Taking on a novel that’s already been adapted by two of the greatest filmmakers of all time should give any contemporary director pause, you would think. But Benoît Jacquot shows no signs of intimidation in his “Diary of a Chambermaid,” which he and his co-scenarist, Hélène Zimmer, adapted from Octave Mirbeau’s anti-bourgeois novel of 1900.

The book was adapted to the cinema in 1946 America, by the great French director Jean Renoir. (The first film version was made in Russia in 1916.) Necessarily inhibited by Hollywood censorship of the time, Renoir rendered a sort of antic burlesque of the source material, a highly ironic tale of a chambermaid with social-climbing aspirations who duels with her shifting concepts of integrity as she makes her plays. Paulette Goddard essayed an unusually sassy Celestine. In 1964, with Jeanne Moreau in the lead role, Luis Buñuel made a sardonic and surreal vision. For this film, Jacquot, always a remarkably assured filmmaker (his other pictures include wonderful ‘90s movies such as “A Single Girl,” “Seventh Heaven,” and, more recently, “Farewell My Queen”) expands the source material’s contempt for middle-class hypocrisy into a more expansive misanthropy. But because he (and, of course, his cast) makes his people so engaging, the cynicism feels strangely embracing.

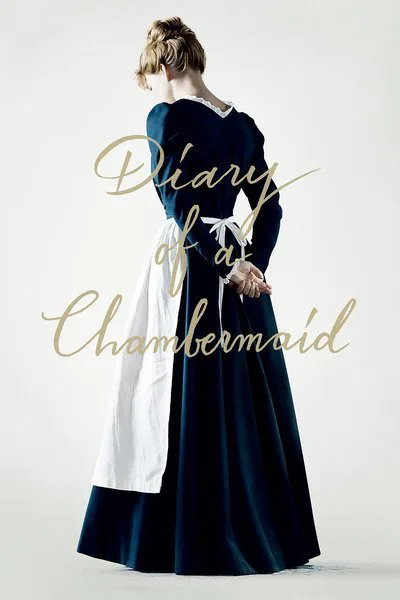

Léa Seydoux (“Blue Is the Warmest Color,” “Spectre,” and also Jacquot’s “Farewell”) plays Célestine here, and when we first see her, in conference with a Parisian overseer who’s trying to place her in a good position, the character is sullen, puffy-eyed. The sometimes abrupt flashback sequences, detailing incidents from other job situations, give us a clear picture of why she’s fatigued, indeed more than fatigued. Dispatched to the French countryside, she’s immediately turned off by her new mistress, Madame Lanlaire (Clotilde Mollet). Madame starts going on about all the precious things she’s got on her mantle and stops in the hallway to ramble on about a clock, one that, if it needs repair, has to be sent to London. “Do you send your cracked chamber pot to London, too?” Célestine asks, barely under her breath. Monsieur Lanlaire (Hervé Pierre), a memorably bonkers shoe fetishist in the Buñuel movie, is here just an ineffectual would-be letch. Monsieur Joseph, the master of the stable, on the other hand, is a burnt-umber vision of masculinity, played by contemporary French cinema’s default masculine archetype, Vincent Lindon. Monsieur Joseph also turns out to be an avid anti-Semite, one whose repellent views are all the more appalling for being pronounced in quiet, even tones.

That Célestine isn’t much bothered by this is a potent, disquieting reminder that a taste for “bad boys” isn’t always an endearing quality. It’s hard to know, though, just what Célestine’s motivations are. She directly conveys more of her own point of view about 30 minutes into the film, when she is heard in voiceover, going over how she might poison her employers, and ultimately rejecting the idea. In the meantime, in a series of handsomely mounted and beautifully judged scenes, the viewer is shown the rough absurdities of Célestine’s present, as in a scene where she visits an eccentric neighbor and learns in a most unpleasant way that he’s not someone to be teased about what he will or will not eat. Her past, too, is unsettling. She is charged with looking after a young man with tuberculosis, and naturally he falls in love with her, with predictably disastrous but not in themselves predictable results.

It’s during this sequence that Célestine has a line of dialogue that is the key to the whole film. Criticizing her charge Georges (Vincent Lacoste, who here looks a bit like a young Keith Gordon) for overexerting himself, she says “You enjoy making yourself ill.” In this movie, that’s the nutshell definition of the human condition. The anti-bourgeois indignation of Mirbeau’s vision is expanded in this film, which can be read as expressing a nearly entirely dismissive skepticism of progressive notions of “empowerment.” This will likely make it unpopular in certain circles. But the immediate effect Jacquot achieves, with quiet droll and some considerable dread, is bracing.