“Casualties of War” is a film based, we are told, on an actual event. A five-man patrol of American soldiers in Vietnam kidnapped a young woman from her village, forced her to march with them, and then raped her and killed her. One of the five refused to participate in the rape and murder, and it was his testimony that eventually brought the others to a military court martial and prison sentences. The movie is not so much about the event as about the atmosphere leading up to it – the dehumanizing reality of combat, the way it justifies brute force and penalizes those who would try to live by a higher standard.

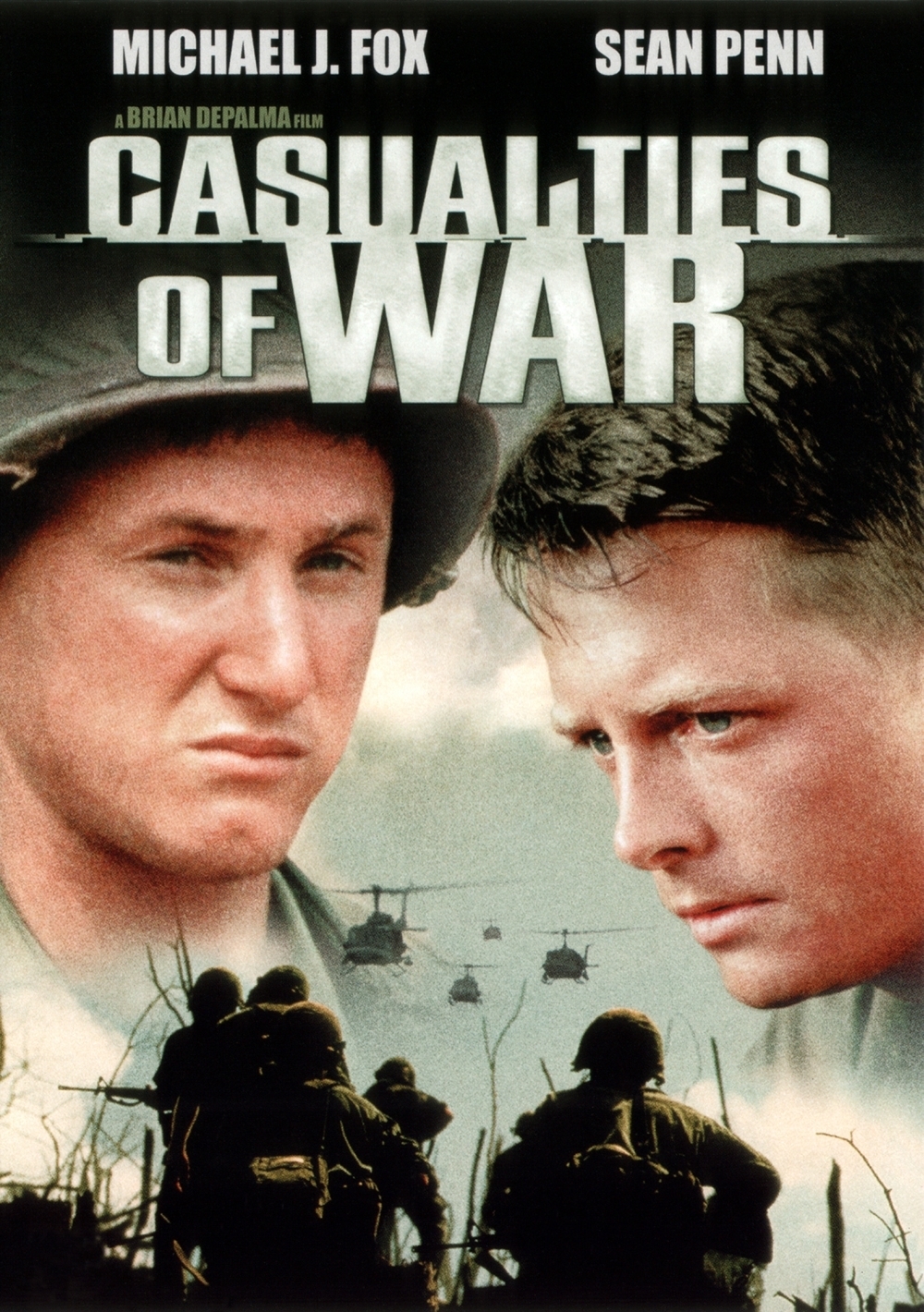

The film begins as Eriksson, a young infantryman (Michael J. Fox), arrives in Vietnam and is assigned to a unit filled with veterans. They’ve been in combat, on and off, for months, and Meserve, the sergeant (Sean Penn), is a short-timer with less than a month to go before he can return home. Meserve is a good soldier, strong, violent and effective. He is capable of heroism and has leadership ability. But he has lost, or he never had, the fundamental moral standards that most of us would like to believe are a product of his, and our, civilization.

On the night before he is scheduled to lead his men on a long-range reconnaissance patrol, Meserve is prevented by the MPs from going to a nearby village where he plans to visit a prostitute.

Enraged, he involves his men in a plan to enter the village secretly and kidnap a young woman (not a prostitute), who will be brought along on the mission to service the sexual needs of all five men. When he explains this plan, Eriksson, the Fox character, doesn’t believe he really means it. But he means it, all right.

In the field, the five men break into two groups: Eriksson and Diaz, who make a private agreement to “support” each other in refusing to go along with the rape, and the other three men, who are gung-ho in favor of it. Meserve is the ringleader, and is played by Penn with such raw, focused power that it is easy to see how a weak person would be intimidated by him. Penn has a denial system that allows him to describe the kidnapped girl as a “Viet Cong prisoner,” but actually he isn’t even very concerned about justifying what he’s doing. “What happens in the bush stays in the bush,” one says.

When the actual moment of the gang rape arrives, Eriksson refuses to go along. He tries, in a tentative and agonizing way, to argue that “this isn’t what it’s supposed to be about, over here.” Meserve lashes him verbally: He is not loyal to the group, he loves the Cong, he’s probably a queer, and so on. Diaz, hearing this, refuses to support Eriksson’s stand. Four of the men rape the girl, and later the same four pump bullets into her.

