William S. Burroughs is one of the most pathetic figures in modern literature, his sadness made more poignant because it has been drawn out for so long. His cadaverous presence gave a hollow echo to a key scene in “Drugstore Cowboy,” in which he was a junkie ex-priest who has long decades of pain in his eyes. It didn’t seem like acting. And in a recent documentary about his life, Burroughs came across as a man who walks around with something wounded inside, something that hurts so much that his spirit simply shut down.

That aspect of Burroughs is celebrated at feature length in “Naked Lunch,” the new David Cronenberg film in which Peter Weller gives a performance as evocative as it is depressing, as a fictional character obviously meant to be taken as the author. The film opens with “William Lee” making one of his periodic attempts to go straight. He has kicked drugs, he claims, and is gainfully employed as an insect exterminator. But his wife (Judy Davis) is addicted to the bug powder, and so is Bill, to such an extent that millions of cockroaches owe him their lives.

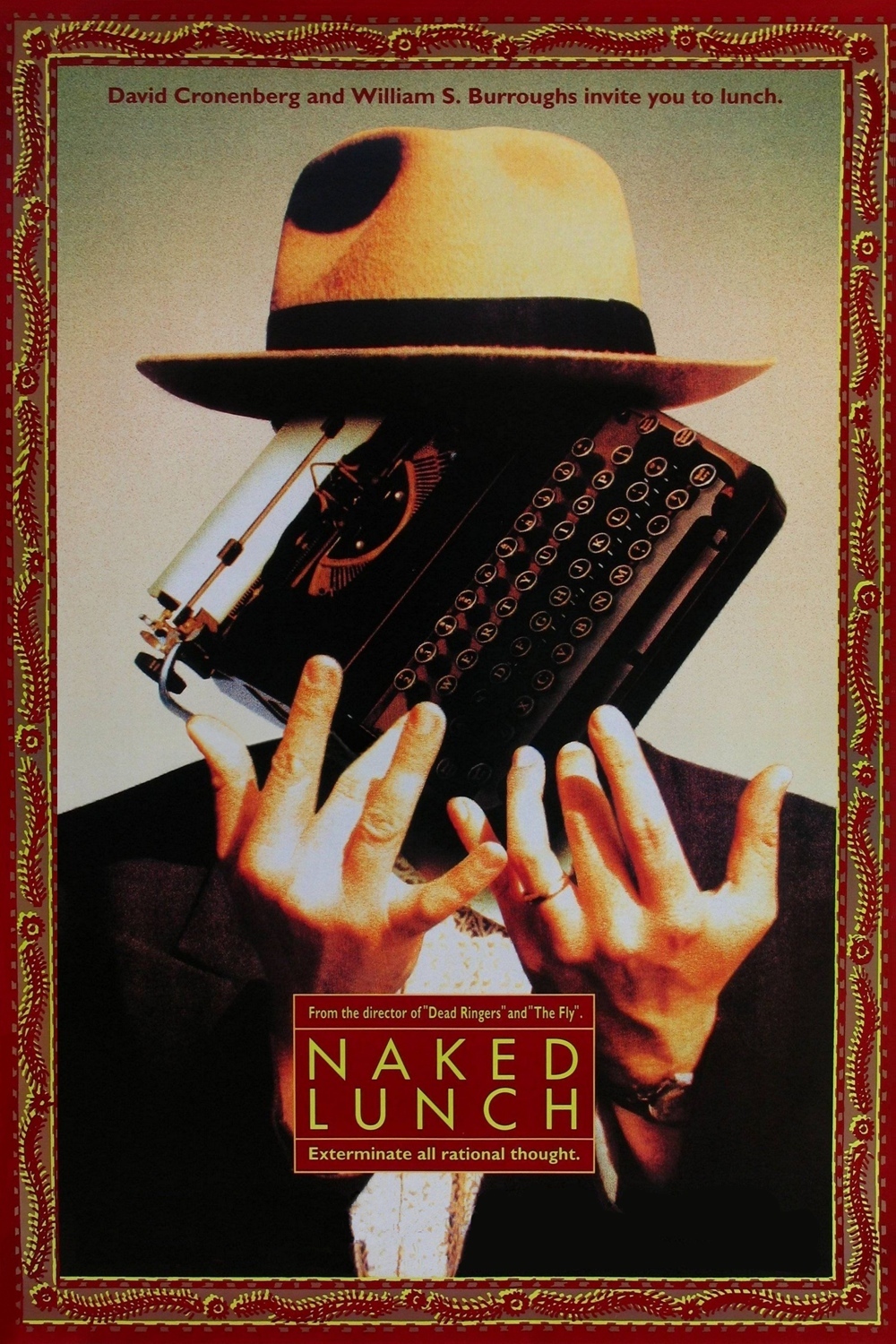

Weller has studied the film on Burroughs and probably even met the man. He has the manner down flat: The low, flat, graveled voice. The dead eyes. The anonymous suits and ties, worn as a disguise for the outlaw inside. The fedora pulled low on the forehead. The lack of any visible display of emotion. I did not like the character – who could? – but I admire Weller’s artistry in creating this portrait of the living dead.

The character is an unsuccessful writer who has turned to pornography to support himself, and of course Burroughs did much of his now-acclaimed work in that genre, including “Naked Lunch.” His days, when they are not spent in desultory work or experiments with bug powder and other substances, are devoted to aimless sessions of cynical talk, delivered in perfunctory monosyllables. During one such evening he and his wife perform their celebrated William Tell party trick, during which he shoots things off her head with a pistol. This night he is a bad shot, and the bullet hits her square in the forehead.

Such a tragedy actually did occur. Burroughs did accidentally shoot his wife, although apparently he did not read her death as a warning that maybe he should cut back on the old bug powder. In the film, her death opens the yawning pits of paranoia and schizophrenia for the author, who begins to hallucinate that his wife is still before him, who thinks he is being investigated by “Interzone,” and whose typewriters turn into large bugs that communicate through their pulsating sphincters.

Joining Weller are a group of supporting actors who are all able to hit the dry note of insects rustling in the walls. Roy Scheider is the quack doctor and drug dealer, and Ian Holm and Julian Sands are inhabitants of Interzone. Davis, as the wife, is playing her second muse of the year (she was the inspiration for the Faulkner character in “Barton Fink”), in a performance so different from the first it underlines her range.

But I’m spinning my wheels here, maybe to avoid the paradox of this film: While I admired it in an abstract way, I felt repelled by the material on a visceral level. There is so much dryness, death and despair here, in a life spinning itself out with no joy.

Burroughs inhabits the madhouse of his mind, and as he is addressed by bugs and phantoms and the specter of his murdered wife, the most horrifying thing of all is that he reacts in the same detached, cold way. All except for a moment of grief he permits himself over her dead body. One suspects he could have cried out with the same rage and hurt all of his life.