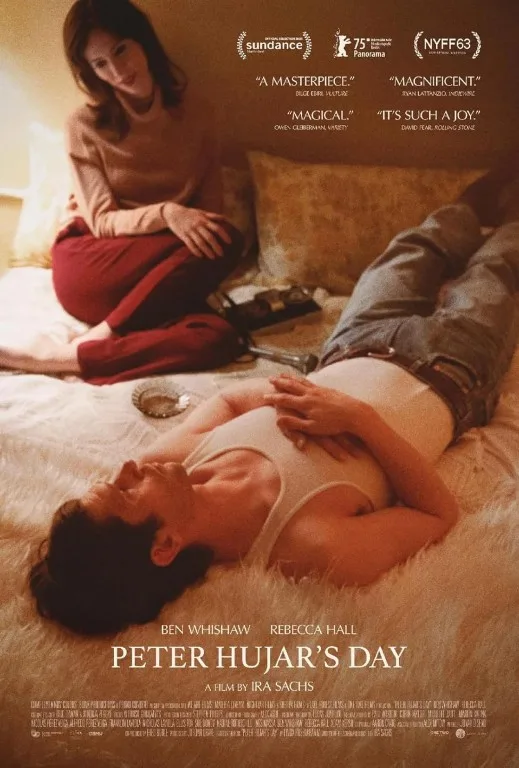

In 1974, Linda Rosenkrantz recorded her friend and photographer Peter Hujar talking about his previous day. She prompted him with questions, and he divulged every detail that came to mind, sometimes even trailing off into personal tangents and backstory. The recording was meant for a book about artists and how they spent their days, which never quite materialized. Decades later, a transcript of their taped conversation is all that remains of that afternoon. That is, until director and writer Ira Sachs artfully recreated their time together in “Peter Hujar’s Day.”

Based on Rosenkrantz’s book, the transcript of the same title, “Peter Hujar’s Day” jumps right into the conversation between Rosenkrantz (played by Rebecca Hall) and Hujar (played by Ben Whishaw). The pair cover the minutiae of Hujar’s previous day–the back-and-forth negotiations over photography gigs, the never-ending list of chores, the casual offers of sex and parties. She asks follow-up questions to get him to talk more, digging up more details about his feelings and the otherwise unremarkable elements that slip from our minds in our daily routines.

Except for a busy photographer like Hujar, those details include remembering to water the plants before heading over to Allen Ginsberg’s place in the East Village, a few blocks away, and making time for laundry while comparing his work to that of an established fashion photographer like Richard Avedon. In addition to making plans for dinner with friends, Hujar must also calm Ginsberg’s objections to being photographed in a portrait style. While he’s recounting stories both exciting and mundane, his friend responds with jokes, curiosity, and care, offering her own input into his life. It’s all in a day’s work for the ambitious artist in 1970s New York City.

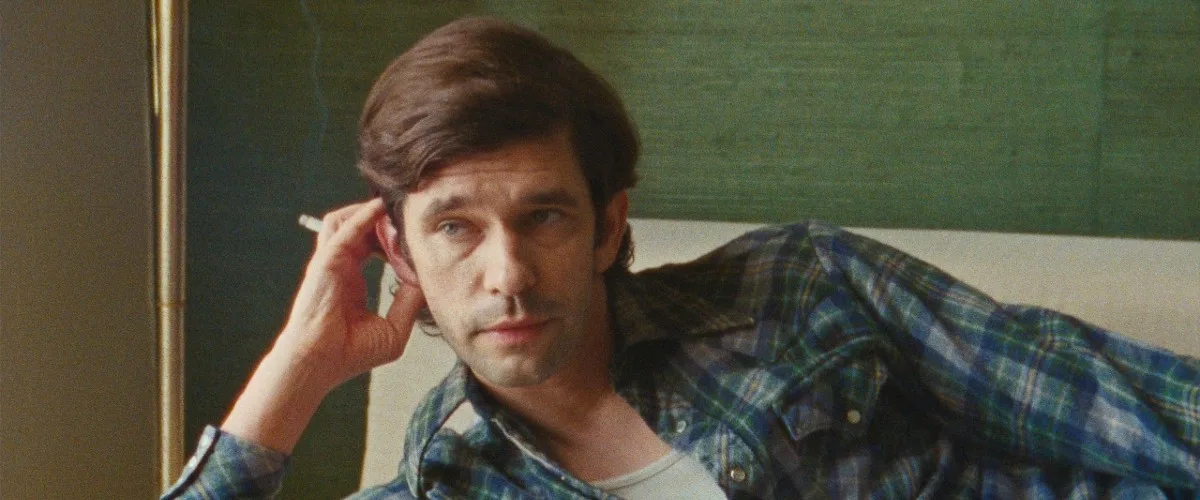

Sachs’ film is a delightful time capsule of the era, complete with Hujar’s steady stream of name-dropping famous friends and neighbors, including Susan Sontag, Fran Lebowitz, William Burroughs, and, of course, Ginsberg. Whishaw is breathtakingly adept at convincing you he’s recalling off-the-cuff memories, interrupting his thoughts and revising stories with new details as he’s going along. While Hall’s Bronx accent is less assured, she’s nonetheless a great foil to keep Whishaw talking, extracting details from his character with a knowing smile, thrilled to get so many personal and factual particulars out of him.

The story is full of little slices of New York City life, of how one got in touch with one another back then, and even the prices of what Hujar paid for certain items, like buying cigarettes for 56 cents, a hot dog for 89 cents, and spending only $7.43 for two meals from a local Chinese restaurant. Sachs, along with cinematographer Alex Ashe, filmed “Peter Hujar’s Day” on 16mm film stock, occasionally letting the film reel run out, in keeping with the free-wheeling nature of the characters’ conversation.

Between the movie’s vintage film grain and Rosenkrantz’s 1970s apartment, Sachs establishes the film’s retro sensibility early on. However, by straying away from conventional biopic fashion, he breaks up the pair’s conversation for occasional portrait sessions, creating a moving tribute to the subject of his film.

Despite the limited setting of Rosenkrantz’s apartment, “Peter Hujar’s Day” is a masterclass in composition, creating movement where there is little and finding an unconventional way to film two people talking. Imagine if “My Dinner With Andre” allowed for the characters to continue talking away from the table. Whishaw and Hall start in Rosenkrantz’s living room, but soon, she gets up to the kitchen. Within a few minutes, Whishaw joins her before moving to the dinner table, eventually sneaking up to the roof for a smoke break, lying on the floor for a change, and later, dancing to a record as the sun sets behind them.

The hours, like Hujar’s stories, are rolling on, and there’s a hint of tiredness and sadness between the two as the warm glow of the day fades. We know that this conversation and the tape recording will come to a stop, just as the many parties and wild stories we once shared will one day also come to an end, as will our time with our friends.

Over a decade after his conversation with Rosenkrantz, Hujar would die less than a year after receiving an AIDS diagnosis. While his work has gained popularity over the years, his photographs are not at the center of the film. Instead, the movie is about the man in his daily life, encompassing both the exciting and forgettable moments. With Sachs’ painterly compositions and Whishaw’s deceptively effortless performance, “Peter Hujar’s Day” is a surprisingly beautiful and subtle tribute to the balancing act it takes to be a working artist.

This review was filed from the premiere at the New York Film Festival on October 8. It opens on November 7.