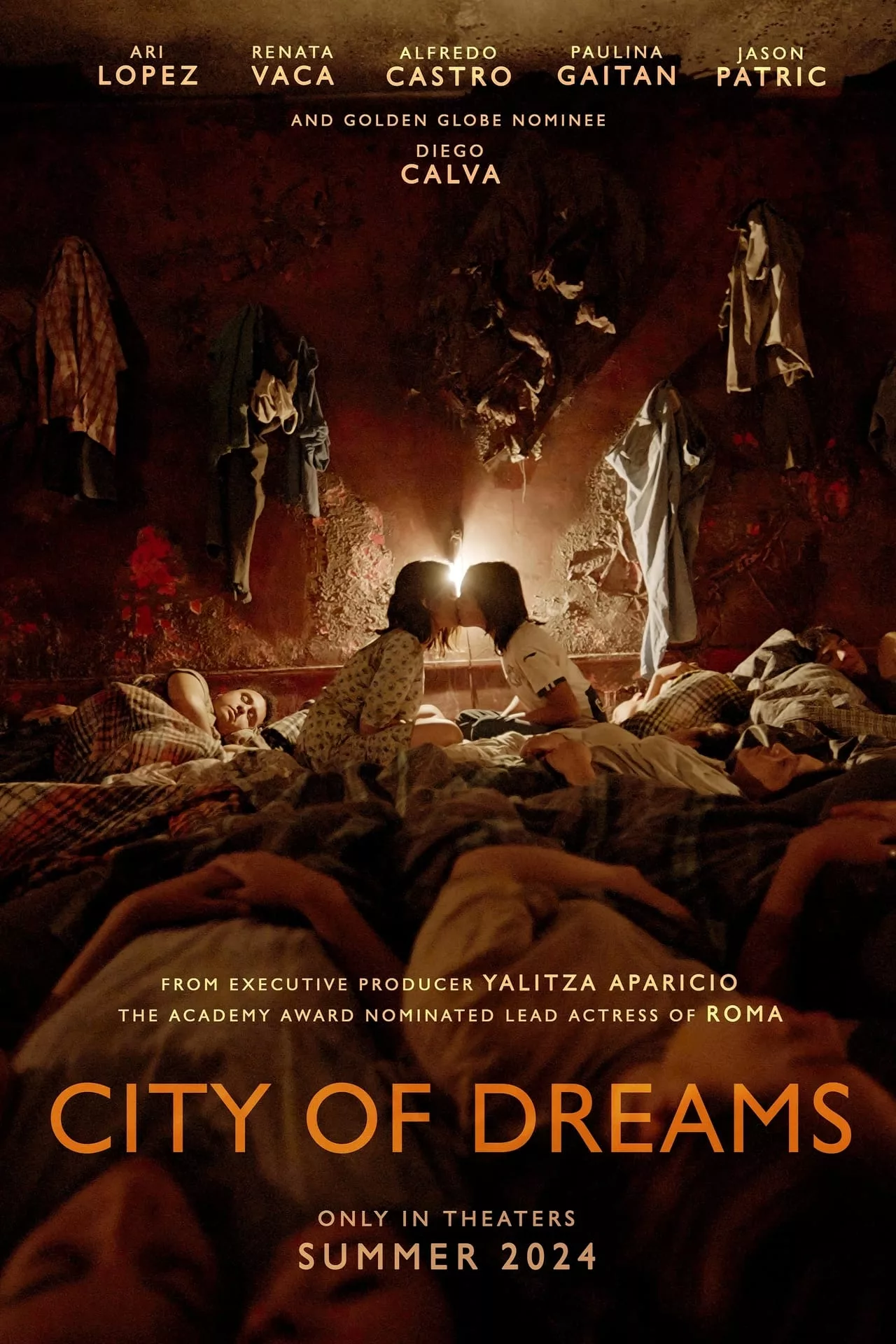

“City of Dreams” is a movie with a mission: to raise awareness about child trafficking. However, as a work of fiction “inspired by true events,” it leaves much to be desired. It is a sensationalized portrait of the problem, the kind of movie that doesn’t pull at the heartstrings so much as it takes a jackhammer to them. A not insignificant portion of the run time is dedicated to watching a child beaten over and over again as overlong close-ups capture every tear he sheds. But for what reason? At the end of this tortuous road, we are no wiser about the issue, given no instructions on how to help a boy in this situation, merely directed to a website that promotes the film and how you, the audience, should tell others to watch it. There are no resources for survivors, no links to advocacy groups or foundations doing the on-the-ground work of helping trafficking survivors. If the purpose of this movie is to raise awareness but not do anything, mission accomplished.

