I had not read the autobiography of Chuck Barris when I went to see “Confessions of a Dangerous Mind.” Well, how many people have? So I made an understandable error. When the movie claimed that the game show creator had moonlighted as a CIA hit man, I thought I was detecting a nudge from the screenwriter, Charlie Kaufman. He is the man who created the portal into John Malkovich‘s mind in “Being John Malkovich” and gave himself a twin brother in “Adaptation.” Now, I thought, the little trickster had juiced up the Barris biopic by making the creator of “The Gong Show” into an assassin. What a card.

I am now better informed. Barris himself claims to have killed 33 times for the CIA. It’s in his book. He had the perfect cover: The creator of “The Dating Game” and “The Gong Show” would accompany his lucky winners on trips to romantic spots such as Helsinki in midwinter and kill for the CIA while the winners regaled each other with reindeer steaks. Who, after all, would ever suspect him? When I met Barris I asked him, as everyone does, if this story is true. He declined to answer. The book and the movie speak for themselves–or don’t speak for themselves, depending on your frame of mind. As for myself, I think he made it all up and never killed anybody. Having been involved in a weekly television show myself, I know for a melancholy fact that there is just not enough time between tapings to fly off to Helsinki and kill for my government.

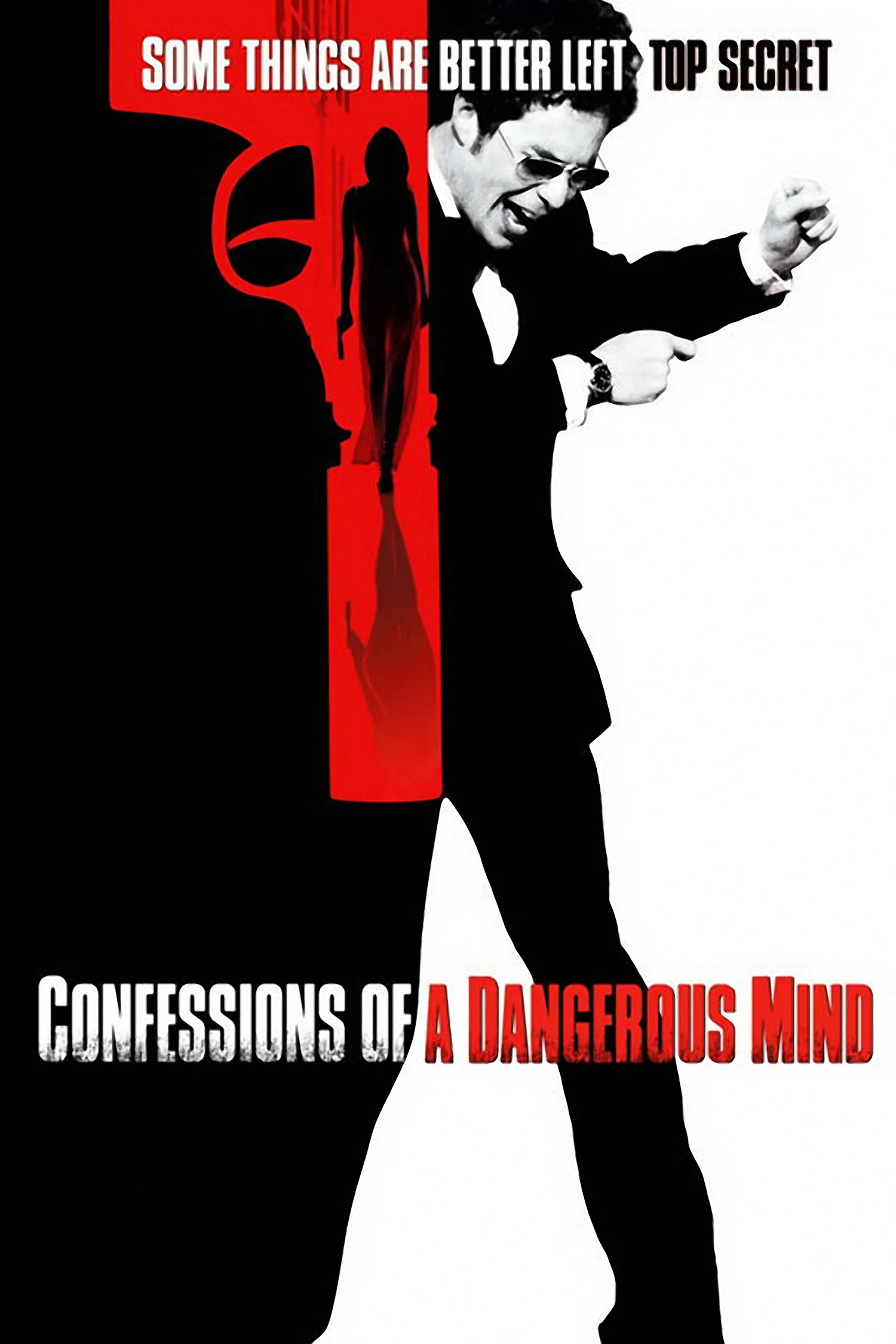

It matters not whether the story is true, because all autobiographies are fictional, made up out of that continuous subconscious rewriting process by which we make ourselves blameless and heroic. Barris has a particular need to be heroic, because he blamed himself for so much. As the movie opens in 1981, he is holed up in a New York hotel, mired in self-contempt and watching TV as his penance. It is here, he tells us in a confiding voiceover, that he began to record “my wasted life.” That this would be the first project to attract George Clooney as a director is not so surprising if you know that his father directed game shows, and he was often a backstage observer. That Clooney would direct it so well is a little surprising, and is part of that re-education by which we stop thinking of Clooney as a TV hunk and realize he is smart and curious. His first movie is not only intriguing as a story but great to look at, a marriage of bright pop images from the 1960s and 1970s and dark, cold spyscapes that seem to have wandered in from John le Carré .

