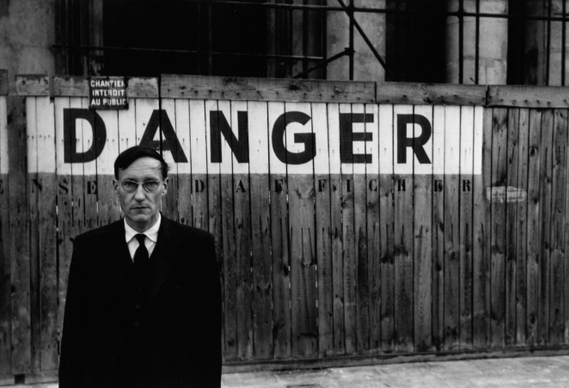

This is the man who wrote some of the most scandalous books of his time, although today the same taboos are broken on “Dynasty” and “Dallas.” His books included Naked Lunch, The Ticket that Exploded, Junkie and Exterminator. He was the godfather of the beatniks, he inspired Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg, and today whenever he gives a reading on a college campus or in a punk bar, the place is jammed with kids who cheer him as a survivor and a rebel.

“Burroughs,” opening today at Facets, is a documentary of the writer’s recent years. He walks through it in a series of business suits and neat fedora hats, and he is dispassionate for the most part. He has much to be dispassionate about. Born in St. Louis, educated at Harvard, briefly a medical student in Vienna, discharged from the U.S. Army, he spent the late 1940s as an exile in Tangiers, smoking hashish, shooting heroin, sniffing cocaine and “having a good time… although little did I know.”

Back in New York at Columbia University, he was introduced to his wife, Joan, by friends. “We thought,” says Allen Ginsberg in the film, “that they were equally talented, equally intelligent – a perfect match.” William and Joan found themselves in Mexico City a few years later where, Burroughs recounts, she grew depressed over his affairs with local boys and began to drink a bottle of tequila a day. One night during a drunken party, Burroughs suggested “our William Tell act” to his wife. She balanced a glass on her head, and his aim was good enough to hit her square in the forehead.

“It was just insanity,” he says dispassionately. The death was declared an accident, and Ginsberg helpfully notes that the incident seemed to trigger Burroughs’ writing: “That’s when he started to get the juices flowing.” So much for Joan. Burroughs went on to write in London and Paris. Many of his books first appeared in the notorious green-jacketed Olympia Press series from Paris, but eventually they could be sold openly in America, and as the beatniks became the hippies, Burroughs became some kind of counterculture saint.

Did that please him? The question is never asked. The most painful passages in the film deal with his son, Willie Jr., an alcoholic and speed freak – “the last of the beatniks” – who wrote a couple of books and then committed suicide during the filming. Father and son are awkward together; although they are both anti-establishment rebels, it gives them nothing in common.

“Burroughs” is a documentary portrait of a man who was willing to try everything, and who has so far survived everything. The one thing you miss in the film is the sound of laughter.