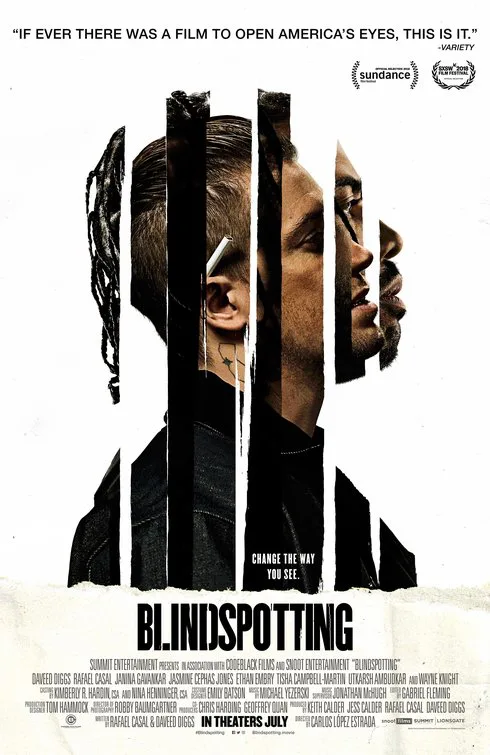

We are republishing this piece on the homepage in allegiance with a critical American movement that upholds Black voices. For a growing resource list with information on where you can donate, connect with activists, learn more about the protests, and find anti-racism reading, click here. “Blindspotting” is available this week for free rental via iTunes. #BlackLivesMatter.

“Blindspotting” is the third 2018 film to use Oakland, California as the jumping off point for the types of cinematic flights of fancy Hollywood rarely affords people of color. It is part of a trio that dares to violate an audience’s preconceived notions of what fates can befall Black and brown people onscreen, and how those outcomes are rendered. “Black Panther” made Oakland a sister city to the majestic fantasy that is Wakanda, achingly bridging the gap between Heaven and Earth. The more recent “Sorry to Bother You” presented an alternate reality Oakland where the struggle to survive veers sharply into science fiction.

By comparison, the plot of “Blindspotting” never delves into the surreal nor the fantastic; the film’s tone does this heavy lifting instead, shifting in unexpected ways that fracture reality while remaining stubbornly tethered to it. This movie swings between high drama and low comedy, and between terrifying danger and sweet moments of near-romance. Then it climaxes with an intense, brilliant monologue that is an almost otherworldly dare, a piece of performance art that some viewers are bound to question. Like all great movies, “Blindspotting” is a force to be reckoned with and wrestled with. No matter where you land in your assessment, your expectations are guaranteed to be shattered.

Watching this film, I was reminded of a quote from Chester Himes, the African-American crime fiction writer whose work quite often bent its tone in ways “Blindspotting” emulates. “And I thought I was writing realism,” Himes began. “It never occurred to me that I was writing absurdity. Realism and absurdity are so similar in the lives of American blacks one cannot tell the difference.” The ghost of Chester Himes makes himself known here in a story-within-this-story that recaps how Collin (Daveed Diggs) wound up serving the jail term for which he is currently paroled. Two gentlemen enter Collin’s current place of employment and recognize him as the former bar bouncer who delivered a legendary ass beating to an unruly, drunk patron. Director Carlos López Estrada shows us this beatdown, which is as fiercely hilarious and as graphically violent as anything found in Himes’ fiction.

At first, this scene seems merely tangential, but it becomes crucial to understanding the relationship between two of the film’s main characters, Collin and his ex-girlfriend Val (Janina Gavankar). In fact, much of “Blindspotting” feels haphazard and digressive; only upon retrospection does one realize how cleverly constructed and intricately woven together everything is. Much of that credit goes to the film’s co-stars and writers, Diggs and Rafael Casal, who plays Collin’s best friend, Miles. These two flesh out their characters’ idiosyncrasies in complicated ways while also interrogating the societal and personal tensions that hold their interracial friendship together against all odds.

Despite the aforementioned bouncer incident, Collin is presented as the calm one of the duo. He is three days from the end of his probation when “Blindspotting” opens, and he seems surrounded by elements custom-made for sending him back to prison. A casual meetup with Miles turns into a gun sale overseen by a mutual friend. As Collin freaks out in the backseat, mumbling his mantra of parole-saving “plausible deniability,” Miles flashes his new purchase with reckless abandon—it’s our first glance at the unspoken benefits of his privilege. Thankfully, their gun-selling friend’s car leaves the scene before any cops can show up. It seems that, in addition to providing illegal firearms, this guy’s an Uber. As the ‘hood changes, so must the side hustle.

