I watched “All Day and A Night” on the anniversary of John Singleton’s death. This is relevant because Singleton crafted what I believe to be the ne plus ultra of this type of film. His success spawned a seemingly endless series of “hood movies,” of which I became extremely sick of watching. And this was almost 30 years ago. Hollywood’s Black movie greenlighting process is a pendulum that swings back and forth between slave movies and movies like this, both of which profit off our suffering while rarely having anything new to say or to add. Just when you think the flood of these movies appearing is over, it starts to rain. This is not to say that such movies should not exist, but do we have to get the same damn movie over and over?

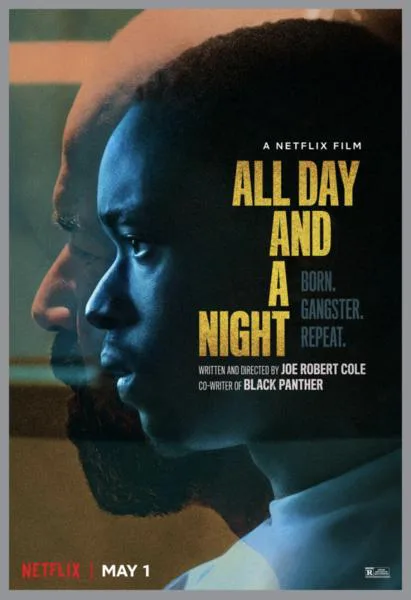

There is not a single original idea in “All Day and A Night.” Not one solitary surprise is to be had here. You don’t even need to watch it and I bet you will have guessed at least 95% of what happens based on the plot description and your knowledge of other movies. This film has been done too many times before and done better. For example, I kept being reminded of “Menace II Society.” The Hughes Brothers’ film is a major influence on writer/director Joe Robert Cole. You can see it in the plot details, the nonchalant depiction of casual violence, the flashback structure, the narration, the revenge killings and its bleak pessimism.

“Menace” was supposed to be a corrective of sorts to “Boyz N The Hood,” bleaching out any optimism that felt too cinematic. It’s a good film, but its mistake is its selective empathy—it asks you to feel for its doomed main character yet makes no such requirement for anyone else damaged in his path. Cole makes the same mistake here, but he is far less successful than the Hughes Brothers were. At least they had the terrifying unpredictability of O-Dog, Bill Duke’s unforgettable scene and the luxury of bending their clichés into a fresh perspective because their pioneering film was made 27 years ago.

Nowadays, this material is tired unless the movie can offer a different or more detailed take, one that imparts the filmmaker’s own vision rather than a carbon copy of what once worked. And there are movies out there that do this, that take a tragic story of struggle and hustling and elevate it above what came before. “Blindspotting” is a great example of this, as is “Fruitvale Station.” The latter film was made by Cole’s “Black Panther” co-writer Ryan Coogler and, like this one, both movies take place in Oakland, California. They also take the time to deeply interrogate the systemic causes for their characters’ actions and their pain.

At over two hours, “All Day and A Night” has plenty of time to do more than the surface-level once over it gives these elements. Instead, it substitutes a Cliffs Notes-style narration that sounds as bored as Harrison Ford’s in “Blade Runner.” The reciter of said narration is by Jah (Ashton Sanders), whom we first meet creeping through his neighborhood to crash the end of a house party. The camera follows him with feline grace and dexterity, promising a far more intriguing 122 minutes than we’ll get. Its journey ends with Jah pointing two guns at a man, woman and their young daughter. Jah executes the adults in front of her before the title card appears.

It’s here we realize that the film is going to randomly hop back and forth in time, damaging much of Jah’s story because it denies him any kind of emotional build up or dramatic arc. We know early on that he’s going to wind up in jail for this crime—next to his already-imprisoned father no less—and that the movie is going to withhold the reasons he did it as long as it can. Few films can successfully pull off a script that’s fragmented like this for no discernible reason. It’s frustrating, because when this is applied in a lazy fashion, it always feels like the movie played 52-pickup with its plot, opting to film scenes in whatever random order they landed. There is great power to be had in Jah’s story if the filmmakers had taken care to build momentum or even vise-like tension.

Jah’s life plays out in two timelines, the younger one finds him played by Jalyn Hall. Hall’s scenes are far more effective because they allow Jah to be more open and receptive, and we can see the things that harden him rather than just hear about them from the narration. These moments also benefit from a scary yet understated turn by Jeffrey Wright as Jah’s father, JD. When Jah is robbed and beaten up, JD beats him mercilessly before sending him back out to avenge the robbery. There’s method to JD’s madness—those kids will probably not rob Jah again after their beatdown—but the film gives it, and any other violent, male dominated philosophies on survival short shrift. It’s all described in the narration and then hastily discarded.

The women fare no better here. Elder Jah tells us in narration that mothers and grandmothers hold most families together in his neighborhood. However, Jah’s own mother is powerless in numerous scenes. There’s also a scene featuring the great character actor Regina Taylor as Jah’s grandma. She has little to do here except mildly chastise JD, almost invalidating Jah’s statement with her easy surrender. Now, compare this scene to the one in Spike Lee’s “Clockers” where the same actress puts Jah’s notion into action by fiercely protecting her ward at any cost. Action trumps lip service.

Much of “All Day and A Night” finds Jah running with dangerous company, a crew who works for neighborhood bigwig Big Stunna (Yahya Abdul-Mateen II). It’s he who gives Jah the guns to commit the opening murders. Abdul-Mateen is quite memorable here, so much so that I wanted to see more of the operation he and his female companion ran. They are the most “together” characters in the movie, as blasé about their business dealings as they were cunning. Jah’s running partner and Big Stunna’s employee, TQ (Isaiah John) teases him for working in a shoe store but supports his dreams of becoming a rapper. You already know what’s going to happen to both those rap dreams and Jah’s friendship.

The scenes with JD and Jah in prison don’t really register. They are clearly the film’s ultimate destination, but what exactly are we to glean from them? It appears that JD has little wisdom for Jah and neither Cole’s script nor his direction stick the landing vis-à-vis any kind of cautionary tale for Jah’s own son. For all of Cole’s comments about empathy in the press materials, “All Day and A Night” is terrified of its male characters showing weakness, fully embracing their sorrow or allowing us to care. What’s left is the type of derivative “hood movie” I remain tired of seeing and even more tired of reviewing. I grew up in the type of environment JD and Jah inhabit, and though there was hard times, violence and death, there was also joy, pleasure and even happiness. Unlike far too many movies of this ilk, we weren’t too afraid to show it.