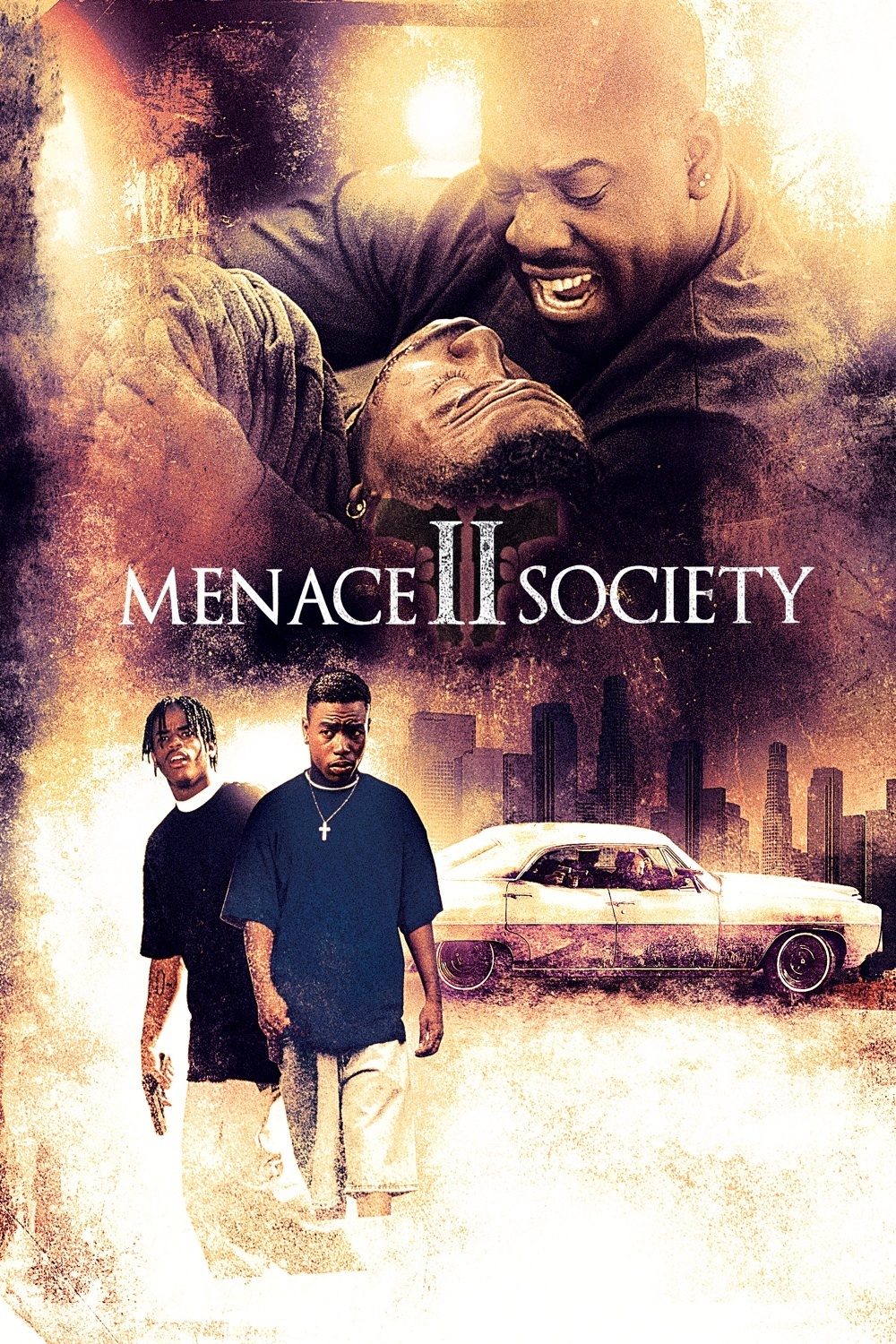

Caine, the young man at the center of “Menace II Society,” is not an evil person in the usual sense of the word. He has a good nature and a quick intelligence, and in another world he might have turned out happy and productive. But he was not raised in a world that allowed that side of his character to develop, and that is the whole point of this powerful film.

