The following is the second installment of “30 Minutes on:,” a new feature at the MZS blog wherein the author spends exactly 30 minutes writing about a movie, then hits publish.

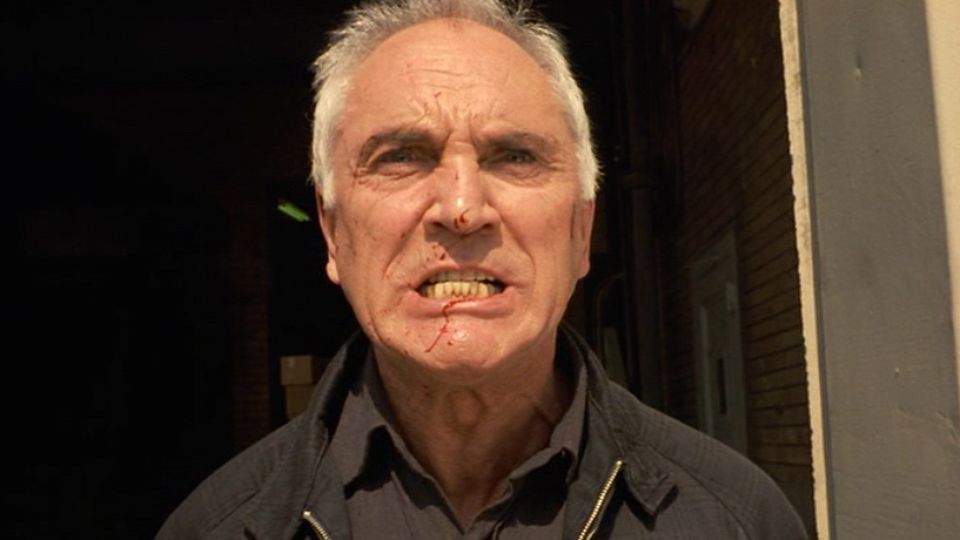

“Tell me about Jenny,” Terence Stamp’s ex-convict Wilson demands in the opening moments of “The Limey.” But what follows is a confession in the form of prismatic memory shards—a brain-teaser, at times flirting with midnight movie stoner pretension, that somehow keeps both its storyline and its emotions clear, and that also happens to fulfill the requirements of the revenge thriller, as well as the more rarefied genre of melodrama in which old men look back on life and take responsibility for their failures. All of these ambitions collide and fuse to form Steven Soderbergh’s masterpiece—his greatest film, hands-down, in nearly every department, but especially formal innovation, humor, icy hepcat style, and characterization as revealed through both dialogue and editing. All that, and it doesn’t overstay its welcome—another Soderbergh signature, but one that many of his contemporaries seem disinterested in emulating.

How did “The Limey” become “The Limey”? As circuitously and intuitively as “The Limey” tells the story of its title character, that’s how. The film was written by Lem Dobbs and then (if Dobbs’ contentious DVD commentary track is to be believed) rewritten by Soderbergh, and then directed by Soderbergh, and then rewritten again by Soderbergh in the cutting room along with his editor Sarah Flack (who has subjected the quicksilver, time-shifting work of Bob Fosse’s regular editor Alan Heim to an acolyte’s scrutiny, then applied them to a series of films by Sofia Coppola). Legend has it that the film was originally intended as a more straightforward, linear revenge thriller until Soderbergh decided to try to spice it up by playing around with time (something he’d done on other films, notably “sex, lies and videotape,” “The Underneath” and “Out of Sight“).

This is by no means a new way to tell a crime/revenge story; the clear antecedent is John Boorman’s “Point Blank” (1967), whose hero’s stony-faced determination to get the money he’s owed finds a humanistic equivalent in Wilson’s insistent questions about what happened to his daughter, Jenny (Melissa George, seen only in flashbacks and photographs), who took up with a charming but spineless and mob-connected record producer, Terry Valentine (Peter Fonda). The hero hooks up with Jenny’s old acting class buddy, “Eddie” Roe (Luis Guzman), and her teacher and confidant, Elaine (Lesley Anne Warren), and tries to get to the bottom of what he believes to be a conspiracy. He somehow just knows that Jenny didn’t die on twisty Mulholland Drive while racing away from Valentine’s cliffside bachelor pad, a modernist outpost of tasteful showbiz wealth with a pool that seems to jut over a canyon. (“What are we standing on?” Wilson asks Eddie. “Trust,” he replies.) When Jenny died, Wilson felt a tremor while walking through a prison yard on the other side of the Atlantic. Now he seems to want not just to avenge Jenny, but to redeem himself for being a selfish, inattentive absentee father to a girl who lost her mother at a young age. He seems also to want to take stock in his whole life, including his promising and carefree youth, which is represented by soft, grainy “flashbacks” to Ken Loach’s 1970 drama “Poor Cow,” about a petty criminal who happened to be named Wilson. (Is “The Limey” the most surprising and delightful and entirely unexpected “sequel” in cinema history, or only top five? Discuss.)

