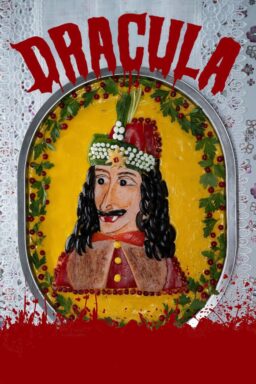

The friendly folks at Hammer Films Ltd., the British specialists in horror flicks, have this thing about tiny glass vials. They’ll use a vial or two in almost every movie they make. Sometimes they have crystal vials, but mostly just your ordinary glass vial.

The vials are handy for storing dehydrated blood from Count Dracula, who left so much blood behind him when he died that, alive, he would have been a godsend to the blood bank, had his blood not been overrun with vampire germs. Has it occurred to anyone, by the way, that the new Illinois blood law distinguishes between blood that is purchased and donated, but makes no mention of blood like Dracula’s, which was … borrowed?

Public prejudice against vampires still runs at a fairly high level, unfortunately, and that is why you never hear of a vampire donating his services when an emergency call goes out for a rare blood type. With a bit of organization and a list of rare blood donors, a competent team of vampires should be able to come back with the necessary plasma in no time. This is not the unsavory prospect it would have been in the 18th or l9th Centuries; the widespread use among vampires of toothpaste has removed one of the age-old barriers to their acceptance.

In any event, “Dracula A.D. 1972” opens with a striking testimonial to the staying power of Dracula’s blood. We remember from “Taste the Blood of Dracula,” an earlier Hammer endeavor, that when his dried blood is mixed with a little water and taken orally in medicinal amounts, the user becomes infected with the count’s evil spirit. That’s more or less what happens again this time.

A young man who looks curiously like Alex (Stanley Kubrick’s hero in “A Clockwork Orange”) wants to be a vampire. He hangs around all day in a strange coffeehouse that looks curiously like the milk bar in “A Clockwork Orange,” and he looks out from under a lowered brow, just like Alex in “A Clockwork Orange” or Dan Walker in his campaign posters. He seems to be a symbol of the general decay at Hammer Films, which, having brought the horror film to a peak of perfection and created the first new horror superstar in years (Christopher Lee), now seems willing to follow the artistic leads of violence-come-latelies like Kubrick. Alas.

Anyway, the novice lays hands on some dehydrated Dracula blood, liquefies it during a bizarre ritual in a bombed-out church, and sets into motion a complex chain of forbidden rituals designed to display Stephanie Beacham’s cleavage to the greatest possible advantage.

This isn’t a terrific rationale for another horror flick but, given Miss Beacham’s ability to heave, and her bosom to heave with, it will have to do. On leaving the theater, I was given an honorary membership card in the Count Dracula society, and a lapel pin which I inadvertently stuck myself with. And not a vial in sight.