Caine, like so many young black men from the inner city, has grown up in a world where the strong values of an older generation are being undermined by the temptations of guns, drugs and violence.

As a small boy he sees his father murder a man over a trivial matter.

He sees his mother die of an overdose. He takes an older neighborhood man as his mentor, only to see him go to prison. By the time he is in high school, Caine wears a beeper on his belt and is a small-time drug dealer. The film’s narration tells us he is society’s nightmare: “He’s young, he’s black, and he doesn’t give a – – – -.” We see that it is more complicated than that. The tragedy of Caine’s life is that he cannot stand back a little and get a wider view, see what alternatives are available. He adopts the street values based on a corruption of the word “respect.” He wants respect but has done nothing to deserve it. For him, “respect” is the product of intimidation: If you back down because you fear him, you “respect” him.

The movie opens as Caine and O-Dog, his heedless, violent friend, enter a Korean grocery store to buy a couple of beers. The grocer and his wife, who don’t want trouble, ask them to make their purchase and leave. Caine and O-Dog engage in a little meaningless verbal intimidation, aware that because they are young and black they can score some points through the couple’s fear. “I feel bad for your mother,” the grocer says as they are about to leave. That is all O-Dog needs to hear, and he murders the grocer and then forces his wife to hand over the store’s security videotape before killing her, too.

Caine is shocked by this sudden violent development. He sees it in terms of his own misfortune: He went out to get a beer, and now he’s an accessory to murder. During the course of the movie, O-Dog will use the videotape for entertainment at parties, freeze-framing the moment of the grocer’s death. Eventually dozens of people will know who killed the grocer, but nobody will be charged with the crime, because such violence is so common and the laws are such that many murders simply slip through the fingers of the police.

There are people in Caine’s life who care for him. A friend who has an athletic scholarship. A teacher at school. His God-fearing grandparents, who eventually throw him out of the house. His mentor’s girlfriend, who wants him to move to Atlanta with her and start over.

But Caine’s world is narrow. He has the values of his immediate circle, and the lack of imagination: He cannot envision a world for himself outside of the limited existence of guns, cars, drugs and swagger. This movie, like many others, reminds us that murder is the leading cause of death among young black men. But it doesn’t blame the easy target of white racism for that: It looks unblinkingly at a street culture that offers its members few choices that are not self-destructive.

If “Boyz N the Hood” was the story of a young man lucky enough to grow up with parents who cared, and who escapes the dangers of the street culture, “Menace II Society” is, tragically, about many more young men who are not so lucky. The movie was directed by Allen and Albert Hughes, twin brothers, and is based on the screenplay they wrote with their friend, Tyger Williams. The brothers were 21 when they finished the film, but already they have a track record of many music videos. Their mother gave them a video camera when they were 12, they told me at the Cannes Film Festival, and that pointed them away from the possibilities they show in their film, and instead toward their current success.

The message here is obvious: Many victims of street violence are a great loss to society, their potential destroyed by a bankrupt value system. The Hughes twins, given a chance, reveal here that they are natural filmmakers. “Menace II Society” is as well-directed a film as you’ll see from America this year, an unsentimental and yet completely involving story of a young man who cannot see a way around his fate.

It’s impressive, the way the filmmakers tell Caine’s story without making him seem either the hero or victim; he is presented more as a typical example. We are not asked to sympathize with him, but to a degree we do, in the sense of the empathetic prayer, “There, but for the grace of God, go I.” It is clear that, given the realities of the society in which he is raised, Caine’s fate is a likely one.

The film is filled with terrific energy. The performances, especially those by Tyrin Turner as Caine, Larenz Tate as O-Dog, and Jada Pinkett, as Ronnie, the caring girlfriend, are filled with life and conviction. Because “Menace II Society” paints such an uncompromised picture and offers no easy hope or optimistic conclusion, it may be seen as a negative film in some quarters. “If you hate blacks, this movie will make you hate them more,” Allen Hughes said during his Cannes visit. “But true liberals will get something sparked in their heads.” That is true. If “Menace II Society” shows things the way they often are – and I believe it does – then the film is not negative for depicting them truthfully. Anyone who views this film thoughtfully must ask why our society makes guns easier to obtain and use than does any other country in the civilized world. And that is only the most obvious of the many questions the film inspires.