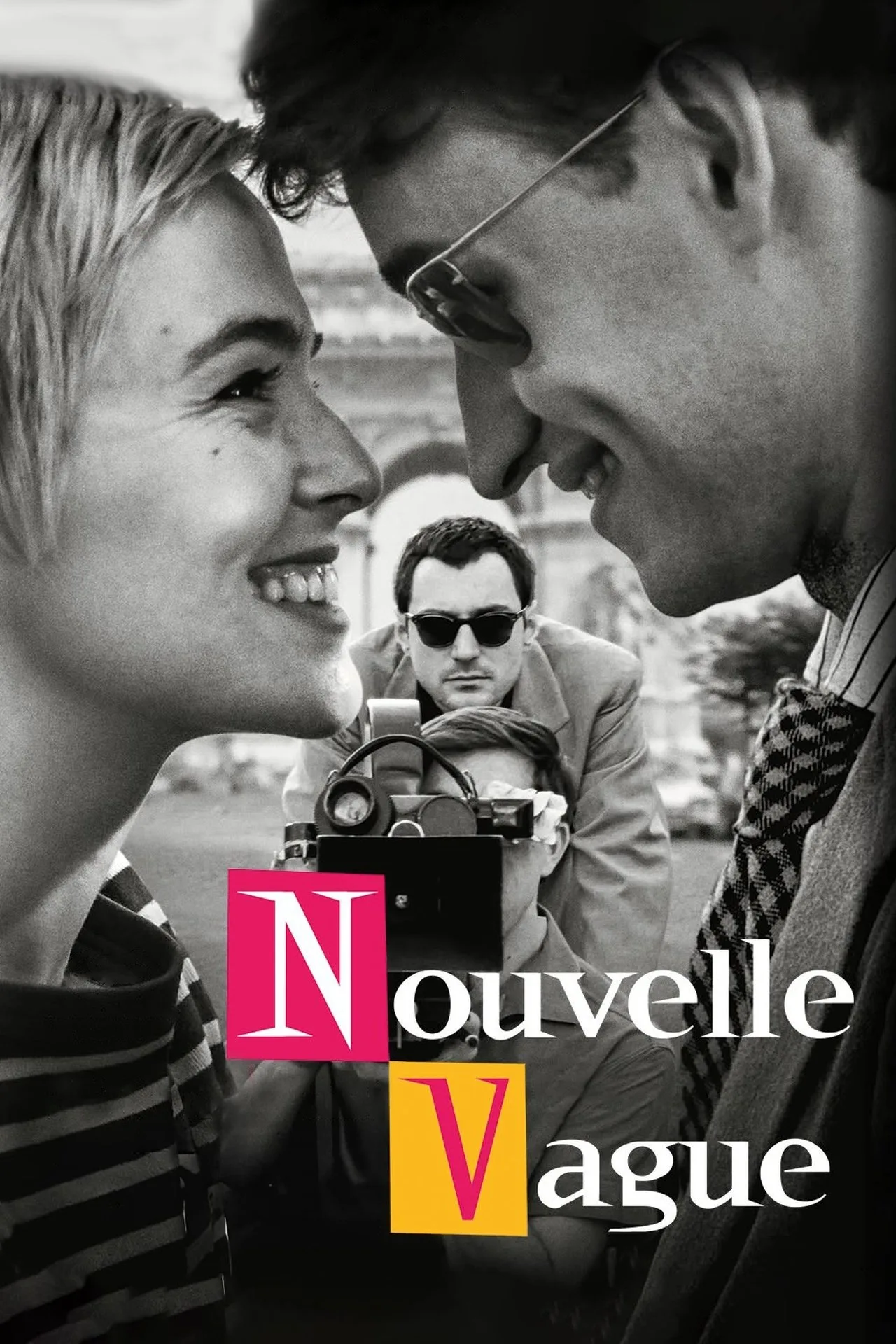

Shot in the fashion of its title’s namesake, Richard Linklater’s “Nouvelle Vague” is a tribute to the French New Wave and a charming retelling of one of cinema’s most storied debuts: Jean-Luc Godard’s “Breathless.” Born out of love for the era and the many players that influenced generations of cinephiles and filmmakers around the world, “Nouvelle Vague” transports viewers to a black-and-white vision of the creative milieu of 1959 Paris at the moment when one bold director is about to make history—only none of his collaborators or colleagues know it yet. It’s the kind of movie that could spark interest in the French New Wave or earn scorn for packaging the art movement that thumbed its nose at the establishment so succinctly.

