Steven Soderbergh’s “The Underneath” takes the bones of a 1949 noir classic named “Criss Cross” and drapes them with modern characters so neurotic that crime almost seems like therapy: It keeps them occupied. It’s not every thief who reads Self-Esteem: A User’s Guide, especially when self-esteem is the one thing he has more of than he can possibly justify.

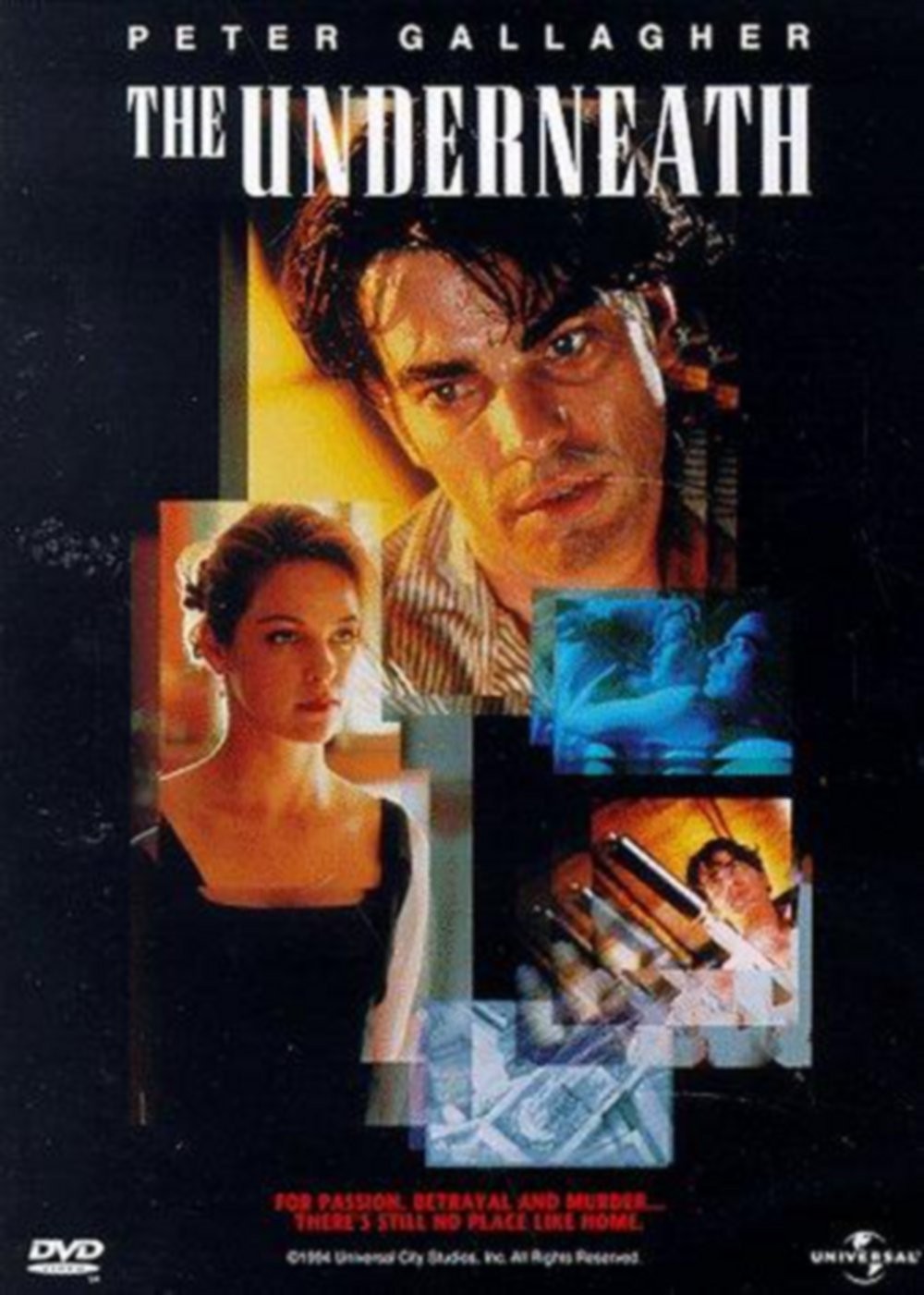

The character reading the book is Michael (Peter Gallagher), who has returned home to Austin, Texas, for the wedding of his 56-year-old mother to a genial man (Paul Dooley) who works for an armored-car company. People in Austin are surprised to see him, especially his wife Rachel (Alison Elliott), who is still furious at him for walking out on her. He walked out on a lot of other people, too, including some heavy-duty bookmakers he owed big bucks to.

“I’ve squared with everybody,” he tells her. “Except me,” she says.

The early passages of the plot, which are the most intriguing, play more like Soderbergh’s “sex, lies . . . and videotape” than like the Burt Lancaster thriller. Although there are flash-forwards to what looks like a crime in the making, most of the drama involves Michael’s uneasy relationship with his brother David (Adam Trese), a cop who despises his weaknesses. There is also the problem of Tommy Dundee (William Fichtner), the explosively jealous night-club owner who is Rachel’s current lover.

At first we can’t see where the plot is headed, although in the movies it’s a good bet that when anybody goes to work for an armored car company, sooner or later there is going to be an armored car robbery. Michael hangs around Tommy Dundee’s bar for glimpses of Rachel, who still seems to have feelings for him. And in flashbacks we see why they broke up: He was a compulsive gambler who bet money he didn’t have on sports events, and spent his winnings on a 16-foot satellite dish so he could better see the televised games. (“Is that thing safe?” Alison asks the satellite installer. “Yes, ma’am, it’s safe. Just don’t stand in front of it.”) Rachel herself is a young woman without a game plan. She wants to be an actress, but is happy to start out with “exposure,” and paints numbers on fresh eggs so she can rehearse the way the girls read the numbers off the ping-pong balls during the lottery drawings. Michael, meanwhile, gambles his way into debt, convinced he will start winning: “I don’t have a system; I just know.” It would be unfair to the plot to describe much more of it – although, for that matter, the plot is also a little unfair to us.

There is about one twist too many for my taste; I like to be fooled but I don’t like to be toyed with. By the end of the film the 1949 film noir sources are plainly in view, but earlier, Soderbergh seems more interested in personality quirks than double-crosses, and those are the more interesting scenes, as we begin to understand just how unreliable Michael is.

Why did Soderbergh want to remake an old film noir, anyway? Take out the crime elements and flesh out the human elements here, and you have a more interesting movie, I think. I was intrigued by the Rachel character, who is attracted to unreliable men, and likes to jump back and forth between the frying pan and the fire. And there are interesting shadows in the family history of the widowed mother and her two boys who hate one another (“I can’t believe,” the cop tells Michael, “that you’d wear our father’s suit to our mother’s wedding”). Funny how the melodrama, when it comes, is less entertaining than the real drama Soderbergh seems so wary of.