Eddie Cantor once told Bob Crane, “likability is 90 percent of the battle.” It seems to be 100 percent of Bob Crane’s battle; there is nothing there except likability–no values, no self-awareness, no judgment, no perspective, not even an instinct for survival. Just likability, and the need to be liked in a sexual way every single day. Paul Schrader‘s “Auto Focus,” based on Crane’s life, is a deep portrait of a shallow man, lonely and empty, going through the motions of having a good time.

The broad outlines of Crane’s rise and fall are well known. How he was a Los Angeles DJ who became a TV star after being cast in the lead of “Hogan’s Heroes,” a comedy set in a Nazi prison camp. How his career tanked after the show left the air. How he toured on the dinner theater circuit, destroyed two marriages, and was so addicted to sex that his life was scandalous even by Hollywood standards. How he was found bludgeoned to death in 1978 in a Scottsdale, Ariz., motel room.

Crane is survived by four children, including sons from his first and second marriages who differ in an almost biblical way, the older appearing in this movie, the younger threatening a lawsuit against it, yet running a Web site retailing his father’s sex life. So strange was Crane’s view of his behavior, so disconnected from reality, that I almost imagine he would have seen nothing wrong with his second son’s sales of photos and videotapes of his father having sex. “It’s healthy,” Crane argues in defense of his promiscuity, although we’re not sure if he really thinks that, or really thinks anything.

The movie is a hypnotic portrait of this sad, compulsive life. The director, Paul Schrader, is no stranger to stories about men trapped in sexual miscalculation; he wrote “Taxi Driver” and wrote and directed “American Gigolo.” He sees Crane as an empty vessel, filled first with fame and then with desire. Because he was on TV, he finds that women want to sleep with him, and seems to oblige them almost out of good manners. There is no lust or passion in this film, only mechanical courtship followed by desultory sex. You can catch the women looking at him and asking themselves if there is anybody at home. Even his wives are puzzled.

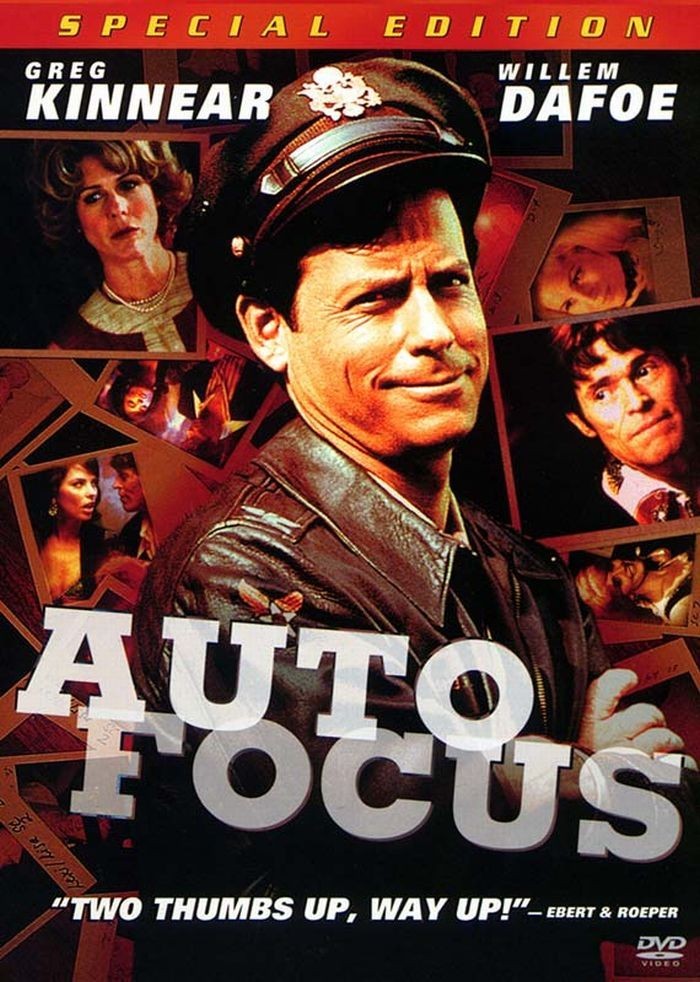

Greg Kinnear gives a creepy, brilliant performance as a man lacking in all insight. He has the likability part down pat. There is a scene in a nightclub where Crane asks the bartender to turn the TV to a rerun of “Hogan’s Heroes.” When a woman realizes that Hogan himself is in the room, notice how impeccable Kinnear’s timing and manner are, as he fakes false modesty and pretends to be flattered by her attention. Crane was not a complex man, but that should not blind us to the subtlety and complexity of Kinnear’s performance.

Willem Dafoe is the co-star, as John Carpenter, a tech-head in the days when Hollywood was just learning that television could be taped and replayed by devices in the consumer price range. Carpenter hangs around sets flattering the stars, lending them the newest Sony gadgets, wiring their cars for stereo and their dressing rooms for instant replays. He is the very embodiment of Mephistopheles, offering Crane exactly what he wants to be offered.

The turning point in Crane’s life comes on a night when Carpenter invites him to a strip club. Crane is proud of his drumming, and Carpenter suggests that the star could “sit in” with the house band. Soon Crane is sitting in at strip clubs every night of the week, returning late or not at all to his first wife Anne (Rita Wilson). Sensing something is wrong, he meets a priest one morning for breakfast, but is somehow not interested when the priest suggests he could “sit in” with a parish musical group.

Dafoe plays Carpenter as ingratiating, complimentary, sly, seductive and enigmatically needy. Despite their denials, is there something homosexual in their relationship? The two men become constant companions, apart from a little tiff when Crane examines a video and notices Carpenter’s hand in the wrong place. “It’s an orgy!” Carpenter explains, and soon the men are on the prowl again. The video equipment has a curious relevance to their sexual activities; do they have sex for its own sake, or to record it for later editing and viewing? From its earliest days, home video has had an intimate buried relationship with sex. If Tommy Lee and Pamela Anderson ever think to ask themselves why they taped their wedding night, this movie might suggest some answers.

The film is wall-to-wall with sex, but contains no eroticism. The women are never really in focus. They drift in and out of range, as the two men hunt through swinger’s magazines, attend swapping parties, haunt strip clubs and troll themselves like bait through bars. If there is a shadow on their idyll, it is that Crane condescends to Carpenter, and does not understand the other man’s desperate need for recognition.

The film is pitch-perfect in its decor, music, clothes, cars, language and values. It takes place during those heady years between the introduction of the Pill and the specter of AIDS, when men shaped as adolescents by Playboy in the 1950s now found some of their fantasies within reach. The movie understands how celebrity can make women available–and how, for some men, it is impossible to say no to an available woman. They are hard-wired, and judgment has nothing to do with it. We can feel sorry for Bob Crane but in a strange way, because he is so clueless, it is hard to blame him; we are reminded of the old joke in which God tells Adam he has a brain and a penis, but only enough blood to operate one of them at a time.

The movie’s moral counterpoint is provided by Ron Leibman, as Lenny, Crane’s manager. He gets him the job on “Hogan’s Heroes” and even, improbably, the lead in a Disney film named “Superdad.” But Crane is reckless in the way he allows photographs and tapes of his sexual performances to float out of his control. On the Disney set one day, Lenny visits to warn Crane about his notorious behavior, but Crane can’t hear him, can’t listen. He drifts toward his doom, unconscious, lost in a sexual fog.