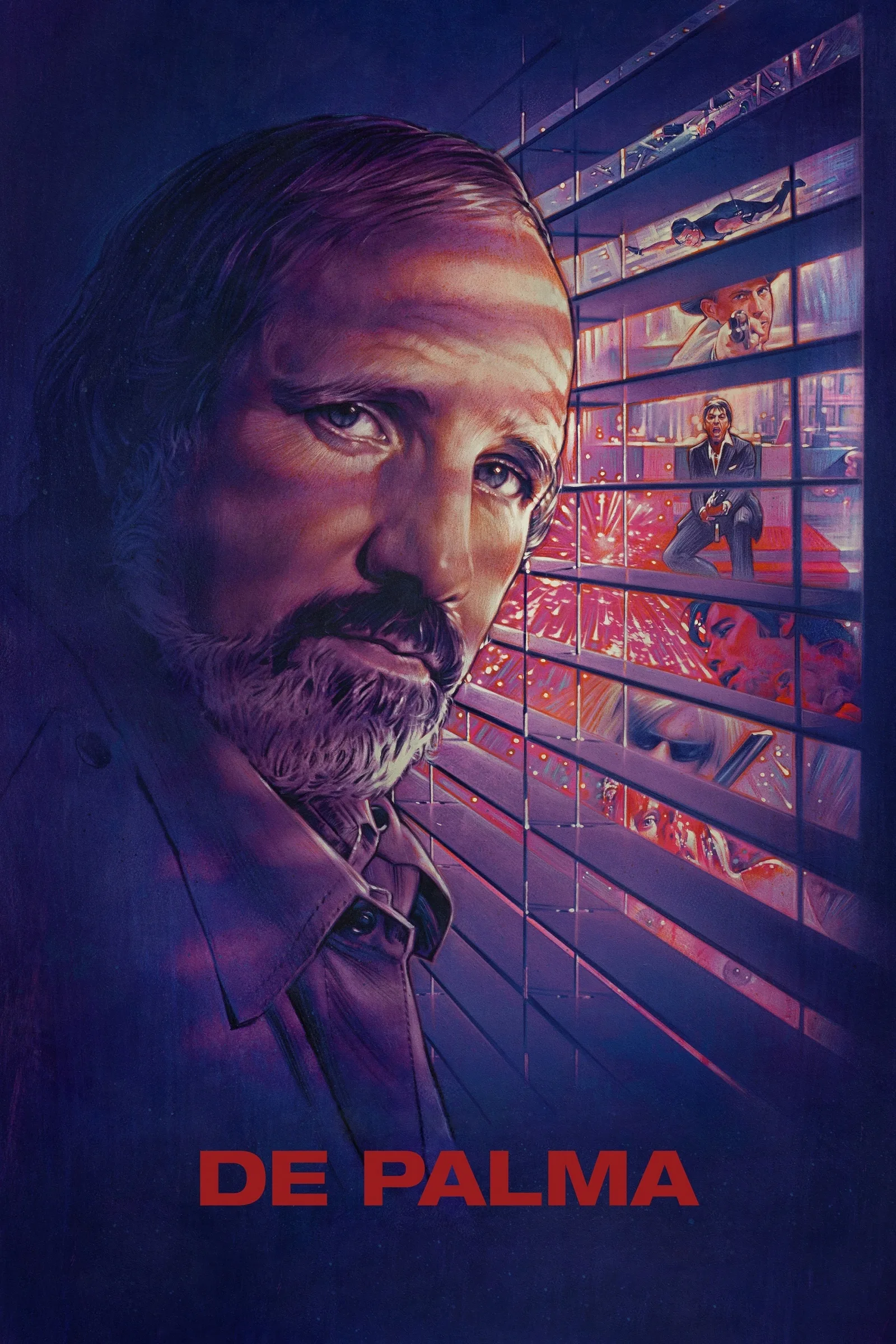

More than just a big-screen fetish object for Brian De Palma’s still-loyal cult, “De Palma” is one of the essential documentaries on Hollywood. This feature-length interview with the controversial filmmaker responsible for “Carrie,” “Dressed to Kill,” “Blow Out,” “Scarface,” “The Untouchables” and “Femme Fatale” serves not only as a guide to one of the most fascinating filmographies of our time, but a thoughtful and often hilarious look at the ups and downs of the American film industry over the last half-century, as seen through the eyes of one of its most idiosyncratic participants.

Born in Philadelphia in 1940, De Palma was a science guy until a viewing of Alfred Hitchcock’s “Vertigo”—which he considers to be not just one of the greatest films of all time, but a spot-on metaphor for the filmmaking process—inspired an interest in directing. After making a couple of award-winning shorts, he would make his first feature in 1963 with “The Wedding Party,” a film also notable for featuring the first lead performances from the then-unknown Robert De Niro and Jill Clayburgh. After a couple of additional documentary shorts, he would make another feature, the weird thriller “Murder a la Mod” (1968), before having his first taste of success with the underground hit “Greetings” (1968), a dark comedy that first brought to focus a number of elements that he would return to again and again throughout his career—voyeurism, conspiracies and assassinations among them. After the loose ‘Greetings” sequel “Hi Mom!” (1970), he would go off to Hollywood to make a studio version of a counter-culture comedy entitled “Get to Know Your Rabbit,” an experience so harrowing that it convinced De Palma that he would never make it working for the major studios.