And Oakland is changing, rapidly becoming gentrified by White hipsters and douchey tech bros not unlike the one who helped send Collin to prison. Miles and Collin both work for a moving company—Collin drives the truck, Miles navigates and they both split the manual labor—and it’s funny that they never move anyone into the neighborhood. Everyone seems to be leaving and, in the case of an artist played by Wayne Knight in a cameo, symbolically taking the city’s history with them. Knight’s art superimposes the oak trees that gave Oakland its name over the locations where they used to be. “Now they’re only on the street signs,” we’re told.

“Blindspotting” sees gentrification as an evil thing and it pushes that as a bigger irritant to Miles than to Collin. The new folks attempting to claim Oakland as their own look like Miles, and he considers that an affront to his own native rights to Oakland as someone who grew up there. Miles is a walking overcompensation, a White guy who sports a gold grill, is prone to reputation-proving violence and pitches his gangsta persona just a few notches higher than necessary in order to ensure his street cred. Casal plays him fully entrenched in this guise, which feels more like a sincere homage than the kind of cultural appropriation Miles fears deep down in his soul. At one point, Miles is driven to violence because someone mistakes him for the kind of gentrifier he despises.

In a lesser movie, the casting would be reversed and Miles would be the Sidekick Negro to the White lead character. But Diggs and Casal flip the script, imbuing Miles with the worry of coming off as what he perceives is a negative stereotype, a fear normally reserved for, and felt by, people of color. Miles wants to be down, but his privilege is the life preserver that will always keep him afloat. While one cannot deny his love and respect for the homeboy he’s known since they were eleven years old, Miles is still somewhat blind to how his actions may affect Collin, even after the aforementioned bar fight for which he loyally provided backup resulted in jail time only for Collin. Casal is commendably good here.

Diggs is also excellent in what may be the tougher role. Early in the film, Collin sees a fleeing Black man shot in the back by a pursuing White cop, and Diggs plays his reaction on both the cool level he presents to his friends and the tortured level that haunts him internally. “Blindspotting” plagues Collin visually with nightmarish dream sequences and morbid visions of the dead, but the film is even more effective when using the Oscar-worthy sound design to reflect Collin’s torment. The technical tricks evoke the awful truth that to be Black in America is to constantly exist in a state of perpetual post-traumatic stress disorder, knowing that even in moments of joy we are hyper-aware of our surroundings and the societal dangers that may arise from them even when they’re at their most benign. “Blindspotting” is daring enough to put the experiences of Miles and Collin on a collision course that forces a confrontation.

“Blindspotting” also finds time for Miles and Collin to interact with the women in their lives. Miles lives with Ashley (Jasmine Cephas Jones), with whom he has a young son. Collin works with Val, the former lover whose reasons for not rekindling their romance runs deeper than either of them will admit. Both actresses have a scene where they shine as brightly as their male leads: Ashley has an angry, honest kitchen table conversation with her irresponsible boyfriend; Val practices her psychology terms while braiding Collin’s hair (one of those terms gives the film its title). As a result, we want to see more of them, but at least the film brings them off the periphery every now and then to contribute to the story.

And then there’s that aforementioned climactic monologue, which allows Diggs to capitalize on the skilled mastery of wordplay that earned him the Tony for “Hamilton.” It is a leap of faith that, at least for me, is the most powerful scene of the year so far. It does not seem out of place; this ultimate response feels like the culmination of the film’s use of surrealism to heighten Collin’s emotional state. A fellow critic told me he could feel the audience resisting this sequence both times he saw the movie, but the small crowd with whom I saw “Blindspotting” was as enraptured as I was.

After the movie, a woman asked me and the gentleman she was with if we would have been friends with Miles. “HELL NO!” I told her, but then she challenged me to think about it. I realized that I have been friends with people like Miles, brash troublemakers who had my back and loved me even though they could have also gotten me killed or thrown in jail. “Realism and absurdity,” I thought to myself. My hasty emotional reaction, followed by my more calibrated introspection, is the equivalent of what it’s like to experience “Blindspotting.” This is one of the year’s best movies.

“Blindspotting” is available this week for free rental via iTunes.