First loves are always the same and always different. The audacity of director Abdellatif Kechiche’s “Blue Is The Warmest Color” lies not so much in the fact that it tells the story of a same-sex first love than in that it tells this story in what some would consider epic detail. The cockeyed open-heartedness of Kechiche’s conception yields a girl-meets-girl-and-so-on story of three hours. They aren’t hours that fly by, either, nor are they meant to; Kechiche, who as it happens is here adapting a graphic novel by Julie Maroh, intends for his viewers to luxuriate and/or empathize in and on particular details. While there have been plenty of movie romances not unlike this, there’s never been one told in such an ambitiously immersive way.

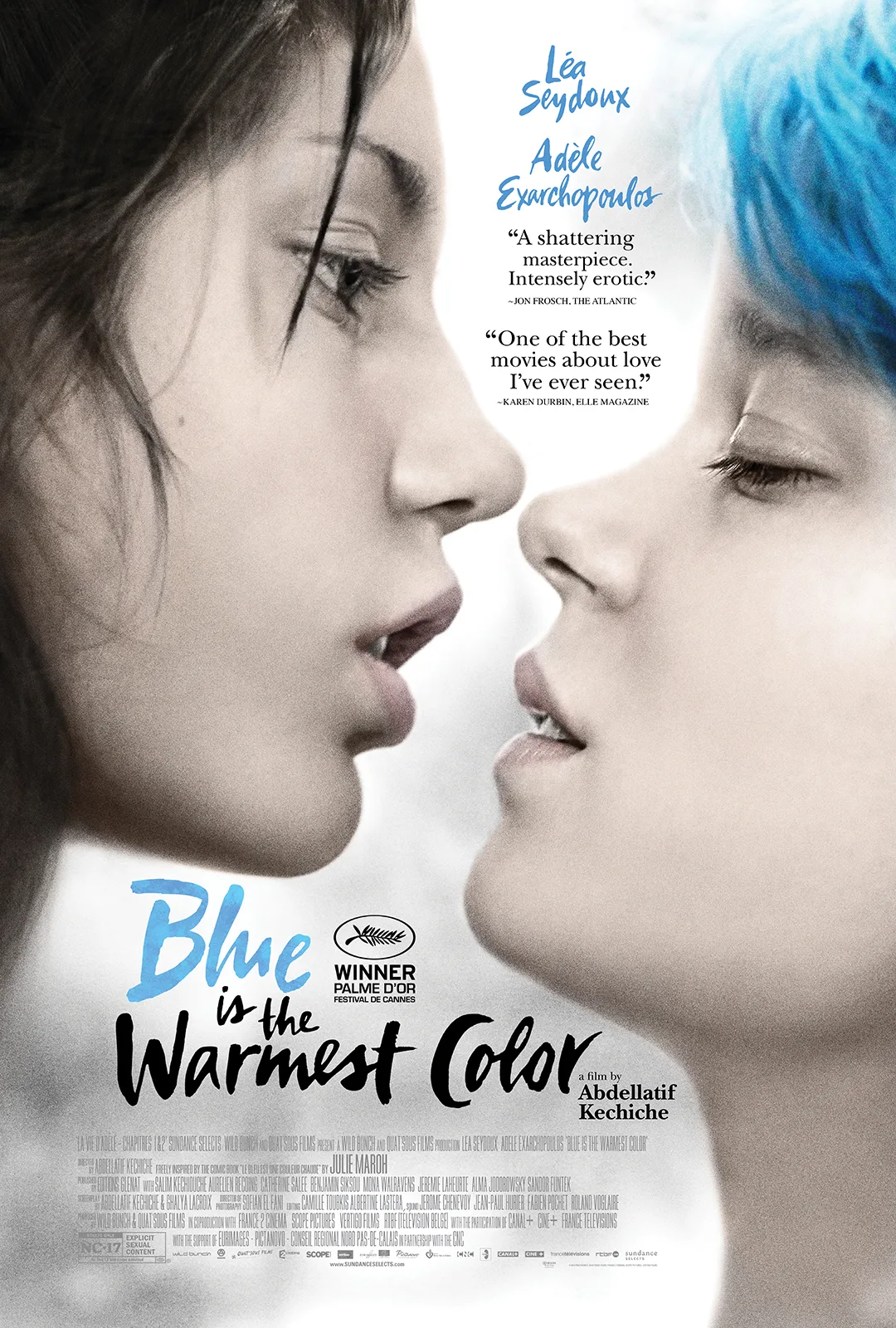

First Kechiche throws the viewer into the world of Adèle (Adèle Exarchopolous), a wide-eyed high-school beauty who should, by the standards of her classmates, be wowing the boys, but instead almost breaks the heart of the one fellow she experimentally dates. Feeling no spark with him, or any other guys, she fixates on a blue-haired older girl she sees on the streets of her provincial French town. And once Adèle really finds Emma (Léa Seydoux), in a lesbian bar, it’s not long before the student and the soon-to-be artiste begin having intense, soul-searching conversations on a soon-to-be-iconic (for Adele) park bench.

Soon after that they’re discovering each other’s keys to sensual ecstasy, in the movie’s already much-talked-about sex scenes. Kechiche has a sense of rapture that extends to all the human senses; Adèle and Emma, in the first throes of romance, eat as much, and as ravenously, as they make love, and there’s particular attention given to Emma teaching Adèle how to appreciate oysters. (There are echoes here, oddly enough, of Claude Chabrol’s little-seen 1990 adaptation of Henry Miller’s “Quiet Days In Clichy,” starring Andrew McCarthy.)

The movie’s transportive quality lies almost entirely with its lead actresses. They are committed to their roles to a degree that could be called exuberant. Neither gives off the slightest hint of working to achieve or inhabit an emotional effect. As the two lovers go, inevitably, out of the state of white-hot attraction and voraciousness and into a domesticity that presents the typical, and typically ugly, problems that an acolyte/ingénue arrangement presents, Adèle seems to grow up before the viewer’s eyes in a way that makes Emma’s self-possessed confidence look kind of complacent.