After spending a few more years in the indie trenches making such films as the stylish horror hit “Sisters” (1973), the hilarious horror-musical-comedy “Phantom of the Paradise” (1974) and the “Vertigo” riff “Obesssion” (1976), De Palma decided it was time to try to channel his unique personal vision into something that a mass audience might also be able to embrace. The result was “Carrie” (1976), an adaptation of the Stephen King novel about a teenage outcast (Sissy Spacek in one of her finest performances) with astounding powers that she unleashes during a fatal trip to the prom. Merging his spellbinding cinematic technique (including his deft use of split-screen and slow-motion imagery) with a genuinely likable central character, he came up with a film that was embraced by critics and audiences alike and which contained one of the most unforgettable scares in screen history. After another telekinetic thriller, “The Fury” (1978) and the ultra-low-budget experiment “Home Movies” (1979), which he made as part of a filmmaking class he was teaching at Sarah Lawrence, he had another hit with the controversial thriller “Dressed to Kill” (1980), a film that took “Psycho” as its leaping-off point for one of his most audacious blends of sex, violence, dark humor, current events, technological advances (both mechanical and human) and spellbinding set pieces.

From that point on, however, De Palma’s oftentimes dark and overly violent and sexual works would find less favor in an increasingly conservative cinematic climate. There would be controversies such as the uproars over screen brutality inspired by “Scarface” (1983), “Body Double” (1984) and “Casualties of War” (1989). There would be box-office flops such as “Wise Guys” (1986), “The Bonfire of the Vanities” (1990), “Mission to Mars” (2000) and films that barely managed to get released like “Redacted” (2007) and “Passion” (2013). There would be a couple of huge hits in the big-screen adaptations of the television shows “The Untouchables” (1987) and “Mission: Impossible” (1996) and ones that deserved to better than they did like “Rasing Cain” (1992), “Carlito’s Way” (1993) and “Snake Eyes” 1998). There were even a couple of bonafide masterpieces as well in “Blow Out” (1981), a film that was rejected in the day for being a bleak thriller with an enormous downer of an ending but which is now regarded as his finest work, and “Femme Fatale” (2002), a run-through of his pet dramatic and stylistic obsessions that is perhaps the ultimate De Palma film.

In order to survive a career with such wild ups and downs, one needs a level head, a strong personal ethic and a keen sense of humor; in discussing his career (in footage culled from over 30 hours of footage shot by Noah Baumbach and Jake Paltrow), De Palma demonstrates that he has all three. He proves to be a perceptive observer of his own work who can explain what worked without sounding like a braggart and what didn’t without coming across as too apologetic. He manages to be both lucid and fascinating when discussing his particular stylistic and dramatic obsessions and never makes the mistake of getting bogged down in minutiae. And yes, he has plenty of stories to dish—some of which will be familiar to his more ardent fans (such as his disastrous first meeting with the legendary Bernard Herrmann regarding the scoring of “Sisters” and the time when he was offered, of all things, “Flashdance.”) Other stories may be unfamiliar, such as his account of battles with such writers as David Mamet, Oliver Stone and Robert Towne, and his decision to restructure “Raising Cain” after completing shooting. We even get to see such rare ephemera as snippets of the infamous stage musical version of “Carrie” and the massive hurricane that was originally intended to be the climax to “Snake Eyes.”

Watching De Palma talk about his own work is a joy—he proves to be a raconteur of the highest order—but he is just as fascinating when he offers the occasional observations about the film industry as a whole. There is a rueful yet nostalgic tone, for example, when he talks about the early days when he and his filmmaking pals first hit Hollywood and helped each other out when they could (he aided in the editing of the classic backroom conversation between De Niro and Harvey Keitel in Scorsese’s “Mean Streets”). He talks at length about trying to keep his personal vision intact in a studio system that frowns on such things and the sacrifices he was willing to make to do that, such as making his films exclusively in Europe in the wake of “Mission to Mars.” He astutely explains why most effects-heavy blockbusters are so dull these days—most of the big set pieces tend to be pre-visualized not by the director but by the effects crews putting them together who are more concerned with getting the effects to work than in giving them any sense of individual style. Speaking of analyzing mistakes, another highlight comes when he gleefully looks at the various permutations of “Carrie” that have come around in recent years and notes that many of the ideas and elements that he rejected as being too anti-cinematic ended up in the remakes, and demonstrated conclusively that he was right all along.

As far as I can tell, there is only one real flaw to be had in “De Palma.” In trying to cover nearly 30 feature films in two hours, some wind up getting a little bit of a short shrift—I would have liked a little more discussion of recent works like “Femme Fatale,” “The Black Dahlia,” “Redacted” and “Passion” than is afforded here. (De Palma sort of answers for this by suggesting that most filmmakers do their most significant works in their 30s, 40s and 50s.) There have been a lot of celebrity-based documentaries in recent years, but “De Palma” is not only one of the best, it is a rare one that is worthy of its subject matter. For De Palma fans, it is, of course, essential, but anyone with even the slightest interest in American cinema over the last fifty years and into the future will find it fascinating as well.