This whole sequence of scenes is harrowing because it makes it so clear how impotent Eriksson’s moral values are in the face of a rifle barrel. The other men either never had any qualms about what they are doing, or have lost them in the brutalizing process of combat. They will do exactly what they want to do, and Eriksson is essentially powerless to stop them. The movie makes it clear that when a group dynamic of this sort is at work, there is perhaps literally nothing that a “good” person can do to interrupt it. And its examination of the realities of the situation is what’s best about the movie.

What is not so good are the scenes before and after the powerful central material. The movie begins and ends some time after the war, with the Fox character on a train – where he sees an Asian woman who reminds him of the victim. The dialogue he has with this woman in the movie’s last scene is so forced and unnatural and tries so hard to cobble an upbeat ending onto a tragic story, that it seems to belong in another movie. I also felt that the aftermath of the crime – Eriksson’s attempts to bring charges – developed unevenly.

Confrontations with two commanding officers are effective (they explain, obscenely and profanely, why he has no business pressing charges), but then the outcome seems sketchy and tacked on. Perhaps the movie would have been more effective if it had just recorded the incident and ended as the group returned to base. That much would have contained everything important that the movie has to say. The narrative sandwich around it is simply distracting.

“Casualties of War,” written by the playwright David Rabe, is the first film by director Brian De Palma since “The Untouchables.” More than most films, it depends on the strength of its performances for its effect – and especially on Penn’s performance. If he is not able to convince us of his power, his rage and his contempt for the life of the girl, the movie would not work. He does, in a performance of overwhelming, brutal power. Fox, as his target, plays a character most of us could probably identify with, the person to whom rape or murder is unthinkable, but who has never had to test his values in the crucible of violence. The movie’s message, I think, is that in combat human values are lost and animal instincts are reinforced. We knew that already. But the movie makes it inescapable, especially when we reflect that the story is true, and the victim was real.