As it happens, that’s not the thing that starts to drive the lovers apart. I am loath to give away the plot details that some say constitute spoilers, but on the other hand, as I said up front, this is a story of first love, and all stories of first love wind up somehow as stories of first love betrayed. And once the hurting starts, the performances grow more wondrous and sad. So much so that one isn’t much bothered by the material that Kechiche elides in his long film.

Oddly, after going to great pains to establish the homophobia of Adèle’s high-school could-become-mean-girl chums, Kechiche doesn’t depict the way it might have deposited any fallout in Adèle’s life as she moves from school to apprenticeship teaching; nor, after showing a “we’re just study friends” dinner at which Adèle introduces Emma to her parents, do we see any of Adele’s family life after she moves in with Emma. In the aftermath of viewing, this strikes one as odd.

Then there’s the ostensible “male gaze” issue. Yes, Kechiche is a male depicting lesbian love; and yes, he’s a heterosexual male depicting lesbian love enacted between two very attractive actresses. He frequently frames Exarchopoulos in particular so as to accentuate the post-adolescent ripeness of her beauty. (There’s a scene in the movie where Emma and Adèle admire the perfect female posteriors in marble at a museum that suggests Kechiche’s potential apologia: that everyone should be able to appreciate a beautiful derriere.)

As a heterosexual male myself I am of, well, several minds about this. Having a healthy “love” for the female form, one may sensibly argue, is not the same thing as leering at it. And it isn’t as if Kechiche is Max Hardcore, for heaven’s sake. But suggestions that he got a little carried away here are not totally nuts.

In any event, this sort of thing is exactly what sets off the most stimulating kinds of post-moviegoing discussions. If “Blue is the Warmest Color” is not a masterpiece, and I don’t think it is, it’s certainly a provocation, but not a puerile one. Its multi-chambered heart is certainly in one or two of the right places, let’s say.