After many of his fellow writers at “Cahiers du cinéma” made their first movies, film critic Jean-Luc Godard (Guillaume Marbeck) feels the time is right to make his own mark on cinema. He convinces flustered producer Georges de Beauregard (Bruno Dreyfürst) to greenlight a treatment co-written with fellow critic, friend, and filmmaker Francois Truffaut about an aspiring gangster. Godard approaches American movie star Jean Seberg (Zoey Deutch) and convinces her to join in his revolutionary act of cinema along with another early collaborator, Jean-Paul Belmondo (Aubry Dullin).

As production on “Breathless” commences, it’s anything but ordinary. The cast and crew spend precious time lounging in cafes when not hyper-focused on filming each shot just one or two times without a completed script, much of which is written day-of or improvised as the dialogue would be dubbed later. As Beauregard panics and Seberg loses patience with the would-be filmmaker, only Godard knows what he wants his film to look like and fights to keep his vision his own.

In paying tribute to the era’s scrappy low-budget aesthetics, Linklater and cinematographer David Chambille give “Nouvelle Vague” a vintage treatment: 4:3 aspect ratio, film grain, and even keeping the marks on the top right corner of the screen to signal a reel change for the projectionist. Chambille’s camera is much steadier than Godard’s insistence on handheld shots, capturing a larger view of events as the young director develops his style in real time. Linklater seems to delight in showing how Godard got his shots and how few takes he needed.

The film offers a few crafty tips and quotes from Godard and his other contemporary filmmakers, like an Introduction to Film course. “Art is not a pastime, but a priesthood,” says an on-screen Jean Cocteau (Jean-Jacques Le Vessier). Later, Godard gives his famous line, “All you need for a movie is a girl and a gun,” almost as a throwaway, just one of many for cinephiles to recognize or students to learn for the first time. The movie is also riddled with famous names, which Linklater dutifully lists with each character, introducing his audience to directors like François Truffaut (Adrien Rouyard), Claude Chabrol (Antoine Besson), Jacques Rivette (Jonas Marmy), Eric Rohmer (Côme Thieulin), and many others.

Perhaps Vincent Palmo Jr. and Holly Gent’s screenplay for “Nouvelle Vague” is too neat a package, too sleek and easy to take in, given that Godard’s film was essentially a shock to the establishment for his daring choices. Godard’s mantras weren’t so much memes as they were intended to throw convention out the window and redefine the definition of what cinema could be. Yet, this digestible approach has the potential to reignite an audience’s appreciation for the French New Wave, showing the experimentation and sacrifices these scrappy band of outsiders made to create a movie that felt so radically different.

As for Godard himself, newcomer Marbeck portrays the director like a sphinx-like Puckish spirit, almost always hiding behind sunglasses while speaking in quotes and philosophical musings between cigarette puffs, purposefully courting chaos with a defiant smirk. It does feel more like a caricature than a character, but for the purposes of “Nouvelle Vague,” Godard’s obscure nature works opposite Deutch’s exasperated Seberg.

Traumatized by her collaboration with Otto Preminger on “Bonjour Tristesse,” Seberg reluctantly participates in Godard’s film to work with other greats in the French New Wave, but grows tired of not having lines and Godard’s puzzling direction. Their adversarial dynamic keeps the set tense even when the film’s producer isn’t fretting about the cost. However, Dullin’s Belmondo understands that this is all just a game, treating Godard like a sparring partner behind the camera and matching his erratic direction with a macho performance of a wannabe gangster. In due time, Belmondo and Seberg’s chemistry is noticed by more than the camera, and the trio’s dynamic becomes its own thrilling subplot.

In some ways, Linklater’s “Nouvelle Vague” is similar to many other films about filmmaking, including Truffaut’s “Day for Night.” But it also reminds me of Richard Attenborough’s 1992 biopic “Chaplin,” which, while more traditional in tone and approach, breaks down how Charlie Chaplin the filmmaker approached staging his comedic pratfalls, playing against expectations, and developed some of the most memorable moments in film history. It’s not a great movie on the level of, say, “The Gold Rush” or “The Kid,” but watching that movie one morning on cable introduced this young film fan to Charlie Chaplin when I was getting interested in film history. It inspired me to go to the local used DVD store at the nearest outlet mall, where I came home with two discs of Chaplin shorts to begin my education on silent movies.

Linklater has made plenty of great movies on his own, from The Before Trilogy to last year’s “Hit Man.” But with “Nouvelle Vague,” it feels like he’s sharing his love of movies and one of the filmmakers that influenced him, who got him to sit straight in his chair, perhaps lean into the TV to get a better look, to watch his movies over and over again as they held onto interest for decades as he became an accomplished storyteller in his own right. Among film types, there is perhaps no greater love language than sharing the art that speaks to you. Linklater not only pays his respects to Godard but also shares that adoration for his craft with his own audience.

This review was filed from the world premiere at the Toronto International Film Festival on September 8. It opens theatrically on October 31 and on Netflix November 14.