Scene: A woman stands in a small courtyard. It is a snowy night. A film actress, she has come home to visit her mother and adopted daughter. She meets up with her lover of four years, an irresponsible playboy. His parents forbid them to get married, but they can’t seem to break up either. Out in the courtyard, she paces. Then, suddenly, she lies face-down in the snow. It looks like she’s trying to sink into the ground. Then she crooks out her left arm a little bit, her hand scooping around underneath. Since there’s no dialogue, we are left to interpret this on our own. Despair? Hopelessness? Is she ill?

The scene shifts abruptly to a grainy black-and-white film strip, where a woman, another woman, lies collapsed in the snow, clutching a baby in her left arm. A title comes on the screen: “‘Wild Flowers By the Road,’ 1930, directed by Sun Yu. Film no longer available.”

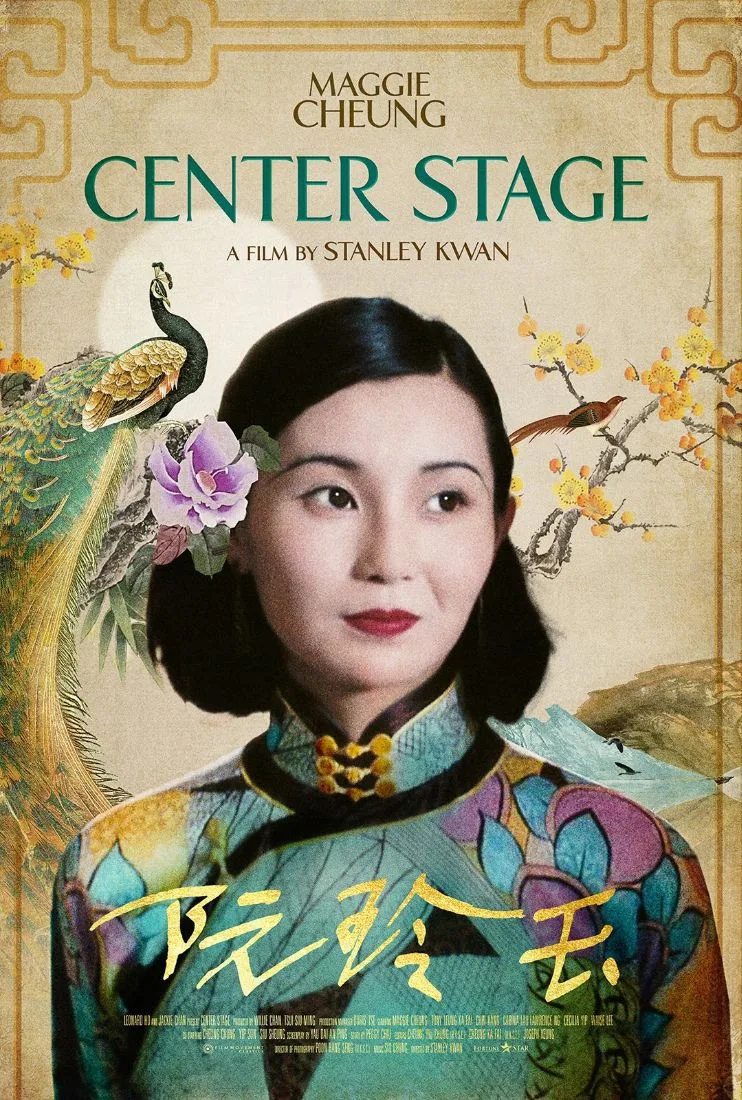

This sequence comes early on in Hong Kong director Stanley Kwan‘s 1991 masterpiece “Center Stage,” detailing the short intense life of legendary Chinese silent film star Ruan Lingyu, often referred to as “The Chinese Greta Garbo” (the title of Maire-Laure de Shazer’s 2017 biography of Ruan is The Beauty Of Shanghai – Ruan Ling Yu: The Chinese Greta Garbo.)

When the silent film interrupts the courtyard scene, the light of understanding comes with it. The second scene is actual footage of the real Ruan in the real movie “Wild Flowers By the Road,” and the first scene is Maggie Cheung, as Ruan, practicing the scene in the movie Ruan will soon have to perform. This is why Cheung’s left arm was positioned the way it was: she was holding an imaginary baby. The first scene is not a woman worrying about her love life, as it seems to be at first, but an actress at work. No wonder the film’s alternate title is “Actress.”