Sam Rockwell plays Barris as a man who was given gifts but not the ability to enjoy them. He is depressed not so much because he thinks he could have done better in his life, but because he fears he could not. From his start as an NBC page in 1955, through his backstage work on Dick Clark’s “American Bandstand,” to the crushing blow of having ABC choose “Hootenanny” over his “Dating Game” pilot, Barris comes across as a man who wants to succeed in order to confirm his low opinion of himself. When his shows finally make the air, the TV critics blame him for the destruction of Western civilization, and he doesn’t think they’re so far off.

The movie has fun with the TV shows. We are reminded once again of the Unknown Comic and Gene Gene the Dancing Machine, and on an episode of “The Dating Game” we see a contestant choose Bachelor No. 3 when we can see that Bachelors 1 and 2 are Brad Pitt and Matt Damon. Early in his career, Barris is recruited by a CIA man named Jim Byrd (Clooney) and agrees to become a secret agent, maybe as a way of justifying his existence. “Think of it as a hobby,” Byrd says soothingly. “You’re an assassination enthusiast.” Two other women figure strongly in his life. Patricia Watson (Julia Roberts) is the CIA’s Marlene Dietrich, her face sexily shadowed at a rendezvous. She gives him a quote from Nietzsche that could serve as his motto: “The man who despises himself still respects himself as he who despises.” And then there’s Penny (Drew Barrymore), the hippie chick who comes along at first for the ride and remains to be his loyal friend, trying to talk him out of that hotel room.

“Confessions of a Dangerous Mind” makes a companion to Paul Schrader’s “Auto Focus,” the story of the rise and fall of “Hogan’s Heroes” star Bob Crane. Both films show men whose secret lives are more exciting than the public lives that win them fame. Barris seems to want to redeem himself for the crimes he committed on television, while Crane uses his fame as a ticket to sex addiction.

Both films lift up the cheerful rock of television to find wormy things crawling for cover. The difference is that Crane comes across as shallow and pathetic, while Barris–well, any man who would claim 33 killings as a way to rehabilitate his reputation deserves our sympathy and maybe our forgiveness.