In the film, Jesús (Ari Lopez) is a young boy with dreams of playing professional soccer. He lives in a part of Mexico far from the shining lights of big stadiums, but a pamphlet for a soccer camp in Los Angeles gives him hope to chase his dreams. His father sends him north with a flamboyant coyote with a badly-gelled ‘do, flashy shirt, and sports car. The stranger promises a new life, but it’s not the kind Jesús dreamed of when he wakes up in Los Angeles. He learns that he has been bought and sold to a windowless sweatshop with no hope of escape or a chance at pursuing his dream.

Mohit Ramchandani’s feature debut paints a bleak picture with few moments of reprieve, practically guilting the audience into submission by the time the movie ends with a PSA calling out the rich and famous (including activists like Angelina Jolie and Bono) as well as politicians from both sides of the aisle (Hillary and Bill Clinton, Barack Obama, Donald Trump, and Florida Governor Ron DeSantis) for their inaction on the issue. However, this message gets muddled in the movie when Ramchandani’s script focuses so intensely on the dangers facing Jesús. “City of Dreams” only briefly shows us glimpses of our character’s past and goals before plunging the audience into the child’s kidnapping, forced labor, and mental and physical abuse at the hands of a cruel taskmaster known as El Jefe (Alfredo Castro) and his nephew Cesar (Andrés Delgado). The abuse of Jesús felt so gratuitous it brought to mind the use of violence in Mel Gibson’s “The Passion of the Christ” as well as the question of whether or not seeing this fictional violence helps the audience better understand its message or is it merely used to shock them? After all, what is the point of a “Final Destination”-like scare when Jesús is almost stabbed in the eye by El Jefe with a nail in a floorboard if not to jolt the audience with suspense?

“City of Dreams” feels like the tabloid treatment of the topic, emphasizing certain details over straightforward reporting. The story is built up to be a thriller, complete with a stylish long take chase sequence through Los Angeles’ Fashion District, tense showdowns between our hero and his captors, and cops streaming in to save the day and cart off El Jefe as he screams “This is America!” The film also feels strangely hostile towards Latinos, showing us as complicit in our children’s abuse and using a recurring vision of men in indigenous regalia haunting Jesús, which seems to suggest that old cultural (non-Christian) practices caused his mother’s death. In addition to forced labor trafficking, the movie hints at the threat of sex trafficking when a stylish wraith-like figure enters the sweatshop to take girls like Jesús’ only friend and first love, Elena (Renata Vaca), for nefarious purposes. It’s noteworthy that Jesús is effectively silent for most of the movie, bluntly symbolizing his lack of voice and agency until he is rescued from these conditions and, in the arms of one of the officers who saved him, speaks his first words. But the movie stops at a crucial point in a survivor’s journey when they emerge from the horrific ordeal. It leaves us with a close-up of Jesús’ crying face as the sound of a roaring crowd chanting his name grows louder. It provides no answers as to what will happen to him next: if he’ll be deported or punished for trying to seek out a better life like millions of children before him.

It is not necessary to show child abuse for the sake of entertainment to condemn it. Yet “City of Dreams” leaves so much left unsaid when it comes to this issue, like the apprehension of going to the police for help because that might get someone deported or arrested, that creates such an incomplete picture, it feels irresponsible. Much like “Sound of Freedom” before it, “City of Dreams” also hinges on a white savior (Jason Patric, who plays an overzealous officer who runs headfirst into a conspiracy stopping justice from saving these kids) and focuses more attention on the movie’s success than the issue itself. It’s disingenuous to claim “save the children” when one of the executive producers of the film has received allegations of abuse and sexual misconduct at a time when states across the country are attempting to dismantle child labor laws and calls to further militarize the border doesn’t help people in Jesús’ predicament. The movie is cruel, manipulative, visually and narratively mediocre, ethically questionable at best, and offers no resources for a path forward. It is another advocacy film without answers, pretending that the mere act of bringing awareness to a problem solves it.