It’s an exhilarating sequence, particularly if you find the typical structure of most biopics frustrating and shallow (more on that in a moment). “Center Stage” is a maze of meta-mirrors, blending documentary footage into the narrative. But that’s just one aspect of the film’s hybrid style. There is “backstage” footage of group discussions involving Kwan and Cheung, and other cast members like Tony Leung, who plays director Tsai Chu-sheng, and Carina Lau who plays actress Lily-Li. They talk about the characters, they try to find points of connections, they attempt to parse out motivations. Kwan and the cast also seek out the real-life people (if they are still alive) and conduct interviews about their experiences. All of that footage is included too. Then the film goes back to the narrative, and we—now armed with deeper context—can engage with the film in a more profound way. Kwan constantly shows us why it all matters, and what exactly he and his cast are trying to express. He wants to leave nothing up to chance. The film itself says: I will show you how to watch me. Pay attention.

All of this may sound forbiddingly intellectual, or even annoying, in that the action is constantly interrupted by commentary on itself. Some critics at the time complained. (“‘Center Stage’ is a curiously uninvolving movie … It’s just plain hard to care.”) This critic missed the point. Bertolt Brecht used the “distancing” or “alienation” effect in his plays not because he didn’t want audiences to respond. Of course he wanted them to respond, but he wanted a specific kind of response, and he wanted to forbid unwelcome responses. He didn’t care if it was “plain hard to care” about the characters. In fact, Brecht’s goal was to hinder audience identification with the characters. He wanted people to not just feel, but think. This is what Kwan wants, too: he includes us in his process. In so doing, he reveals his obsession for the subject, removing us slightly from Ruan’s journey into his own. So many biopics are boilerplate, taking what I call the “and then this happened and then this happened and then this happened” approach. Kwan interrupts the flow.

Ruan Lingyu, born in 1911, is an icon in China, a celebrated legend of silent film. The tabloid coverage of her complicated love life was her undoing. Gossip was rampant and Ruan could not live with the shame. In 1935 she committed suicide by overdosing on barbiturates. She was just 24 years old. In between 1927 and her death, she made 30 films, many of which have been lost, although some have survived (either fully or partially). One was found as recently as 1994. But even with this tiny catalog, what we do have shows Ruan’s gift. At first she played what she called “wallflower roles,” before moving into more politically-driven progressive material, showing China’s “new woman.” She was prized for her realistic performances, and for how much she, as an actress, cared about realism (that courtyard scene again, with Ruan lying in the snow pretending to carry a baby, so she could know what it felt like). As mentioned, Ruan was often compared to Garbo, or sometimes Marlene Dietrich, but her performances in “The Goddess” or “The New Women” are suggestive more of Depression-era actress Sylvia Sidney, nearly forgotten now, but once a leading lady known for her sensitive portrayals of working-class women struggling to haul themselves out of the streets. Sidney’s persona was extremely down-to-earth, what we might call “relatable,” and when her gigantic eyes trembled with tears, audience hearts reached out to her. Ruan’s performances are similar. Kwan says in one of the rap sessions with his cast, “One of Ruan’s favorite expressions was looking up to the heavens in forlorn wordlessness.” Even with those heavenward glances, Ruan seems very much “of this earth” and so her work still feels very contemporary. (A couple of Ruan’s films can be viewed on YouTube.)

In “Center Stage,” Ruan says, “Acting is like madness. Actors are madmen. I’m one of them.” In many scenes, Ruan is shown creating some of her most famous roles. In “New Women,” there’s a scene where her character, a prostitute, lies in a hospital bed, wailing, “I want to live! I want to retaliate!” “New Women” was filmed in 1935, when Ruan’s life was falling apart. Paparazzi squat outside her house, making her a prisoner. She sees no way out. She only has a couple months left to live. And so Ruan has a difficult time screaming, “I want to live!” in her own hour of darkness. Kwan shows us the multiple takes necessary to get the moment right, with Cheung, ghostly-pale, looking wretchedly unhappy, brilliant in suggesting Ruan’s resistance to the moment. After she finally “nails” it in a heart-rending explosion, she hides under the sheet, sobbing uncontrollably, as crew members walk away, awkwardly leaving the actress in her misery. Kwan’s alienation effect is still present: As the scene ends, the camera pulls back even further, to show the crew of “Center Stage” standing around the bed, and Cheung says, “Tony, you forgot to lift up the sheet!”, scolding her co-star in “Center Stage,” Tony Leung, for forgetting an important part of business. So it’s Ruan and Cheung, simultaneously, and it’s Cheung playing Ruan playing the character in “New Women,” and Cheung “playing” herself in “Center Stage.” (Cheung won the Best Actress at the 1992 Berlinale for her performance.) The layers of artifice are multiple, and Kwan wants us present to all of them. He refuses to let us get too caught up in Ruan’s outburst, reminding us that none of it is real. He includes us in the project as co-creators, co-questioners, co-investigators.

