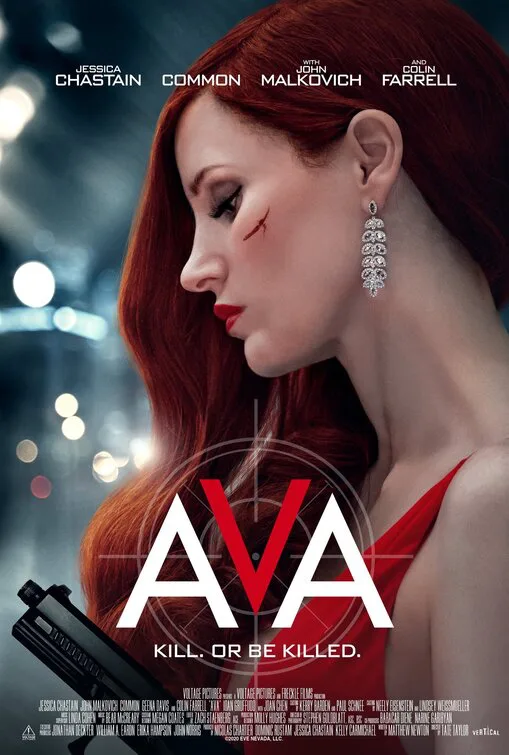

The Jessica Chastain vehicle “Ava” is not the movie you expect it to be, and that’s the source of its weaknesses as well as its strengths.

From a distance, “Ava” looks like it wants to be another female-driven action/spy thriller in the vein of “Atomic Blonde.” Set in glamorous international cities where targets need snuffing out, the movie mixes family drama; black comedy; luscious shots of four-star hotel suites, lobbies, and bars; and coldblooded espionage euphemisms that are meant to separate killers from their feelings (assassins tasked with murdering strangers are described as executives closing deals).

Yes, there is bloody action and plenty of it, though unfortunately it’s been directed by Tate Taylor (“The Help“) in the now-seemingly-mandatory handheld, cut-cut-cut style of post-Bourne action pictures. The only satisfying sequence is a close-quarters fight near the end that goes on and on until it becomes horrific, then exhausting, then funny. “I’m a bit rusty,” one combatant admits, blood streaming from his face.

But on the other hand—and here’s where “Ava” will lose viewers looking for the usual—the film’s heart belongs to its non-action scenes: simply staged face-offs between Chastain’s Ava, a recovering alcoholic and former teenaged delinquent, and supporting characters played by Geena Davis, Common, Joan Chen, Jess Weixler, John Malkovich, and other performers skilled enough to make words sting like slaps. (Ioan Gruffudd, a handsome actor who’s often cast as the slightly dull heroic lead, even shows up for couple of scenes as a scuzzbag money-mover, and seems to relish being free of the burden of nobility.)

The movie starts by establishing Ava as a talented but unstable “executive.” She’s adored by her grizzled mentor Duke (John Malkovich), a self-described father figure who replaced the bad biological dad who died when Ava was still a drunk. But she’s marked as a problem employee, thanks to her habit of getting her targets where she wants them, then pushing them to confess a bad thing they’ve done before “closing” them. It’s evidence of a latent moral streak that’s bubbling up in Ava after years of being tactically suppressed—and it’s bad for business. Another of Duke’s trainees, Simon (Colin Farrell, playing a murderous family man with a pornstar mustache and side-walled pompadour), is a rising star who’s being groomed as Duke’s replacement. He warns Duke that Ava has screwed up too oftenand is on deck to get “closed” by another “executive.” Duke can’t cover for Ava forever. Her bill will come due. Can Duke save her?

“Ava” never completely loses interest in its spy-world plot, but it becomes increasingly obvious that the actors and filmmakers are more invested in scenes where the characters talk to each other, poring over personal business and picking at emotional scabs. As I sit here writing this review, I’m having a hard time remembering any of the action scenes except for that last fight. But I have a photographic recall of scenes where Ava visits her ill mother Bobbi (Davis) in the hospital and reconnects with her estranged sister Judy (Wexler) and her husband Michael (Common).

Ava would be a prodigal daughter if anybody were happy to see her. She’s been AWOL from her family’s life due to substance abuse treatment and a packed international travel schedule (she tells her relatives that she works for the UN). There’s plainly some kind of secret, mortifying connection between Ava and Michael (you can tell by how they look at each other) that’ll be revealed in due time. Ava and Bobbi can barely open their mouths without hurting each other. Matthew Newton’s script has a keen ear for little throwaway lines that reveal dysfunction—as when Ava stands on a chair to fix a TV in Bobbi’s hospital room, and instead of “Thank you,” Bobbi says “Guess there was nothing wrong with it.”

The strongest scene in the film is a game of hearts between Ava and her mother, played at a small table against a window. Davis’ presence in the movie at first seems like a clever bit of meta-minded stunt casting: 26 years earlier, she starred in “The Long Kiss Goodnight,” an ahead-of-its-time crash-and-burn action flick about a female assassin named Charley Baltimore; Chastain’s wig in the first scene seems deliberately Charley-esque. But it soon becomes clear that Davis is in the cast because she’s a great actress and movie star. Bobbi dances around catharsis, refusing to give Ava the vulnerability she craves, then reversing herself, the floodgates opening. Chastain hangs back, letting Davis take the scene; what else can you do when your acting partner is doing some of the best work of her life? The actresses are so real here, and in all of the other Ava-Bobbi scenes, that you momentarily forget that this is the kind of film where people kill each other barehanded.

There’s also a rich (though underdeveloped) sub-theme having to do with addiction. Many characters in “Ava” are either addicts or in recovery, for everything from alcohol and drugs to gambling. It’s implied that the endorphin rush of extreme risk and sudden violence can amplify or partially replace whatever the assassins might do (or consume) elsewhere in their lives. Conversations between Duke and Simon make it clear that so-called “black ops” organizations hire addicted or addictive people because, having experienced chaos, or still being in the middle of it, they crave direction, attention, and approval. Even outwardly “normal” agency employees like Simon, with his big house and loving children, has a nihilistic or destructive streak that needs to be satisfied. And most of the ground-level killers like Ava and Joan Chen’s Toni are fringe-dwellers, existing in the margins of respectable society or beneath their radar (far beneath, in Toni’s case; she manages a secret nightclub and sex club with a hidden entrance disguised as a portable toilet).

“Ava” was marketed, half-assedly and without press screenings, as a hard-edged thriller with tons of gunplay and hand-to-hand combat, reminiscent of the intermittently excellent action pictures that Charlize Theron began to star in after turning 40. Whatever her motivation for saying yes to “Ava,” Chastain (who also coproduced) deserves credit for backing a project that does its own thing, seemingly without regard for what the audience wants, and that ends with a scene that’ll prompt “What the hell was that?” reactions. If the action and espionage elements were executed at the same level as the dramatic and comedic exchanges and the observations about the types of people drawn to this life, “Ava” might’ve been a cult classic.