As the film unreels, we seem to situate ourselves dead-center in Wilson’s consciousness. It’s remarkable how eloquently Soderbergh and Flack use multiple, redundant angles and slow-motion inserts and deliberately asynchronous images of people’s faces (backed by dialogue from some other take) to suggest the gap between how Wilson is seen by others (or imagines himself to be seen by others) and how he feels on the inside. At certain points the film’s editing evokes that of Oliver Stone’s 1995 stealth masterpiece “Nixon,” which would cut from a closeup of the grinning, hale, trying-too-hard president to an over-saturated or overexposed closeup of Nixon sweating or looking around furtively, sweat forming on his brow or lip: cinema as lie-detector test.

I’ve had many conversations over the years with “Limey”-heads (over whether the entire film is from Wilson’s perspective or if it’s mainly Soderbergh imagining the lives of these characters—and if it is mainly or entirely Wilson’s POV, how reliable that is, and whether he’s imagining the whole thing during the plane ride over or recalling it on the plane ride home (I vote for the latter, because of a cut to Wilson smiling on a plane, seemingly at the memory of Eduardo’s hangdog face). I’ve also heard the theory advanced that while “The Limey” is probably mainly taking place inside Wilson’s memory-strewn imagination (a place that includes piercing 16mm streak-y flashbacks to Jenny as a child seeming to stare at her criminal father in judgment) it sometimes jumps into other characters’ perspectives, as a third person omniscient novel might. This might account for the moments when we break away from Wilson and spend time with Valentine and his fixer Jim Avery (Barry Newman, exuding smooth menace) or with a couple of vicious and prideful but barely competent hitmen (Nicky Katt and Joe Dallesandro), or with Elaine, who is introduced in a supermarket with the only closeups in the movie that feel reductive and condescending: sad single lady items being passed over a scanner, including waxing strips and frozen yogurt.

Among the film’s more strangely exhilarating scenes are the ones where Wilson and Elaine walk and talk about their respective memories of Jenny. Soderbergh splices together footage of the characters telling the same stories (or speaking the same lines) in different locations, so that the talk is continuous but the images seem intriguingly indecisive. Whether Soderbergh and Flack were merely having fun with all the “coverage” that cinematographer Ed Lachman collected or pursuing a purposeful narrative strategy, the effect is remarkable, more akin to supple and intuitive literary fiction than any other commercially viable crime thriller you can name. It’s as if Wilson can remember the gist of what was said, but can’t decide where it was said. At the dock? At the restaurant? At Elaine’s apartment? Somewhere else?

We also see Wilson envisioning scenarios that don’t actually play out. Many are violent: he’s making an honest effort to think before he acts these days. We also see him envisioning what sort of relationship Jenny had with Terry—a relationship, as it turns out, that had overtones of paternal longing; Jenny’s love couldn’t save her criminal father, and so she grew up and found a fatherly criminal to love.

To my knowledge, has seriously investigated this aspect of Soderbergh’s movies—the idea of fate or destiny or The Universe driving human affairs (and the related question of whether there is free will or if we’re all living a dream)—but should anyone choose to do so, “The Limey” would be a great starting place. It evokes a key image from Kurt Vonnegut’s psychodrama “Slaughterhouse Five,” in which aliens who exist outside linear time can look at all of creation as a fixed and finished geographical object, like a map of a mountain range, and point to it and say, Look, here is where Wilson flirted with Elaine for the first time, and there’s where he killed several men in a warehouse with a hidden gun and screamed “Tell him I’m coming!”, and there’s where Terry broke his ankle, and there’s where little Jenny shamed her father and tried to stop him from becoming the father he eventually became and perhaps was foretold or doomed to become, and who would eventually be consumed with remorse over how little time he actually spent with her and how little he cared about himself, and then translate that regret into rage, turning depression outward, only to come to a kind of merciful self-awareness near the end of the tale, then settle into the more difficult task of sifting through his memories, making sense of them, and here we are, the plane is touching down at LAX and they call me the Seeker.