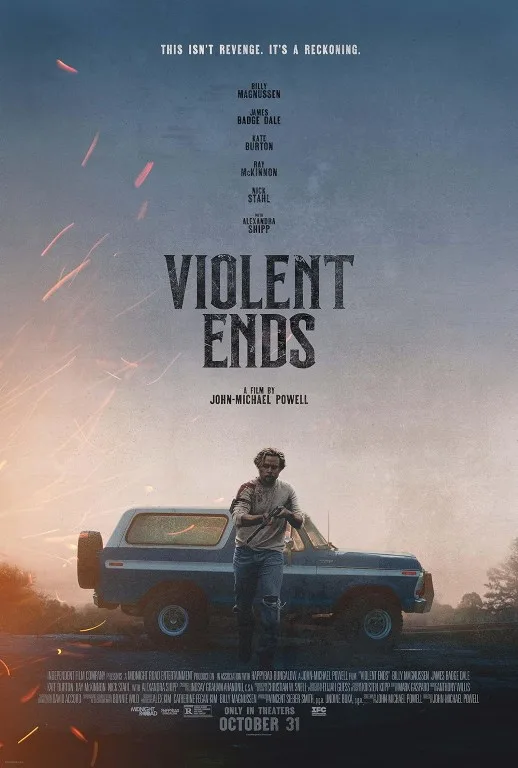

For much of “Violent Ends,” a standard crime revenge thriller from writer/director John-Michael Powell, there is an overwrought sense of angst. Set in the Ozark Mountains, this Southern tale certainly teases the kind of intrafamily rivalry whose drug-dealing dangers should elicit intrigue. But it doesn’t quite know how to square a vengeful Lucas Frost (Billy Magnussen), whose straight-edge life is bent by tragedy, into a full-circle story. While Powell’s film is highly bloody and invested with psychological realism, it lacks a pulse and curiosity that doesn’t befit the excitement promised in the title.

That carelessness begins with the film’s opening quote: Violent beginnings have violent ends. The Romeo and Juliet reference somewhat makes sense for a film whose intrafamilial drug war between three brothers—Ray and Donny Frost control cocaine while Walt handles the meth—threatens Lucas’s happiness with his fiancée Emma (Alexandra Shipp). Its symbolic execution, however, dilutes the verse into a mere passing allusion.

“Violent Ends” doesn’t find further meaning in its want for mystery either. See, Lucas wants nothing to do with the family business, going so far as to visit his father, Ray (Matt Riedy), in prison to tell him as much. Instead, Lucas plans to move far away with Emma to raise a family. That hope is dashed, however, when a botched robbery of a scrapyard by a trio of masked men leads to Emma’s death.

While Ray’s sheriff mother, Darlene (Kate Burton), investigates the identity of the third man, Lucas disavows the justice system’s tepidity. He already knows his cousins Eli (Jared Bankens) and Sid (James Badge Dale), the latter having been recently released from prison, are at least two of the killers. Ignoring the possibility of igniting an all-out familial drug war, Lucas teams with his half-brother Tuck (Nick Stahl) to hunt his cousins and to discover the identity of their accomplice.

In chronicling Lucas’s vengeful pursuit, Powell does imbue him with some groundedness. For one, it’s clear that Lucas and Tuck aren’t cut out for their family’s underworld heritage. They struggle to enact the kind of reign of terror that’ll lead to others turning on Eli and Sid. Instead, every single one of their schemes blows up in their face: from approaching Walt with an offer of control in exchange for information to pinpointing Eli’s whereabouts at a farmhouse. They’re even framed on a drug charge in a negotiation gone wrong. These failures are given greater weight by Magnussen’s taciturn performance, which relies on a stout posture and a frozen face to translate the bitter anger Lucas feels.

The film unfortunately stumbles in balancing Magnussen’s quiet performance. While Dale makes some inspired choices—from his shaved haircut to his menacing sauntering—Powell limits Sid’s screentime and his range. With such a short time in front of the camera, Sid’s sadism becomes a blunt instrument whose impact is barely felt. That leaves Magnussen to shoulder the burden of a film whose cold apathy leaves little room for the audience to feel.

The setting, lighting, and characters are all grim. Even the blood looks like burnt mahogany. As you’d expect, the titular violence also reaches for gruesomeness: heads are blown off, torture occurs, and open psychological wounds lead to savage scenes of payback—employing an immersive lens that engenders more shock than awe. Powell’s insistence on crafting a gloomy, hyper-violent thriller would be commendable and even noteworthy if he committed to that tone. But an emotionally cheap epilogue featuring one of Lucas’s happy memories with Emma spoils that mood, allowing Powell to stand away from the carnage he wrought.