“Bad Lieutenant” tells the story of a man who is not comfortable inside his body or soul. He walks around filled with need and dread.

He is in the last stages of cocaine addiction, gulping booze to level off the drug high. His life is such a loveless hell that he buys sex just for the sensation of someone touching him, and his attention drifts even then, because there are so many demons pursuing him.

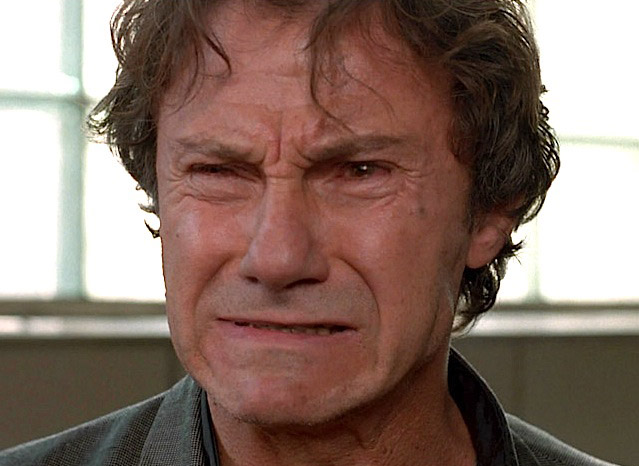

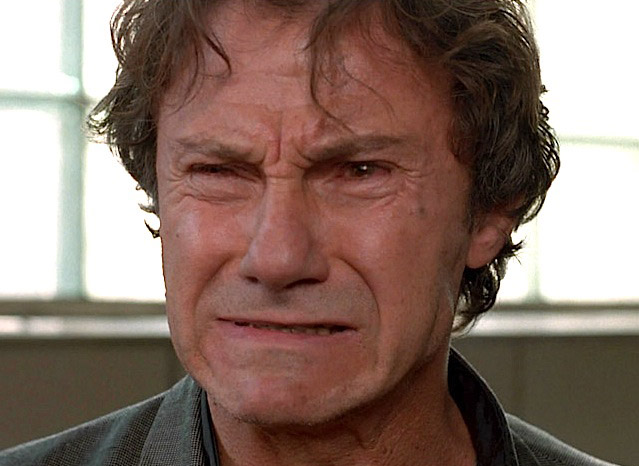

Harvey Keitel plays this man with such uncompromised honesty that the performance can only be called courageous; not many actors would want to be seen in this light.

The lieutenant has no illusions about himself. He is bad and knows he is bad, and he abuses the power of his position in every way he can. Interrupting a grocery store stickup, he sends the beat cop away and then steals the money from the thieves. He sells drug dealers their immunity by taking drugs from them. In the film’s most harrowing scene, he stops two teenage girls who are driving their parents’ car without permission. He threatens them with arrest, and then engages in an act of verbal rape.

Remember the Ray Liotta character in the last sequence of Martin Scorsese’s “GoodFellas,” when he is strung out on cocaine and paranoid that the cops are following him? His life speeds up, his thinking is frantic, he can run but he can’t hide. The Keitel character in “Bad Lieutenant” is like that other character, many more agonizing months down the road. Life cannot go on like this much longer.

We learn a few things about him. He still lives in a comfortable middle-class home, with a wife and three children who have long since made their adjustment to his madness. There is no longer a semblance of marriage. He comes in at dawn and collapses on the couch, to be wakened by the TV cartoons, which cut through his hangover. He stumbles out into the world again, to do more evil. When he drives the kids to school, his impatience is palpable; he cannot wait to drop them off and get a fix.

The movie does not give the lieutenant a name, because the human aspects of individual personality no longer matter at this stage; he is a bad cop, and those two words, expressing his moral state and his leverage in society, say everything that is still important about him.

A nun is raped. He visits the hospital to see her. She knows who attacked her, but will not name them, because she forgives them.

The lieutenant is stunned. He cannot imagine this level of absolution. If a woman can forgive such a crime, is redemption possible even for him? The film dips at times into madness. In a church, he hallucinates that Jesus Christ has appeared to him. He no longer knows for sure what the boundaries of reality are. His temporary remedies – drugs and hookers – have stopped working. All that remains are selfloathing, guilt, deep physical disquiet, and the hope of salvation.

“Bad Lieutenant” was directed by Abel Ferrara, a gritty New Yorker who has come up through the exploitation ranks (“Ms. 45,” “Fear City”) to low budget but ambitious films like “China Girl,” and “Cat Chaser.” This film lacks the polish of a more sophisticated director, but would have suffered from it. The film and the character live close to the streets. The screenplay is by Ferrara and Zoe Lund, who can be seen onscreen as a hooker. They are not interested in plot in the usual sense. There is no case to solve, no crime to stop, no bad guys except for the hero.

Keitel starred in Scorsese’s first film and has spent the last 25 years taking more chances with scripts and directors than any other major actor. He has the nerve to tackle roles like this, that other actors, even those with street images, would shy away from. He bares everything here – his body, yes, but also his weaknesses, his hungers. It is a performance given without reservation.

The film has the NC-17 rating, for adults only, and that is appropriate. But it is not a “dirty movie,” and in fact takes spirituality and morality more seriously than most films do. And in the bad lieutenant, Keitel has given us one of the great screen performances in recent years.