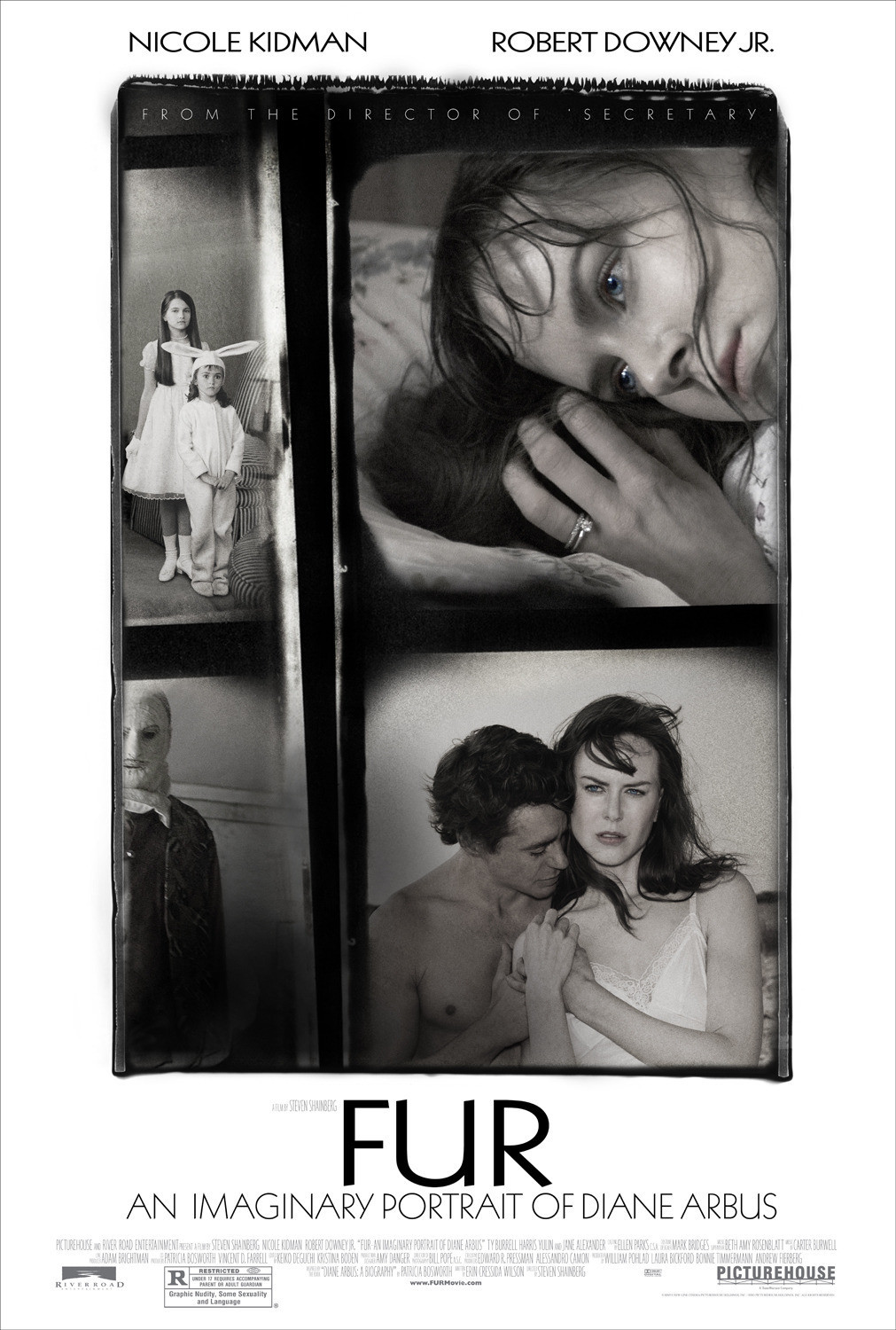

Diane (Nicole Kidman) lives with her husband, Allan (Ty Burrell), a commercial photographer, and two daughters in a Dakota-esque Manhattan apartment/studio, circa 1958. The problem is, she doesn’t feel “normal.” She has secrets, odd desires that frighten and shame her, but thrill her with pleasure precisely because they’re forbidden.

In the opening scene, Diane (pronounced dee-ANN in the movie) and Allan host a fur fashion show for her father’s fancy department store, Russek’s on Fifth Avenue. While wealthy patrons ogle exotic leopard and chinchilla skins, Diane fixates on the gargoyles in the audience, swilling their cocktails and masticating cheesy hors d’oeuvres. Does she find beauty in their grotesquery, as “Fur” claims she does in the deformities and fetishes of those who are marginalized because of their physical or psychological “abnormalities”? Or is hers a satirical vision? Is she attracted to them or repulsed by them, or both?

We’ll never know — at least not from this movie, which is too timid to face these questions that Arbus’ art arouses in the spectator.

On the very same night, a mysterious masked man moves in upstairs. He is Lionel (Robert Downey Jr.), a former circus sideshow freak (by profession) afflicted with hypertrichosis, a form of extreme hairiness. His state excites her. (She also digs kissing the undersides of Allan’s hirsute wrists, but gets turned off when he giggles squeamishly.) Lionel, as it turns out, is a dead ringer for the famous Polish Barnum & Bailey performer Lionel the Lion-Faced Man — as well as Barnum’s even more famous Russian, Jo-Jo the Dog-Faced Boy, and the Beast in Jean Cocteau’s “Beauty and the Beast.”

There’s some convincing static electricity between Kidman and the ambiguously sexual Downey, but it fizzles in the end because the movie plays out its parable so literally: Diane must fall in love with a circus freak to become “Diane Arbus,” the photographer renowned for portraits that emphasize the freakishness in her subjects (and her viewers).

But while the narrative is slogging to hit one allegorical mark after the next, director Steven Shainberg (“Secretary“) does give us plenty to watch. “Fur” is fetishistically sensitive and alert to surfaces and textures. Its images bristle with tactile impressions: fur, wallpaper, fabric, hair, skin.

The movie’s underlying visual concept is a provocative and occasionally delightful one: Art resists compartmentalization. Slowly, Lionel’s exotic, erotic world seeps into Diane’s apartment — his hair clogging her sink, his gramophone reverberating through the heating ducts — until a trap door opens and dozens of freaks descend from Lionel’s place directly into the Arbus family studio. Great idea for an image but, again, a mite literal in its execution.

David Cronenberg’s “Naked Lunch,” with its imaginative transpositions from the life and art of William S. Burroughs into a fictional narrative, would be the ideal model for a project like “Fur.” But Cronenberg had Burroughs’ cooperation and the rights to several of his books. “Fur” is crippled by its inability to invoke Arbus’ actual work, even while it draws upon characters and incidents from her life (“inspired by” Patricia Bosworth’s Arbus biography). The more liberating creative approach may have been to let go of Arbus’ name and the “imaginary biopic” angle entirely and make the film about a fully fictional Arbus-like character. That might have given the filmmakers the freedom to go all the way with their conceit, unrestrained by the compulsion to offer a tidy moral and artistic lesson for their fable in order to “explain” Arbus’ decision to leave her family and become a photographer.

As it is, “Fur” is stuck with offering a reductive and unenlightening view of the real Arbus.