For me, “Center Stage” has always been at the top of the heap of biopics, the measuring stick by which I judge all others, ever since I first saw it in 1995 at the Music Box in Chicago. With all of its discursions into documentary footage, interviews, and group discussions, “Center Stage” still tells Ruan’s story—and tells it beautifully—by surrounding Cheung with luscious Art Deco homes, and exquisite eye-catching interior decoration, gleaming cars, dark erotic nightclubs, the intense environment in which Ruan lived. The film’s structure admits, openly, that the truth can never be known. At the end of the day, all we can make are educated guesses. In his book King of the Jews, about early 20th century gangster Arnold Rothstein, Nick Tosches writes: “It isn’t the artful novelist who has blurred the divide between fiction and fact: It is the professor of learning, the peddler of secondhand misknowing. The more we ‘know,’ the less we know. It is better to keep away from words, ‘facts,’ ‘knowledge.’ They are almost always the carriers of disease.” Kwan and his cast go over and over the gaps in Ruan’s story, the unknown motivations, squinting into the past, imagining their way into Ruan’s world.

Real life is not linear. It is interrupted by switch-backs and awkward missing steps. People don’t see what’s clearly in front of their noses. They get caught up in the small stuff. Everyone knows this from their own lives. So many films, though, avoid mess like the plague. Biopics, particularly of artists, present specific challenges in this regard. They include too much. They leave too much out. They present the march towards fame as inevitable. They are uninterested in artistic process, in the hit-or-miss quality of an artist finding their way into maturity. Strangely, so many biopics do not address the only subject that really matters: Why do we care about this person? What did they do that was important and how did they do it? Biopics are fascinated by scandal, dwelling on drug addictions, bad marriages. It’s not that these things aren’t important, and it’s not that the negatives should be glossed over, but Billie Holiday’s music is more important than her drug addiction. Hank Williams’ overdose is the least interesting thing about him. Who was Hank Williams and why was his career important? Why are we all sitting in the seats? To gain a greater understanding into the artist in question. And yet so many biopics dance around these essential questions.

Eccentric approaches are sometimes more effective. “Love & Mercy,” about Brian Wilson of The Beach Boys, and Todd Haynes’ “I'm Not There,” about Bob Dylan, splintered the narrative, removing the pitfalls of linearity, and in so doing the films spend more time digging into the art, and the man who made the art. Tim Burton’s “Ed Wood,” shot in black and white, was a celebration of creativity and the “found family” aspect of show business, so key to putting Wood’s eccentric directorial career into context. Films like “8 Mile” or “The Rose” aren’t strictly biopics: they’re loosely-fictionalized versions of a well-known figure, but by releasing themselves from having to be factual, they can focus on what is important, which is why Eminem and Janis Joplin matter. “All That Jazz” is a completely sui generis biopic that basically creates its own category.

Stanley Kwan’s “Center Stage” also creates its own category. It is a biopic like no other. You come out of it with an appreciation for China’s early film history, and a respect for Ruan Lingyu, not just because of “what happened to her” in her life, but who she was as an actress. Ruan was so tormented by her personal life and by the public’s obsession with her personal life. A biopic that dwelled only on those salacious painful details would be repeating the same cycle. Kwan doesn’t skip over the two love affairs that put her reputation in jeopardy, but he puts the focus where it should be: her acting. What were Ruan’s qualities as an actress that made such an impact, not only on her contemporaries but, 60 years later, on Kwan who, even with an incomplete archive of films, is so obsessed he creates this towering tribute to her?

In his suicide note, Kurt Cobain wrote, “I don’t have the passion anymore, and so remember, it’s better to burn out than to fade away.” (How like a songwriter to quote a songwriter in his goodbye to the world.) Kwan and his cast discuss Ruan’s suicide along these lines. Cheung says, “She ended her career when she was at her pinnacle … And now she’s a legend.” The question of immortality dogs everyone. Kwan asks the group, “Is it advantageous for a movie star to vanish at the peak of her brilliance?”

These questions cannot be answered, and any answers given will be insufficient, incomplete, and ultimately un-interesting. “Center Stage,” pulsing with a heady blend of beauty, pain, and rigorous inquiry, follows Rainer Maria Rilke’s command to younger poets: “Live the questions.”